Key Takeaways:

- The 30 Doradus Nebula in the Large Magellanic Cloud hosts thousands of igniting stars, including many exceptionally massive stars within the R136 cluster, some exceeding 100 solar masses.

- Star formation requires gas, dust, gravity, and turbulent events. Interstellar clouds, composed primarily of hydrogen and helium, contain numerous molecules and become sites of star formation when triggered by events such as supernova shockwaves.

- Stars evolve through various stages, including protostar, T Tauri star, and main sequence star phases. Their lifetimes depend on mass, ranging from billions of years for low-mass stars to millions for high-mass stars.

- Massive stars end their lives in supernovae, producing neutron stars or black holes and enriching the interstellar medium with heavy elements, providing material for future generations of stars. Type Ia supernovae, resulting from the collapse of white dwarfs exceeding the Chandrasekhar limit, are used as standard candles for cosmological distance measurements.

Stellar building blocks

To forge a star you need gas, dust, gravity, and violent stirring. From a dark location in northern summer and fall, an observer can see the Milky Way cascading in its turbulent passage out of Cygnus through Aquila, Sagittarius, and south toward the Southern Cross. Its glow is the combined light of the billions of stars in our galaxy’s disk. Optical and radio observations show that gas is plentiful, and myriad opaque patches without apparent stars reveal that dust is pervasive.

The dust consists of microscopic mineral grains made of silicon, magnesium, iron, and many other metals, as well as carbon in its varied forms. On average, our galaxy’s disk contains just one grain per cubic meter. But there are a lot of cubic meters between stars, so, overall, dust constitutes roughly 1 percent of the total mass of interstellar matter.

While interstellar dust may be thinly spread, it also tends to clump together, even forming dense clouds. Some of these clouds are so thick that the Incas of South America made them into constellations. Among the closest are the Taurus-Auriga clouds, which are only a thousand light-years away, allowing us to study them in great detail.

Opaque clouds of interstellar dust keep out heat radiated by nearby stars, and the gas within the dark clouds falls nearly to absolute zero. The gas has a chemical composition of 90 percent hydrogen and 10 percent helium — roughly similar to the Sun — and at these low temperatures, we would expect little chemical activity.

To the contrary, we find through radio emissions that the clouds are filled with molecules. More than 200 molecular species are present, dominated by molecular hydrogen (H2), but we also observe carbon monoxide (CO, which is used as a tracer for the hard-to-observe hydrogen), carbon dioxide (CO2), methyl alcohol (CH3OH), ethyl alcohol (CH3CH2OH), and possibly even complex molecules such as urea (CH4N2O) and others important to life. Some molecules that do not exist on Earth abound in space, while many molecules responsible for the emissions we see remain unidentified.

The real showpieces are the gaseous, dusty diffuse nebulae. These occur where the interstellar clouds lie in close proximity to hot stars with temperatures more than 26,000 kelvins or so. The ultraviolet radiation given off by these stars can destroy molecules, ionizing (removing electrons from) the interstellar gas, which causes it to glow. With just binoculars, you can see the vast Orion Nebula (M42) in the Hunter’s sword, as well as many other such nebulae. Telescopes reveal jaw-dropping beauty.

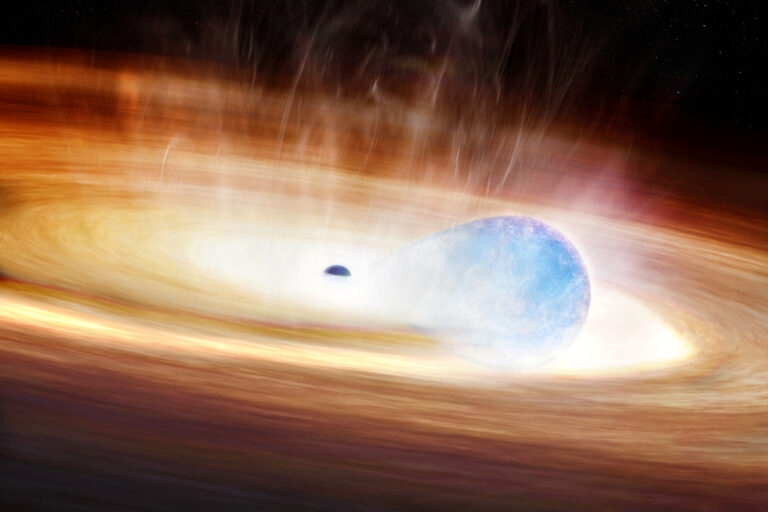

Named after their faint prototype, slightly older T Tauri stars appear highly variable as they sporadically gain mass, accreting it from a disk of material swirling around their equator. At the same time, these stars lose mass via powerful jets emerging from their poles. Amazingly, this disk/jet structure shows up not just in growing stars, but also in stars that are ejecting their outer envelopes as they prepare for death, in star systems where mass is being transferred from one to the other, and even around the supermassive black holes residing in galactic cores.

