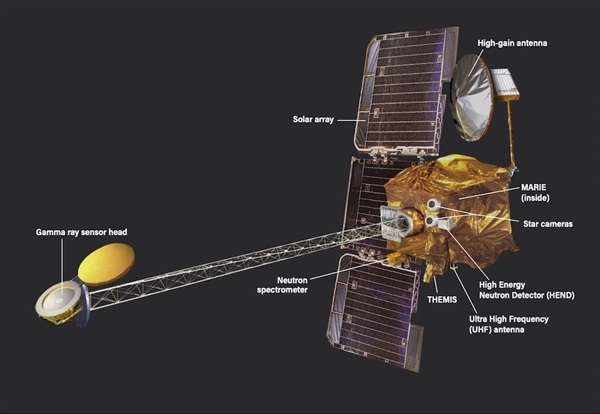

Twenty years of wear and tear have undoubtedly taken their toll on the plucky robotic craft. In fact, a series of strong solar flares put one instrument out of commission in 2003, just a few years after blasting off for the Red Planet. And, in 2012, the spacecraft lost one of four reaction wheels, which are responsible for controlling its orientation (though the three remaining wheels continue to function).

But “Odyssey is remarkably healthy,” says Phil Christensen, the principal investigator for Odyssey’s Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) and a geologist at Arizona State University. “It’s just this crazy workhorse spacecraft that rarely goes into safe mode.”

Two decades of science

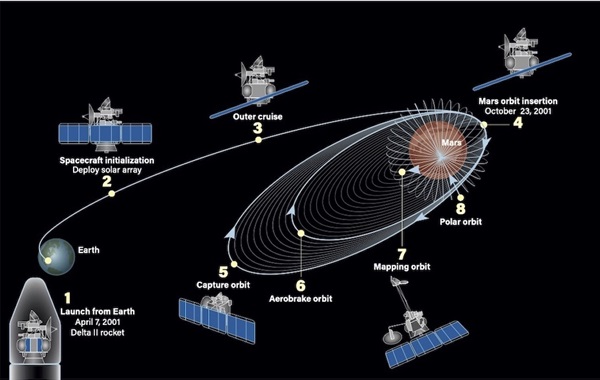

Odyssey arrived at Mars on October 24, 2001, with the goal of investigating the martian environment. The spacecraft was designed to map the planet’s chemical and mineralogical makeup as a step toward understanding the role water played in shaping the environment, both past and present. The orbiter completed its primary mission in August 2004, then began to take on a series of two-year mission extensions, each dedicated to a specific set of objectives.

“Odyssey has played a pivotal role in changing how we think about Mars,” says Lori Glaze, NASA’s Planetary Science Division director. “It has really changed our perception of a planet that [we thought] was a dry desert to one that’s a frozen desert.”

Although Odyssey made an initial splash by finding signs of ice beneath Mars’ surface, it didn’t stop there; the craft also uncovered snowpacks in some of the planet’s warmer regions. These snowpacks, potentially remnants from a martian ice age, provided some of the first hints that Mars is experiencing ongoing climate change.

“There’s a lot of ice on Mars,” Christensen says, pointing out that in some places it can lie as deep as 10 inches (25 centimeters) beneath the surface. “That’s going to be extremely important when we send humans to Mars, using that water ice.” Mining ice could potentially provide the liquid water that humans need to survive, without having to lug it from Earth.

This potential for in situ resource utilization — using what materials are locally available — is an important factor in selecting future human landing sites on Mars. A 2019 paper published in Geophysical Research Letters used data from Odyssey and its sister craft, the Mars Research Orbiter, to look for ice that could easily be dug up by intrepid human explorers. “You wouldn’t need a backhoe to dig up this ice. You could use a shovel,” the paper’s lead author, Sylvain Piqueux of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), said in a press release. “We’re continuing to collect data on buried ice on Mars, zeroing in on the best places for astronauts to land.”

