In May, SpaceX’s Crew Dragon capsule ferried astronauts to the International Space Station from U.S. soil, the first such trip in nearly a decade. Two months later, three new missions launched for Mars to usher in a new era of robotic exploration.

The global pandemic that defined much of the year changed how scientists worked and shuttered telescopes for months. But despite these challenges, our top 10 space stories show how we pressed on with new, innovative ways to explore our universe.

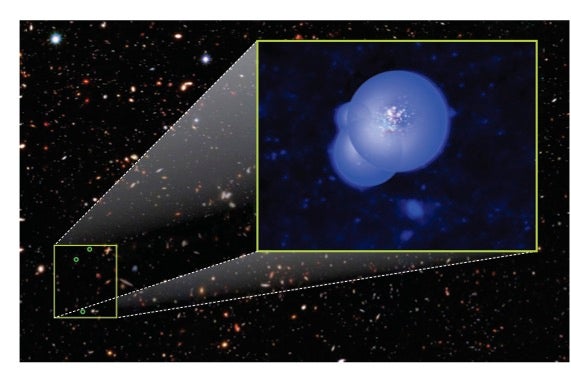

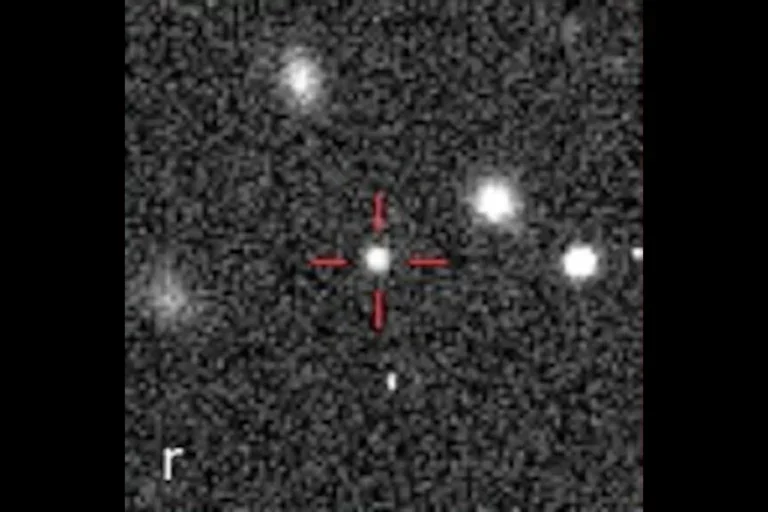

10. Earliest galaxy group found

The cosmic dark ages began 380,000 years after the Big Bang. At first, no stars or galaxies existed to emit light. But even after these objects began forming, their light remained shrouded because the universe was filled with a “fog” of neutral hydrogen atoms that absorb and scatter ultraviolet light.

Over time, energetic ultraviolet light from early objects ionized these hydrogen atoms, knocking away their electrons. This era of reionization ended 1 billion years after the Big Bang, leaving the universe transparent to light.

But astronomers aren’t sure exactly what types of objects — galaxies, black holes, or stars — were responsible for clearing the fog during reionization, says Vithal Tilvi of Arizona State University, who is part of the Cosmic Deep And Wide Narrowband (Cosmic DAWN) survey seeking to understand this era. Astronomers also aren’t sure how fast the transition from an opaque to a transparent universe occurred.

Then the survey found EGS77: three galaxies shining 680 million years after the Big Bang, when the universe was just 5 percent its current age. “[It’s] the most distant group of galaxies — and therefore the earliest group of galaxies in the universe — we have ever seen,” says Tilvi, whose team published their find February 27 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Each galaxy is generating a bubble of ionized hydrogen about 2 million to 3 million light-years across. These bubbles overlap, creating a larger, single region of space that’s free of cosmic fog, allowing light to travel freely. “So far we had [seen] individual galaxies spread across the survey areas. This is the first time we have found a group of galaxies” making the universe transparent, says Tilvi. By virtue of being in a group, EGS77’s combined bubbles allowed the team to spot fainter galaxies than could be seen if they were alone.