While the clouds are filled with T Tauri stars, none of these stars is visible to the naked eye. Moving outward perpendicular to the disk, the jets hammer the surrounding interstellar gas into bright shock waves, which are common phenomena both on Earth and in the universe in general. A shock wave is formed in a fluid when a body moves faster than the natural speed of the wave within it, as with the bow-wave off the prow of a speedboat. Here, this violent meeting results in glowing nebulae called Herbig-Haro (HH) objects, which occur where the jets are brought to a halt by the interstellar gasses. New stars appear as a pair of HH objects connected by jets from the star in the middle. Four and a half billion years ago, the Sun would have looked like this. In many cases, we see only a single jet with or without its star, as various portions of the structure can be hidden by local dust clouds.

Multitudes of stars are often created at roughly the same time, and their mutual gravity binds them into an open cluster with a large range of masses, like the Pleiades (M45), the Hyades, or the Beehive (M44). These clusters slowly evaporate, their constituents dispersing with time. We believe our Sun may have been born into one such cluster.

Additionally, much of this action takes place within the larger dark clouds and is invisible until stellar radiation and winds dissipate the parent dust clouds. When the Sun was born, only a few other stars might have been visible from its location because of the dust in the local birth cloud.

Main sequence dwarfs

Once formed, the star remains stable as it consumes its hydrogen fuel. Seventy percent of the Sun’s nuclear energy is supplied by the proton-proton (pp) chain, whereby four protons join in a three-step process to make helium, with the ejection of protons, gamma rays, and neutrinos (near-massless particles that carry energy at nearly the speed of light). The other 30 percent comes from the carbon cycle, in which carbon and hydrogen combine to create a chain of six reactions that generate nitrogen, oxygen, and ultimately ends with carbon and helium, the former of which allows the cycle to begin again. This also produces gamma rays and neutrinos, as well as positrons (positively charged electrons).

Because our star is so dense, the heat from the gamma radiation takes hundreds of thousands of years to work its way out of the Sun. By contrast, the neutrinos — unhindered by frequent interactions with other atoms — leave directly. Neutrino detectors allow us to look at the Sun’s core and show that our theories are correct. Trillions of them pass through you every second and you don’t feel a thing.

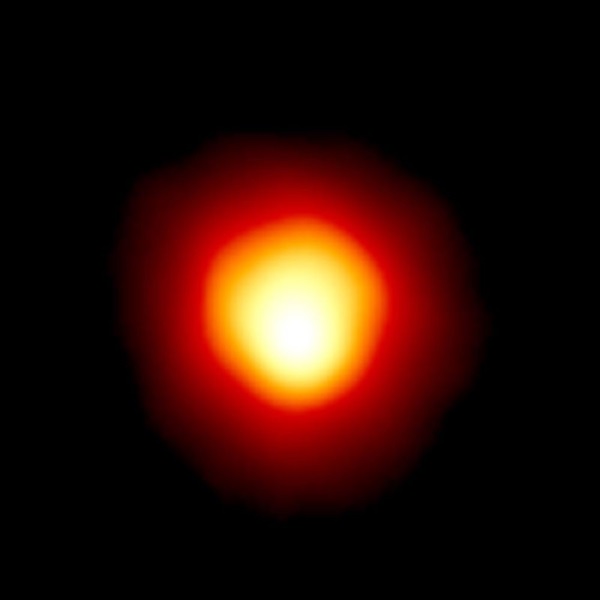

The range of masses of hydrogenfusing stars — called main sequence stars to differentiate them from stars that are dying — runs from 0.075 to over 120 solar masses. For historical reasons, all of these ordinary stars are called dwarfs, but don’t let the term fool you. The comparatively modest Sun — a yellow dwarf — is about 864,000 miles (almost 1.4 million kilometers) across, while the most massive dwarfs are many times that. On the other hand, the coolest red dwarfs are not much bigger than Jupiter.

There may be only a few monster stars in a galaxy, while dim red dwarfs constitute up to 70 percent of the local stella population. Below 0.075 solar mass, stellar cores are so cool that the pp chain won’t work, resulting in a brown dwarf that is still capable of fusing its natural deuterium (hydrogen atoms with both a proton and a neutron in the nucleus) down to a mass of 1.2 percent the Sun’s mass, or 13 Jupiters. However, we’ve found planets around other stars heavier than that, blurring the line between stars and planets and leaving open key questions about how the two are formed.