Odyssey’s extensive dataset also overlaps with weather data collected by NASA’s Mars Global Surveyor, and other orbiters have provided complimentary observations. “This allows us to look at the repeatability and the year-to-year variability in weather and climate,” says Odyssey’s project scientist, Jeff Plaut, a researcher at JPL. “The role of large dust storms is a focus of this research, and Odyssey acquired detailed observations of two of these global storms during its mission.”

One of Odyssey’s greatest achievements, however, was its comprehensive map of the Red Planet. In 2010, researchers combined some 21,000 THEMIS images to create the most accurate global map of Mars to date. According to Plaut, the map is now the starting point for almost all geologic studies undertaken on the Red Planet. “[THEMIS] gave us a very detailed view of the physical nature of the surface,” Christensen says. “That’s provided tremendous insight into the physical properties that are acting on Mars today.”

THEMIS also helped scientists find a collection of seven caves on the slope of the volcano Arisa Mons. These martian grottos likely formed due to natural underground stresses near the volcano. And while the caves are too high up to be much use for potential human habitats — or, for that matter, for hosting microbial life — they spurred the hunt for lower-altitude caves and lava tubes.

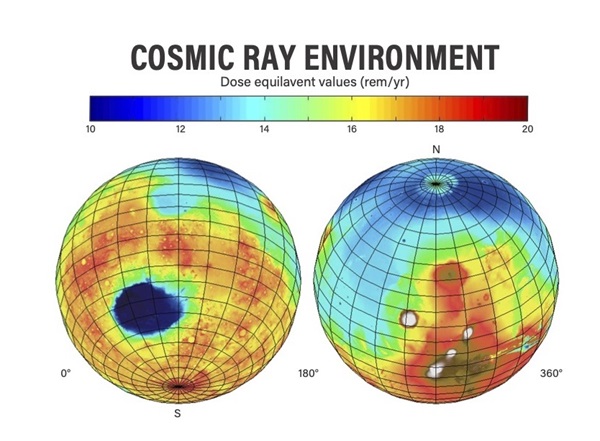

Although THEMIS has helped researchers to make great discoveries, mapping the martian surface isn’t a new job description. On the other hand, the now-defunct MARIE was the first experiment specifically sent to Mars to prepare for an eventual human presence. Unfortunately for future martians, MARIE found that radiation levels from solar flares and cosmic rays are two to three times higher on the Red Planet than on Earth. That’s because Earth is protected by our planet’s hardy magnetosphere and thick atmosphere, which Mars lacks. That’s not ideal, but it is vital environmental information to know.

With its 20-year anniversary on the horizon, the spacecraft is still far from finished with its science. “We have a number of ongoing science investigations, primarily with the THEMIS infrared and visible camera,” Plaut says. Those include observations of the martian atmosphere early in the morning and just after sunset, which could provide “unique information on the patterns of weather and climate that are not available to other orbiters,” he says.

Even now, scientists continue to publish studies that depend on Odyssey’s data, demonstrating its ongoing value. And as other missions arrive at the Red Planet, Odyssey remains in a position to help solve questions that have not yet been asked. Or, as Plaut says: “New discoveries continue to provide us with new targets.”

Rovers phone home

While Odyssey has pumped out a significant amount of science during its lifetime, it has also served as valuable support for other missions. Odyssey has helped researchers select the landing sites for the Opportunity rover, the InSight lander, and the Perseverance rover; plus, the orbiter provided confirmation that Curiosity had pulled off its unique sky crane landing maneuver. And in 2010, when the Phoenix Mars Lander suffered through a chilling martian winter it wasn’t designed to survive, Odyssey spent several periods of time listening for hints that the lander had come back to life following the return of springtime sunlight.

The end of the road?

Considering Odyssey’s ongoing productivity, it seems strange that it would be lacking in political support. Although government bean counters may point to the expense of keeping a 20-year-old spacecraft afloat, scientists say that the costs of maintaining it are miniscule compared to the science it returns. After all, the expensive and risky part — building and launching it to Mars at a cost of $218 million — is already done. “When you buy all the parts for a spacecraft, it’s worth a certain amount,” Christensen says. “When you assemble it, it’s worth more. When you get it tested, now it’s really starting to be really worth something. Then you launch and get it to Mars, and now it’s this priceless thing.”