In the future, Tilvi says, using the same technique will allow researchers to discover more faint galaxies. That will ensure astronomers don’t underestimate the number of dim galaxies — which we know outnumber bright ones — responsible for bringing about cosmic dawn.

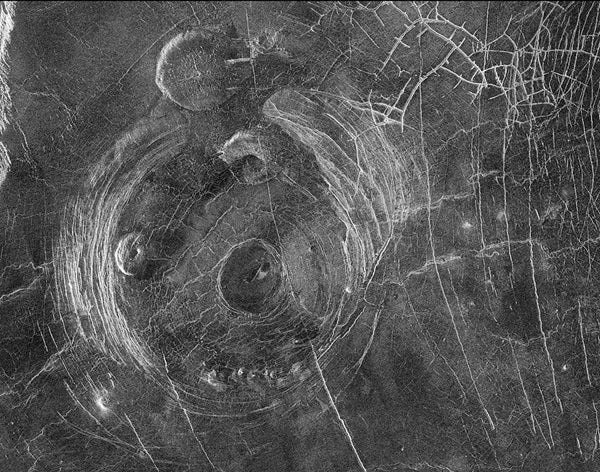

9. Mars and Venus are geologically active

On February 24, 2020, researchers released the initial results of NASA’s InSight lander on Mars. Covering the first 10 months of the mission, the findings included the conclusion that the Red Planet is seismically active.

Of 174 marsquakes recorded from February to September 2019, scientists traced two of the strongest to Cerberus Fossae. This young region has undergone volcanism and other geologic changes in the last 20 million to 2.5 million years, says Suzanne Smrekar, deputy principal investigator for InSight. “Mars’ surface is on average several billion years old, so anything in the million-year range is super intriguing,” she adds. “Where’s the energy [for the activity] coming from? Why there and not elsewhere on Mars?”

By late September 2020, InSight had recorded about 500 quakes, roughly 50 of which give clues about the planet’s deep interior, Smrekar says. By studying how seismic waves travel through the lower crust, scientists have learned Mars’ crust is likely intact — “more like Earth’s than the Moon’s, where the crust has been pummeled and fragmented by impacts,” she says. “Overall, we are seeing a level of seismicity within the predicted range,” Smrekar concludes — except when it comes to bigger quakes, which are rarer than expected. “It may be that we just need to be patient, or maybe Mars is behaving in a way that we didn’t anticipate.”

Smrekar — who is also principal investigator of the Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography & Spectroscopy (VERITAS) mission currently under consideration for NASA funding, and who worked on the Magellan spacecraft that orbited Venus in the early 1990s — isn’t surprised. Despite the fact that the idea of Venus as a geologically dead planet has persisted, she says, “There [have been] a bunch of recent studies that point to current, geologically recent activity on Venus.”

And research into Venus is gaining even more momentum, as evidenced by No. 2 on this list. “I’m positive this will lead to great new science,” Smrekar says.

8. Betelgeuse blows its nose in our direction

In late 2019, Orion the Hunter began having shoulder problems: Betelgeuse, the red giant star that marks the figure’s right shoulder, started dimming dramatically. While astronomers know the star varies regularly over time, this episode was both unexpected and unusually extreme, noticeable even to naked-eye observers. By mid-February 2020, the star was just one-third its normal brightness and the astronomical community was abuzz — could this signal an impending supernova explosion?

But, spoiler alert, Betelgeuse remains a fixture in our night sky. It’s also back to normal brightness. So, what happened? An August 13, 2020, paper in The Astrophysical Journal provides the explanation. Based on Hubble Space Telescope observations leading up to the so-called “Great Dimming Event,” the authors concluded the star “sneezed” out a cloud of hot gas from its photosphere in fall 2019. By the time it reached millions of miles from the star, the cloud had cooled and condensed into dust grains that temporarily obscured the star’s southern hemisphere and made Betelgeuse appear dimmer.