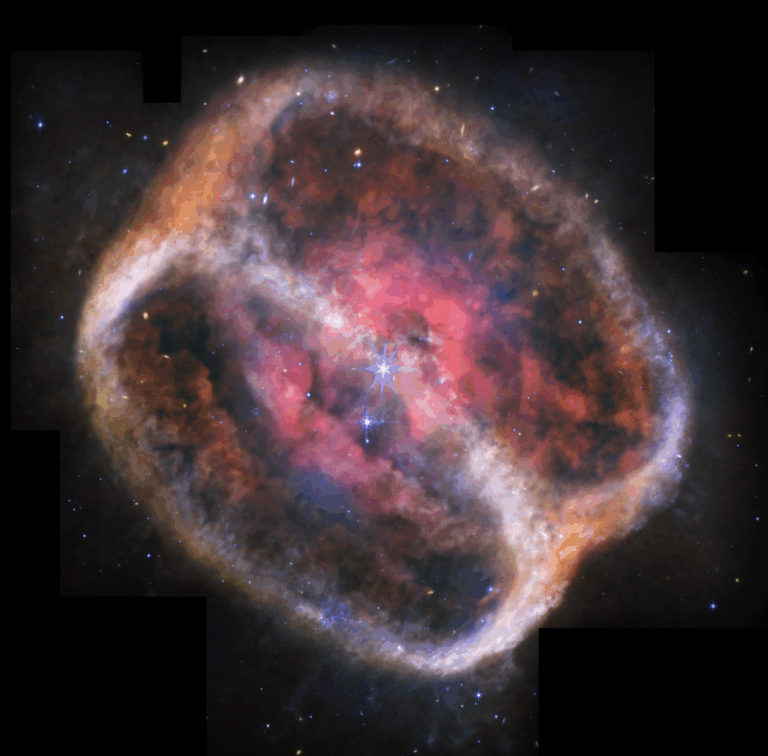

NGC 6543 are planetary nebulae that develop as Sun-like stars slough off their outer layers in the later stages of their lives. When light from the dying star at the center of the debris field hits this gas and dust, the material glows, creating ethereal shapes. Planetary nebulae ultimately fade over tens of thousands of years, as the central star becomes a white dwarf and slowly starts to cool.

Fusion rates climb so rapidly with increasing mass and core temperature that the lifetimes of stars actually decrease as mass increases. They run from the age of the galaxy — some 13 billion years — for the least massive stars to just a few million years for the most massive. In the middle, the Sun has a hydrogen-burning lifetime of about 10 billion years, of which 5 billion are history.

Twice a giant

While details differ, the end products of stars in the midrange of stellar masses are similar. In 5 billion years, the Sun will have converted its internal hydrogen to helium and the central nuclear fire will go out. No longer supported by the energy of fusion, the helium core will shrink, as a thin shell of fusing hydrogen surrounds it. Squeezing down under gravity’s relentless fist, the core will also heat, causing the star’s outer envelope to expand and cool as the star brightens to become a giant.

When the core hits 100 million kelvins, the helium nuclei that had been made earlier fuse into carbon, which requires that three helium atoms hit each other simultaneously. The new helium burning, plus the old hydrogen fusion in the surrounding shell, once again stabilize the star against collapse. In the core, when the newly made carbon is hit with yet another helium nucleus, it makes oxygen.

Externally, the giant grows even bigger and brighter, perhaps becoming as big as the inner solar system, radiating with the light of thousands of Suns. Atoms heavier than the iron given to the star at birth begin to capture neutrons that decay into protons, making yet heavier elements as the star begins to fill in much of the chemist’s periodic table.

As the second phase of brightening proceeds, winds blow ever stronger from the stellar surface. The Sun will lose half its mass this way, bigger stars losing much more, as they expose their hot inner cores. No longer supported by nuclear burning, the cores are held up by free electrons through a quantum process called degeneracy, which makes them incompressible.

For a few tens of thousands of years, the exposed core remains hot enough to light up the shells of matter that it had previously ejected. The system becomes a strikingly beautiful expanding planetary nebula, while the inner core becomes a white dwarf made of carbon and oxygen with a density of a million grams per cubic centimeter (the equivalent of compressing 2,204 pounds [1,000 kilograms] into a space the size of a sugar cube). The star’s old outer envelope — rich in heavy chemical elements as well as carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen — flees into space, leaving the still-glowing white dwarf behind. The rate at which white dwarfs cool is so slow that every white dwarf ever made since the beginning of the universe is still hot enough to be visible.

