In this brief guide, I want to remove the intimidation of this constellation’s size and provide a list of the best objects to point your scope at. I list them in order of increasing right ascension. That means the westernmost objects come first and, as you observe, the latter ones rise higher in the sky.

Please note that I don’t include any elliptical galaxies in this story. They’re still plotted on the map you’ll find on the following paragraphs, but I describe the best of them in “The sky’s best elliptical galaxies.”

A crowded field

Our first object is the Silver Streak Galaxy (NGC 4216). It lies at the western edge of the Coma-Virgo Cluster of galaxies. From a dark site, a 10-inch telescope will reveal several hundred galaxies here, so take your time and be sure of your identification.

NGC 4216 appears as a magnitude 10 streak of light nearly five times as long as it is wide (7.8′ by 1.6′). The core is bright, but to see its bulge will require a 12-inch or larger scope. Look for 12th-magnitude NGC 4206 12′ to the southwest of NGC 4216. It has a similar appearance to its brighter neighbor.

The next target is M61, the first of four Messier objects on our list. It glows at magnitude 9.7 and measures 6.0′ by 5.9′. This is a face-on spiral galaxy; however, its arms wind tightly around the core, so it doesn’t look nearly as good as others of this type. That said, a 12-inch telescope will allow you to see the stubby extensions of two arms. Through really big scopes at high magnification, look for a thick bar that runs north-south through this object.

The core of this galaxy spans roughly one-third of its length. You’ll also notice that the halo region is more apparent than in similar spirals. An 8-inch telescope is a great instrument for viewing NGC 4429 at a dark site. Crank up the power past 250x to see all of its details.

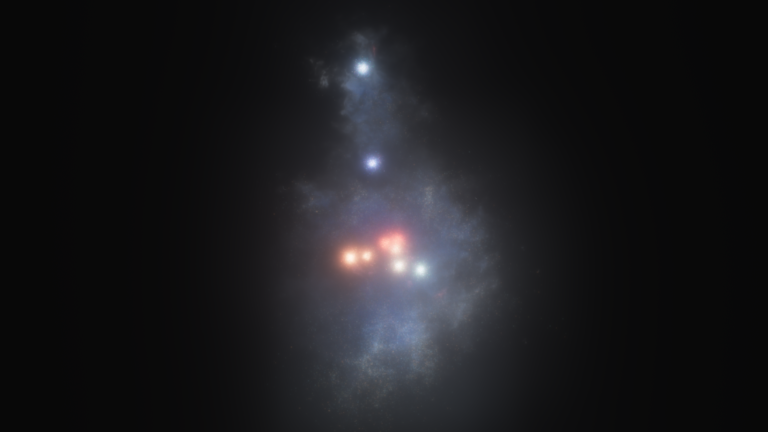

Less than 2° north of NGC 4429 you’ll find NGC 4435 and NGC 4438, a pair of galaxies called the Eyes. The two glow at magnitude 10.2 and 9.7, respectively, and they’re not small, spanning an area 8.5′ by 3′. Some millions of years ago, these star cities came within 16,000 light-years of each other. If you can view them through a 12-inch scope, try to spot the distorted outer regions of NGC 4438.

Oh, boy! Our second Messier object is next. Unfortunately, M90 may be one of the least interesting spiral galaxies you’ll ever observe. That’s too bad, because we tend to expect more from Messier objects. It glows reasonably bright for a galaxy, at magnitude 9.5. And it has some size, too, measuring 10.5′ by 4.4′.

What you’ll see is an object that measures two times as long as it is wide. M90’s spiral arms wind tightly around it, however, so unless your scope’s mirror measures 2 feet across, be content to just check this bright galaxy off your list and move on.

South and east

The fourth and final Messier object on our list, the Sombrero Galaxy (M104), is anything but a disappointment. This spiral glows at magnitude 8.0 and measures 7.1′ by 4.4′. It’s a great object to show off through a medium-sized scope, but do wait until it stands highest in the south.

M104 was the first galaxy for which astronomers detected a large redshift. Redshift measures the speed of an object away from us, caused by the universe’s expansion. In 1912, American astronomer Vesto M. Slipher discovered that the Sombrero Galaxy was moving away from us at a speed of 2.2 million mph (3.6 million km/h).

M104’s lens shape and the dark dust lane that splits it are easy to spot. The galaxy’s two sections have unequal brightnesses — the north outshines the south because M104 inclines 6° to our line of sight. The dust lane, therefore, appears to cross south of center.

Through a 4-inch telescope, you may detect the dust lane only near the Sombrero’s center. The core is bright and a large halo surrounds it, extending above and below the sections of the spiral arms nearest the nucleus.

Next up, NGC 4731, is not a bright galaxy (magnitude 11.5) but it has several features I think you’ll find worth your observing time. It appears as a highly distorted S shape because it doesn’t travel through space alone. You’ll easily spot its brighter companion: Look only 0.8° to the northwest for magnitude 9.2 NGC 4697, an elliptical galaxy I describe on page 61. Gravitational interaction between these two has nearly destroyed NGC 4731’s spiral arms.

Through a 10-inch telescope, observe NGC 4731’s long, relatively bright central bar. If your observing site is dark, crank up the power past 200x and look at the wide, irregular spiral arms that originate from each side of the bar.

The western arm appears somewhat brighter. Tiny bright patches within both arms signal hotspots of star formation. Through a 20-inch or larger telescope, use a nebula filter to increase the contrast of those regions and the galaxy’s older stars.

If you want to show someone an edge-on galaxy, the next object on our list will do nicely. Barred spiral NGC 4762 glows at magnitude 10.3. More than four times as long as it is wide (9.1′ by 2.2′), NGC 4762 appears as a white line through medium-sized telescopes.

You won’t see a central bulge through any size scope. All you will notice is that the core appears ever-so-slightly brighter than the arms.

Next up is NGC 4856, a magnitude 10.4 spiral that lies near Virgo’s western border with Corvus. Through an 8-inch telescope at 200x, you’ll see a disk with a small, bright central region. The galaxy stretches more than three times as long as it is wide (4.3′ by 1.2′) in a northeast-to-southwest orientation. For those of you using 14-inch or larger scopes, crank the power past 350x and look for a magnitude 13.1 foreground star just barely east of the core.

At magnitude 13.9, you might be inclined to skip the next target, planetary nebula IC 972, for less difficult fare. That’s fine if you’re viewing through a 4-inch scope, but if you have a 10-inch or larger instrument, have a look at the faint outer layers of this once Sun-like star. Because of its small size (43″), IC 972 has a reasonable surface brightness. Better known as Abell 37, this object appears uniformly illuminated with a sharp edge.

Point a 4-inch telescope at it, and you’ll see lots of faint stars and one bright orange one — magnitude 8.0 SAO 139967, which sits a bit more than 1′ east-southeast of the cluster’s center. The star isn’t part of NGC 5634, it just happens to lie in the same direction from our viewpoint.

The cluster’s stars are condensed, meaning you won’t easily resolve them into individual points. But the back-and-forth visibility battle you’ll encounter between the star and the cluster makes for a fascinating observation.

As you’ve probably inferred, there are a great many more targets in Virgo. The ones on this list, however, should keep your scope pointed in this constellation’s direction for a full night. Take your time, sit comfortably as you observe, and enjoy the view.