According to study leader Andrea Dupree of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, events like this can show astronomers how stars like Betelgeuse lose mass — a process that is poorly understood.

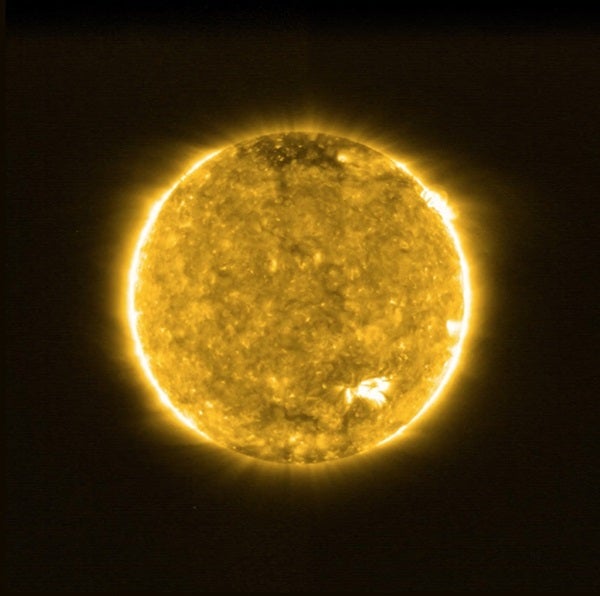

7. Solar science enters a golden age

Although the closest star to Earth has been widely studied, the Sun still maintains some secrets. But perhaps not for long, as a veritable armada of solar science missions may soon unlock the last mysteries.

“In my opinion, the most interesting and significant solar discoveries have been coming from the Parker Solar Probe,” says Russell Howard, head of the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory’s Solar and Heliospheric Physics branch in Washington, D.C., and principal investigator for Parker’s Wide-field Imager for Solar PRobe (WISPR). Parker, which launched in 2018, “has been making both in situ and remote sensing observations from … much closer to the Sun than ever before.” Recently, the probe revealed that the Sun’s magnetic field is surprisingly complex far from the star. The simple dipole (like a bar magnet) structure researchers expected is there, Howard says, but overlaid with other structures as well, which scientists are now modeling to better understand.