“I think it’s silly to shut it off,” says Brian Hynek, a Mars scientist at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Hynek isn’t on the Odyssey team, but he uses the spacecraft’s data. “It’s still collecting great data, and it’s still working,” he stresses. Hynek points to the lunar seismometers placed on the Moon during the Apollo missions, which were shut down due to funding cuts.

“Now we’re trying to send people there and build settlements,” he says, “and not knowing the seismic history is a huge knowledge gap.”

That same thing could happen on Mars if Odyssey falls by the wayside. In addition to its ability to perform general science, Odyssey also has the only thermal infrared imager currently orbiting Mars. And THEMIS’ hundreds of thousands of images have significantly changed our understanding of the nearby Red Planet.

“There is no instrument right now on any other [martian] spacecraft or anything planned that has a thermal imager,” says Tanya Harrison, a planetary scientist who studies Mars and has often relied on Odyssey observations. “We wouldn’t be able to do any of the stuff we’re doing with THEMIS if we turned off Odyssey.”

Yet the mission remains on the chopping block.

Flipping the switch

Currently, Odyssey’s future remains nebulous, and President Trump’s proposed budget is just the first hurdle in a long race ahead. In July, the House of Representatives passed its Commerce-Justice-Science Funding Bill, which echoed the president’s numbers for NASA’s missions and left Odyssey at the shutdown level.

The next step is for the Senate to pass its own bill. But people familiar with the budget process say that’s unlikely to happen until after the 2020 presidential election in November — even though the new budget is supposed to kick off in October, the start of the 2021 fiscal year. After the passage of the Senate’s bill, the Senate and House of Representatives will come together to resolve their differences before voting on the newly drafted budget. Finally, after it passes, the president will sign the bill.

Right now, Odyssey doesn’t seem to have anyone advocating for it. NASA isn’t requesting an increased budget and no legislator seems particularly disturbed by the loss of the mission. It’s possible that a public groundswell of support could make a change, but the mission’s potential demise hasn’t attracted a lot of attention.

If nothing changes with Trump’s proposed budget — and Odyssey’s funding is slashed — mission controllers would likely have no choice but to permanently shut down the craft. However, the exact process for shutting down Odyssey isn’t publicly available, and Freedom of Information Act requests filed by Astronomy have been delayed, due, in part, to the COVID-19 pandemic. Still, Odyssey’s end has essentially been planned since launch.

“Whether it’s financial need to [shut down], or it reaches its end of [its] life, at some point, with a 20-year-old orbiter, you need to plan for these things,” Glaze says. “We’ve been planning this for a long time.”

According to that plan, mission controllers would turn off Odyssey’s science instruments and verify its orbit. Finally, they would tell Odyssey to dump its fuel, and sign off. Listless and silent, Odyssey would drift around Mars, its orbit decaying over the decades, until it eventually crashes down on the same martian surface that it so meticulously mapped.

The budget circle of life

Odyssey’s budgetary shakedown is part of a broader realignment of NASA’s Mars exploration strategy that focuses on bringing back samples from Mars — something for which scientists have been advocating for decades.

Returning samples from Mars “is going to change the way we think about Mars again,” Glaze says. “We are far, far closer than we’ve ever been to making this a reality.” But, although that could very well happen, it might force us to give up on a working mission. And, according to Hynek, “You’re going to lose a lot by shutting [Odyssey] off.”

Christensen and others are still considering unique ways to save Odyssey, including potentially converting it into a spacecraft for use by students and enthusiasts. There is precedent: In 2010, a class of seventh graders in California taking part in Arizona State University’s educational program discovered a martian lava tube with a skylight. After closely studying more than 200 THEMIS images of Mars, the students were then eligible to request Odyssey take a targeted image of their site. “If Odyssey just became a student camera, I think it would be worth the money to keep it,” Christensen says. “I’m a long way from giving up on this mission.”

“We’re going to do everything we can to try to keep it going,” Glaze adds. “We’re putting forth every effort to make sure we have the capability to use the spacecraft as long as we can.”