Go out with a bang

In a star of greater mass, hydrogen and helium fusion proceed as before. But with the extra mass, the chain can go further. Carbon and oxygen fuse to a mix that includes neon and magnesium, which then goes on to fuse to silicon and sulfur before reaching iron. Each time the core initiates a new kind of fusion, it is surrounded by shells running the previous reactions. Fusion reactions that create nuclei on the periodic table up to iron generate energy. But above that limit, creation of new and heavier elements requires energy. Iron is the most tightfisted of all elements — it’s hard to break apart into its constituent protons and neutrons, which is why it is so common. Externally, the star grows enormously, becoming a supergiant. Such stars could enclose the orbit of Jupiter, even nearly that of Saturn.

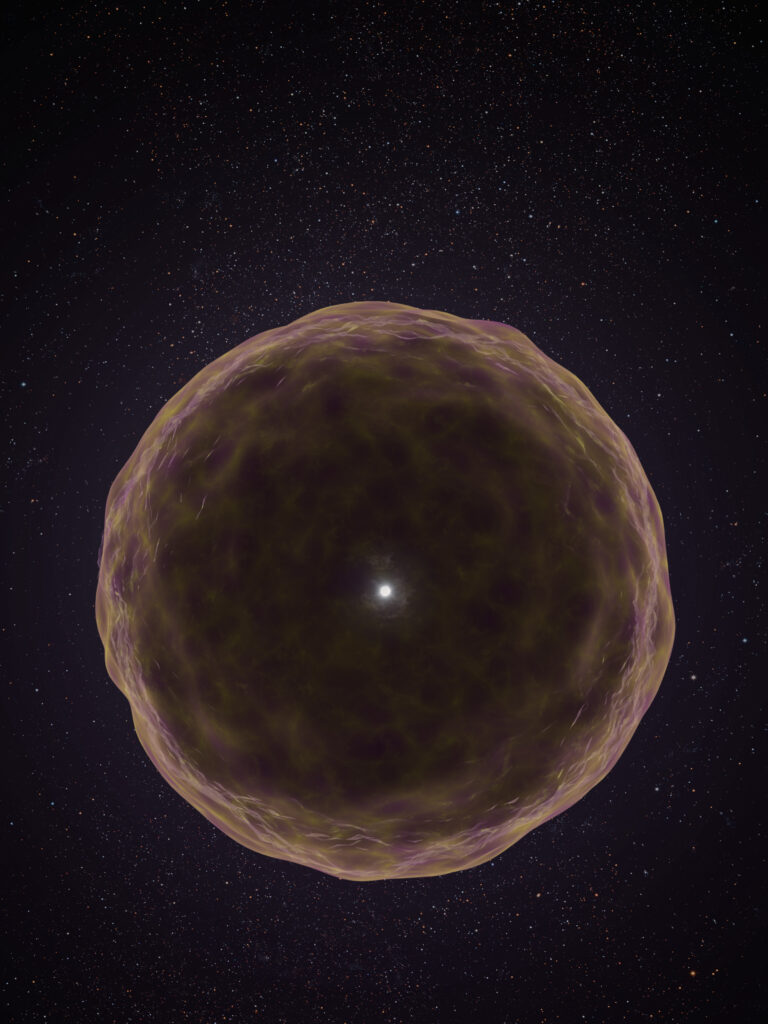

Around 1930, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar discovered that when a star’s core mass reaches about 1.4 solar masses, Einstein’s theory of relativity tells us that electron degeneracy can no longer support the star’s core. The whole mess comes crashing down, as everything (including the iron in the core that took so long for the star to make and much of the material in the enclosing shells) turns back into neutrons. We expect this to happen when the star’s initial mass exceeds about eight Suns.

The resulting neutron star has a diameter of about 12.4 miles (20 km, or about the size of Manhattan) and a density a million times that of a white dwarf. Upon its birth, the neutron star first overcompresses and then violently bounces back, sending a monstrous shock wave through what’s left of the star. This event blasts the material outward in a mighty type II supernova that sends the temperatures into the billions of kelvins and can be seen billions of light-years away.

Nuclear reactions run amok, but as the ruined star expands, it also cools. This freezes in a specific distribution of elements, including one-tenth of a solar mass of iron. Left behind might be a spinning, highly magnetic pulsar that appears to flash at every rotation. Or, if the star’s initial mass is high enough, a black hole will form with a gravitational pull so great that nothing, not even light, can escape.