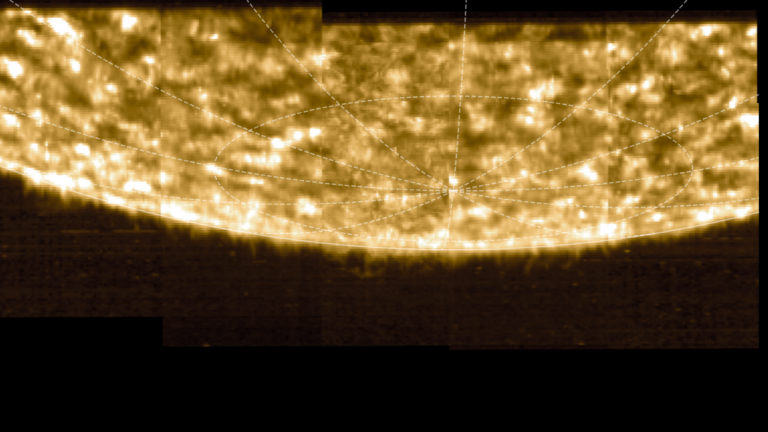

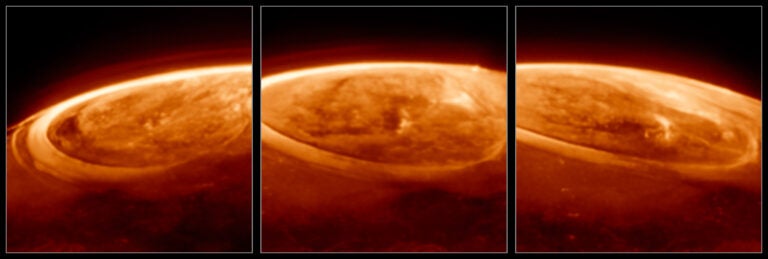

Soon to observe in tandem with Parker is the European Space Agency/NASA Solar Orbiter spacecraft. After launching February 9, 2020, the probe made its first close pass of the Sun in mid-June. Its 10 instruments are working as expected — or better, says Howard, who is also principal investigator of the Solar Orbiter Heliospheric Imager (SoloHI).

SoloHI appears less affected by stray light than estimated and the magnetometer observed the signs of a coronal mass ejection event. Ultraviolet images show never-before-seen bright spots on the Sun. Small and ubiquitous, each is about a millionth to a billionth the size of a traditional solar flare. Researchers have christened them “campfires,” and suspect they are either miniature solar flares or perhaps related to nanoflares, which are thought to heat the Sun’s outer atmosphere, the corona.

The more sensors in the solar wind, the better, Howard says, because that gives scientists a more comprehensive view. Parker and Solar Orbiter are also joined by the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, the two Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory probes, the BepiColombo mission, and the ground-based Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope. “I am extremely excited about this ‘golden age’ of solar observations from five different space probes and the ground-based observations,” Howard says.

6. Crew Dragon ferries astronauts, a first

Since the retiremenT of the Space Shuttle Program in 2011, NASA astronauts have depended on Russia for rides to the International Space Station (ISS). But that’s not the case anymore. In a historic first, the private spaceflight company SpaceX launched two American astronauts into orbit May 30 as part of the Crew Dragon Demo-2 mission.

The launch, which was streamed online and aired by all major TV news networks, was viewed live by some 10 million people. The following day, the spacecraft docked with the ISS and its passengers, astronauts Doug Hurley and Robert Behnken, migrated to the orbiting research lab, where they spent the next two months testing Crew Dragon and carrying out science experiments.

Once their stint on the ISS concluded, the pair hopped back into Crew Dragon and set course for home. Shortly after 1:48 P.M. CDT on August 2, Hurley and Behnken splashed down in the Gulf of Mexico. The capsule was plucked from the water by the recovery ship Go Navigator shortly thereafter. Out of an abundance of caution, the astronauts’ departure from Crew Dragon was delayed due to the detection of low levels of a potentially toxic propellant called nitrogen tetroxide. After it was purged from the spacecraft, the astronauts safely exited the sealed crew cabin, proving the privately built capsule’s worth.

On November 15, the first official Crew Dragon mission, dubbed Crew-1, blasted off for the ISS. After docking with the space station the next day, NASA astronauts Michael Hopkins, Victor Glover, and Shannon Walker, as well as JAXA astronaut Soichi Noguchi, boarded the ISS, where, as of the time of this writing, they continue to work.

Now that two Crew Dragon spacecraft have successfully delivered astronauts to the ISS, the future once again looks bright for American crewed spaceflight.

5. A triple comet surprise

When it was Discovered August 30, 2019, the second-known interstellar visitor to our solar system, Comet 2I/Borisov, hadn’t yet made its closest pass to the Sun (called perihelion). Unlike 1I/2017 U1 ‘Oumuamua, which was spotted only after it had already rounded our star, astronomers were able to watch Borisov before, during, and after its December 8, 2019, perihelion pass.

John Noonan of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona, Tucson, was part of a team that observed Borisov with the Hubble Space Telescope in late December and early January. They looked for carbon monoxide (CO) sublimating, or turning directly from solid ice to gas, off the surface. “[CO] sublimates at very low temperatures. So, if you see carbon monoxide, that tells you something has been cold for a very long time,” he says.

