Eclipse chasers are no different. For them, the perfect solar eclipse combines a crystal-clear sky with several minutes of totality. Add an exotic locale to the equation and you’ll pique the interest of any shadow chaser. And though perfection can be hard to achieve, the solar eclipse of July 2, 2019, comes close, offering a great opportunity to turn this dream into reality.

The path of totality begins in the South Pacific, some 1,200 miles (1,900 kilometers) east of New Zealand’s North Island. That’s where the New Moon first covers the Sun’s entire disk. As the dark inner part of the lunar shadow, called the umbra, heads east across the Pacific, it makes landfall only once. This spot is Oeno Island, an uninhabited coral atoll in the Pitcairn Islands. Totality there lasts 2 minutes 53 seconds. Maximum eclipse occurs about 670 miles (1,080 km) north of Easter Island, where shipboard passengers could experience 4 minutes 33 seconds of darkness at midday.

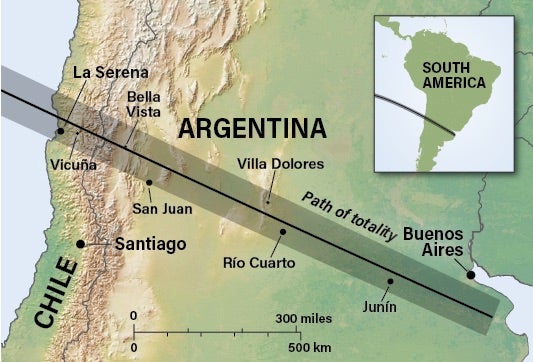

As the Moon’s shadow presses eastward, the length of totality dwindles slowly. It drops to 2 minutes 36 seconds on the center line by the time the umbra touches the coast of Chile in late afternoon. In the beautiful port city of La Serena, some 30 miles (50 km) to the south, eclipse viewers will witness 19 fewer seconds of totality. The track then heads east through Chile, crosses the Andes Mountains, and traverses Argentina. The total eclipse ends at sunset in the suburbs south of Buenos Aires, where observers can see a little more than two minutes of totality.

Weather prospects look promising across much of the path’s South American trek. There’s a reason why professional astronomers have built four major observatories — Cerro Pachón, Cerro Tololo, La Silla, and Las Campanas — in the foothills of the Chilean Andes, and the first three lie within the path. Be aware that travel restrictions will be in place at these sites July 2, though many eclipse travelers will visit the large telescopes in the days before and after the eclipse.

And while the weather during the Southern Hemisphere winter is not the greatest, it’s still pretty good. The best prospects in Chile appear to be away from the coast in the Elqui Valley, perhaps near the town of Vicuña. The high peaks of the Andes are magnets for clouds, but they also wring out Pacific moisture and make the eastern slopes in Argentina excellent sites. The town of Bella Vista lies just off the center line and should be a superb spot for eclipse viewing. But wherever you plan to set up, if you stay mobile and alert to the forecast, you should be able to find clear skies.

On the big day

To get the most from viewing a total solar eclipse, plan to arrive at your site an hour or more before first contact, when the Moon first touches the Sun’s disk. This will give you plenty of time to set up equipment. A word to the wise: If this is your first total eclipse, keep it simple. Don’t try to photograph the eclipse. The few minutes of totality will fly by, and you don’t want to spend them fiddling with your camera. If you find the experience exhilarating, you’ll likely be back for more. That’s when you can attempt imaging.

If you want to view the eclipse through binoculars or a telescope, place the filter over the front end of your optical system. And be sure to keep the lens cap on any finder scope — curious people might otherwise be tempted to look through the finder without realizing the danger.

First contact

The eclipse gets underway when the Moon’s limb initially touches the Sun’s disk. Although first contact is technically invisible — the Moon has yet to block any of our star — sharp-eyed observers will notice a tiny bite within a minute or two. From Chile and Argentina, this notch appears at the Sun’s lower left edge.

The next 30 minutes will seem to take hours. Most people won’t notice the subtle changes to their surroundings. The sky slowly grows darker, but your pupils dilate to compensate for the lower light levels. An occasional glance at the Sun through your eclipse glasses will reassure you that events are on track. It’s also fun to watch our satellite’s dark limb overtake individual sunspots through a properly filtered telescope.

Once the Moon blocks more than half our star, changes become more obvious. Colors seem more intense. Shadows grow sharper as the source of light in the sky shrinks. And temperatures start to drop, slowly at first, but then more quickly. The chill is more noticeable when humidity levels are low.

The Moon’s relentless march soon reduces the Sun to a crescent. In a cruel form of cosmic payback, time now seems to speed up. But take some deep breaths and explore your environment. Look on the ground beneath a leafy tree or bush. The tiny gaps between the leaves often project hundreds of images of the crescent Sun. Wildlife interprets the growing darkness as a sign of nightfall, and birds come home to roost. Farm animals start to head back to their barns.

In the final few minutes before totality, the solar crescent dwindles to a thin sliver. Then the last bright part of the Sun’s disk becomes visible — the glorious diamond ring. As it fades, valleys along the Moon’s limb allow tiny points of light to poke through. Known as Baily’s beads, this string of pearls shrinks in number as the Moon continues its inexorable advance.

Totality arrives at second contact, when the Moon extinguishes the final bead. Now is the time to remove solar filters from your eyes, binoculars, and telescope. Examine the totally eclipsed Sun with whatever equipment you have — there’s no risk to your eyes with the solar disk completely covered.

As your eyes adjust to the sudden darkness, the Sun’s corona takes center stage. The corona’s ghostly glow appears pearly white and likely will extend for a few solar diameters. Watch for delicate loops, swirls, and streamers. The corona’s size and shape vary from one eclipse to the next. With solar activity now at its lowest level in years, the corona should appear asymmetric and show lots of streamers.

Also watch for reddish prominences arching above the Moon’s limb. These fiery tongues of glowing hydrogen are anchored to the Sun’s surface and extend into the corona. You’re most likely to see them shortly after totality starts and shortly before it ends; at mideclipse, the Moon may well block them from view. Binoculars will help you see them better.

This all happens at breakneck speed. If it doesn’t seem too much of a blur, though, consider taking a few seconds to explore the rest of the sky. Notice the sky’s color and the twilight hues that ring the horizon. You also should see the brightest planets and maybe a star or two. From Chile, Venus will blaze below the eclipsed Sun while slightly fainter Jupiter will stand on the sky’s opposite side. Sirius — the sky’s brightest star with the Sun concealed — will shine more than a third of the way up in the west. And Canopus, the next-brightest star, appears at nearly the same altitude in the southwest.

After totality, the partial phases play out in reverse. Although the main show has ended, there’s still plenty to enjoy. This is a great time to view things you might have missed before totality. Pay closer attention to sharp-edged shadows and crescents projected onto the ground.

As the partial eclipse winds down, talk inevitably turns to the next chance to experience totality. The wait won’t be long. On December 14, 2020, the Moon will completely block the Sun along a path that coincidentally crosses Chile and Argentina again. The track lies farther south, and totality won’t last quite as long. Still, those positioned on the center line will witness more than two minutes of darkness, and that sounds pretty good to me.