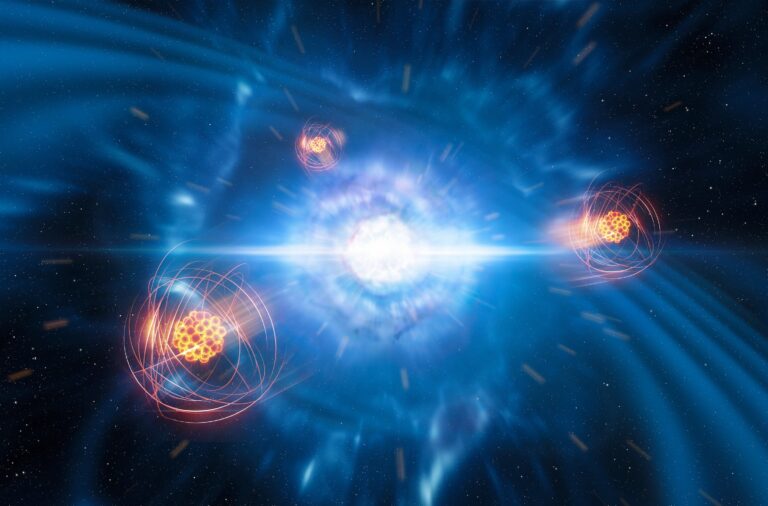

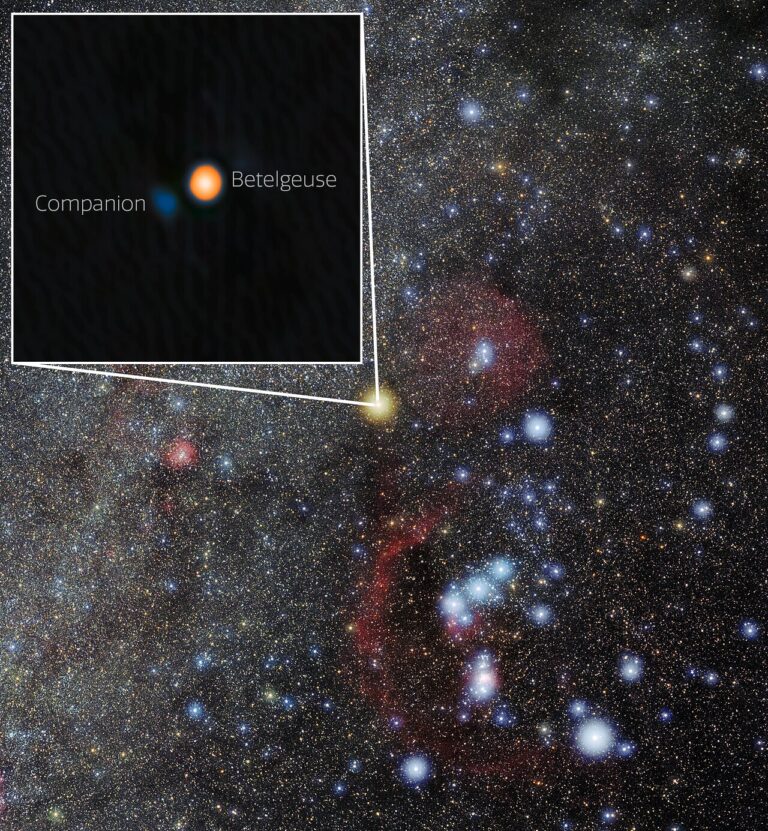

Double stars have their own tales to tell. A star in a binary system can pass some — even much — of its mass to a white dwarf companion. Alternatively, two mutually orbiting white dwarfs can merge. If the result in either case exceeds the Chandrasekhar limit of 1.4 solar masses, it will explode as a type Ia supernova — which is even brighter than the type II version and yields even more iron — as the stars annihilate themselves, leaving nothing behind.

Because they all occur at the Chandrasekhar limit, type Ia supernovae all have about the same maximum brightness. So, by measuring how bright they appear, astronomers can easily determine the distance to these objects. They are so bright that astronomers can see them across the universe, and subsequently use them to measure the universe’s expansion rate by comparing how far an object is expected to be with its actual distance. The last two supernovae seen in our galaxy were Kepler’s Star in 1604 and Tycho’s Star in 1572. Both were type Ia. Before that was the type II Chinese “guest star” of 1054, whose violently expanding remnant, the Crab Nebula (M1), can be viewed with a small telescope. Hidden inside this remnant is the pulsar left behind by the massive progenitor.

But this is not the end of the story. The expanding supernova remnant, rich with heavy elements, including mass injected by the now-dead star’s giant and supergiant winds, finds its way back to the interstellar clouds. Its detritus becomes the material that will ultimately make new stars, thus completing the cycle.