On Borisov, “there was more carbon monoxide than there was water, which is pretty much unheard of” for comets in our own solar system, Noonan says. The out-of-whack ratio means Borisov “very clearly formed in a system … very different than our own.” That place could have been around a red dwarf star — stars smaller and cooler than our Sun, and commonplace throughout the galaxy.

As Borisov faded from headlines, comet enthusiasts eagerly awaited C/2019 Y4 (ATLAS), whose mid-May glow astronomers predicted would be rivaled only by Venus. But on April 11, amateur astronomer Jose de Queiroz snapped a photo that showed the comet breaking up. Hubble images on April 20 and 23 confirmed the comet had fragmented into several pieces — an interesting turn of events for researchers, but one that quashed any chances of ATLAS achieving “great comet” status.

NEOWISE spent several weeks delighting skywatchers as the brightest Northern Hemisphere comet since C/1995 O1 (Hale-Bopp). “What a great little comet!” astrophotographer John Chumack wrote in an email on July 29 to Astronomy. By then, the comet was a 4th-magnitude target low in the northern sky. “Over the last few weeks, NEOWISE put on a nice show for us Northern Hemisphere observers. Some of my astronomy friends in the Southern Hemisphere have now got to glimpse it and they are reporting it still fading,” he said.

4. First midsized black hole detected

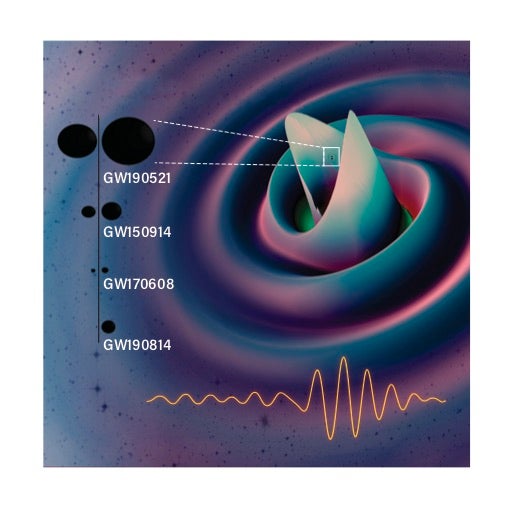

Black holes come in a variety of sizes, ranging from a few to billions of times the mass of the Sun. Although there is ample evidence for stellar-mass and supermassive black holes, there is surprisingly little proof of their middleweight brethren. But on May 21, 2019, scientists at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) and the partnering Virgo site received the first convincing sign: gravitational waves that point to the violent birth of an intermediate-mass black hole (IMBH).

After spending more than a year scrutinizing the signal (called GW190521), which lasted just a tenth of a second, on September 2, 2020, an international team of researchers released two papers detailing their results: The gravitational waves originated halfway across the universe and were produced when two hefty black holes merged to create an IMBH about 142 times the mass of the Sun. Their collision also released a stupendous amount of energy, equivalent to roughly eight solar masses, as gravitational waves.

Although this detection confirms that IMBHs exist, it also raises questions. The progenitor black holes weigh in at 66 and 85 solar masses, so the larger one firmly falls in the “pair-instability mass gap.” When most massive stars die, they leave behind a black hole. But when a star weighs 130 to 200 solar masses, photons in its core become so energetic they morph into electron-antielectron pairs, which can’t fully combat gravity. The star becomes extremely unstable and, after going supernova, leaves nothing behind.

“This event opens more questions than it provides answers,” LIGO member Alan Weinstein, professor of physics at Caltech, said in a press release. “From the perspective of discovery and physics, it’s a very exciting thing.”

3. The Milky Way does the wave

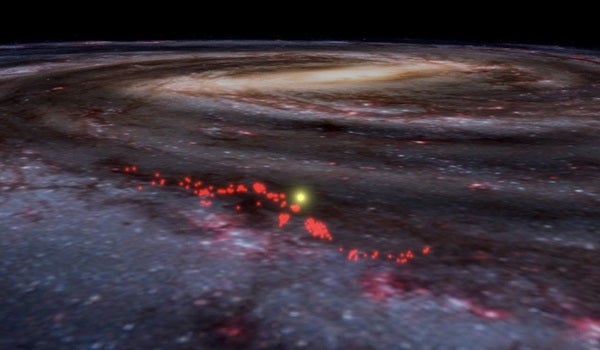

Because we are embedded within the Milky Way Galaxy, mapping its large-scale structure is challenging. That is especially the case for galactic star-forming regions, huge clouds of gas and dust whose distance is difficult to measure because they aren’t points like single stars. But new work by Harvard University astronomers published January 7, 2020, in Nature dramatically increased the accuracy of distance measurements to nearby star-forming regions. It also uncovered something unexpected: the Radcliffe Wave.

Nearly 9,000 light-years long and 400 light-years wide, this snaking line of interconnected star-forming regions rises above and dips below the plane of our galaxy. It lies less than 500 light-years from Earth at its nearest point and connects molecular clouds in Orion, Taurus, Perseus, Cepheus, and Cygnus.

“Prior to the discovery of the Radcliffe Wave, star-forming regions were studied in relative isolation. The Radcliffe Wave showed that all these regions are connected on the grandest of scales, via tendrils of filamentary gas, which is something we never knew before,” says Catherine Zucker, whose Ph.D. work at Harvard led the effort to pin down distances to the star-forming regions that make up the Wave. That work involved combining observations of the way intervening dust and gas makes starlight appear redder with accurate distance measurements to those stars from ESA’s Gaia spacecraft.

“Since this effect [reddening] is observable throughout our solar neighborhood, it allowed us to determine the distances to a huge sample of star-forming regions, using the same technique, for the first time,” Zucker says. “Previous distance techniques were piecemeal, obtained inhomogeneously on a cloud-by-cloud basis.”

Her technique revealed, to a factor of five times better than previous measurements, the distances to nearby star-forming regions — and the Radcliffe Wave. “In the future, this will force us to reframe our understanding of star formation on small scales (i.e., within individual molecular clouds) in a larger galactic context,” she says.

2. Astronomers spy phosphine on Venus

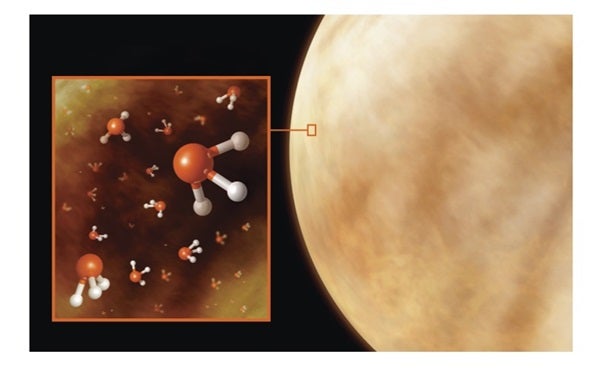

Venus is a sizzling world thought by many to be inhospitable to life. Surface temperatures are hot enough to melt lead — almost 900 degrees Fahrenheit (480 degrees Celsius) — while the pressure at ground level is more than 90 times that of Earth at sea level. But that hasn’t stopped some, including Carl Sagan, from proposing that life could exist in the more temperate clouds of our sister planet. And now, there could be evidence to support that hypothesis — albeit controversial evidence.

In a paper published September 14 in Nature Astronomy, researchers presented observations of an inexplicable surplus of the rancid gas phosphine in the clouds of Venus. On Earth, microbes produce most phosphine, though it can also be created abiotically under great temperatures and pressures. Measured at a level of some 20 parts per billion, the researchers behind the new paper say no known geological activity or exotic catalysts — such as lightning or meteorites — can explain the strength of their observed signal.

“We are not claiming we have found life on Venus,” said co-author Sara Seager, an MIT planetary scientist, in a press conference. However, she added, they can’t explain the phosphine’s origin.

Many find the unexplained biosignature, or potential evidence for past or present life, tantalizing. However, others remain skeptical. Chemical compounds each have a unique spectrum, or fingerprint, that depends on the wavelengths of light they absorb. Although the researchers detected this fingerprint of phosphine with two independent telescopes at different times, they only saw it at a single wavelength — one that sulfur dioxide happens to absorb as well.

“As a geochemist, I always worry about detection from one peak,” says Justin Filiberto of the Lunar and Planetary Institute. “A single line is a coincidence, not a detection,” adds astrobiologist Kevin Zahnle of NASA Ames Research Center in California. Still others are concerned about the quality of the noisy data itself, which means many groups are already reanalyzing it.

But if the detection holds up, “it demands follow-up,” says Bethany Ehlmann, a planetary scientist at Caltech who was not part of the discovery team. “The top three destinations to look for life in the solar system are Mars, Enceladus, and Europa — and now we should perhaps add Venus to the list.”

Editor’s note: Since the publication of this story, new research has come out that suggests the detected signal may have been from sulfur dioxide instead of phosphine.

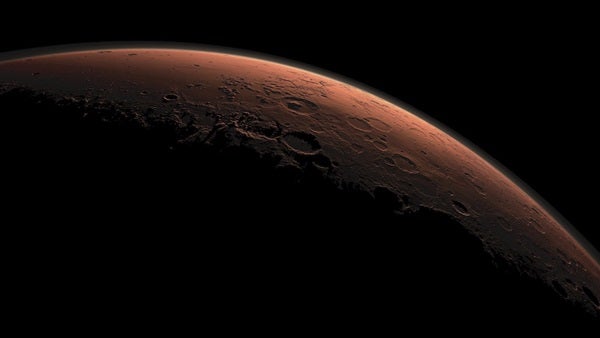

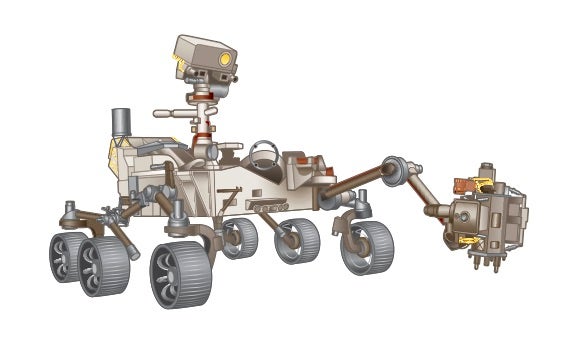

1. Misson to Mars

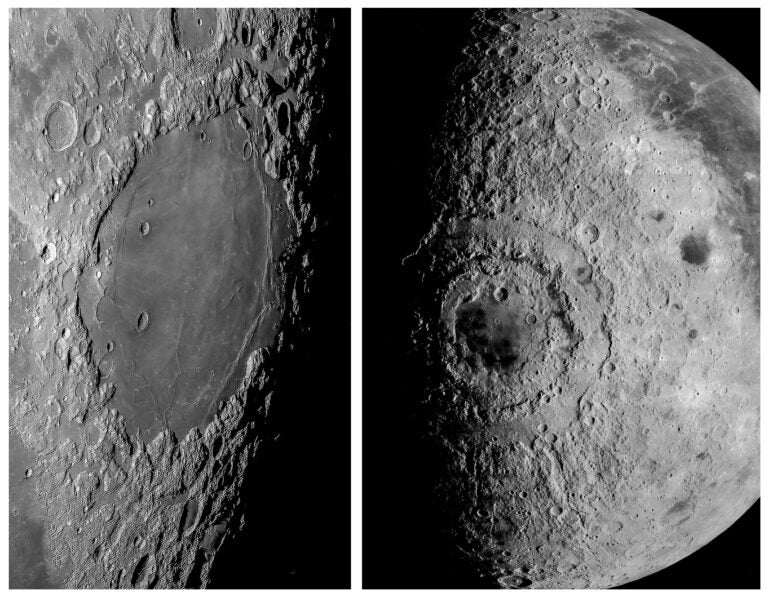

As usual, the Red PlaneT has had quite a year. Not only did NASA’s InSight lander detect hundreds of marsquakes shaking the planet, but ESA’s Mars Express orbiter found more signs that the world has several underground saltwater lakes buried beneath its south pole. Perhaps most importantly, however, 2020 saw three new spacecraft set forth for the Red Planet, taking advantage of a once-every-26-months alignment that shortens the time and distance required to get from Earth to Mars.

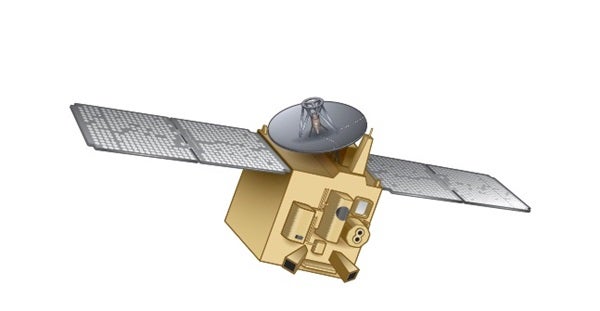

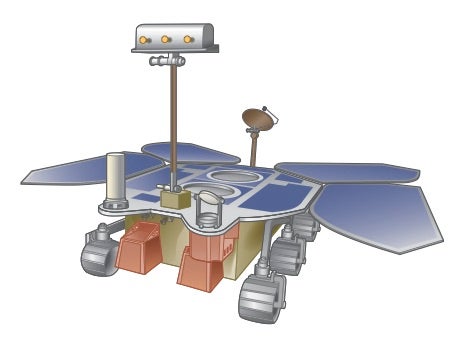

As its first interplanetary mission, the United Arab Emirates launched an orbiter named al-Amal (meaning “Hope”) July 19. The craft is equipped with both an infrared and ultraviolet spectrometer — the former meant to investigate dust, water, and ice in Mars’ lower atmosphere and the latter meant to study oxygen and carbon monoxide in the upper atmosphere. Additionally, the craft carries a multiband camera that can achieve resolutions better than 5 miles (8 kilometers) per pixel. Altogether, Hope aims to paint a more comprehensive picture of the Red Planet’s atmosphere.

With all these missions expected to reach the Red Planet in February, 2021 is bound to be a big year for Mars.

Stories to watch for in 2021

- The missions that left Earth for Mars in 2020 — the UAE’s Hope, China’s Tianwen-1, and NASA’s Perseverance — will all reach the Red Planet in February 2021.

- NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test, or DART mission, will launch July 22, 2021, to binary asteroids Didymos and Dimorphos. The agency’s Lucy spacecraft is scheduled to launch October 16, 2021 — the first mission to Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids.

- Because of technical difficulties and the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, NASA has updated its target launch date for the James Webb Space Telescope to October 31, 2021.

- Also delayed due to coronavirus, the Indian Space Research Organisation’s Chandrayaan-3 mission, which comprises a lander and rover, is now scheduled to launch for the Moon in late 2021.

- The ESA and Roscosmos’ robotic Luna-25 lander aims to put Russia back on the Moon with an anticipated launch date in October 2021.

- First light for the 8.4-meter Simonyi Survey Telescope at the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile is expected in October 2021.

- Both the Parker Solar Probe and Solar Orbiter will make flybys of Venus in 2021: Parker will make two, Solar Orbiter will make one.

- The uncrewed Artemis I mission, the first in NASA’s plan to return humans to the Moon, is scheduled to launch in 2021. This first mission will combine the new Space Launch System rocket and Orion crew capsule.