With the success of Apollo 14 behind them and the near tragedy of Apollo 13 firmly in the past, Apollo’s mission planners hiked the length and sophistication of the following mission. Apollo 15 was designed to be the first of the so-called J Missions, a designation in NASA’s playbook that constituted longer stays on the lunar surface with an expanded set of scientific goals.

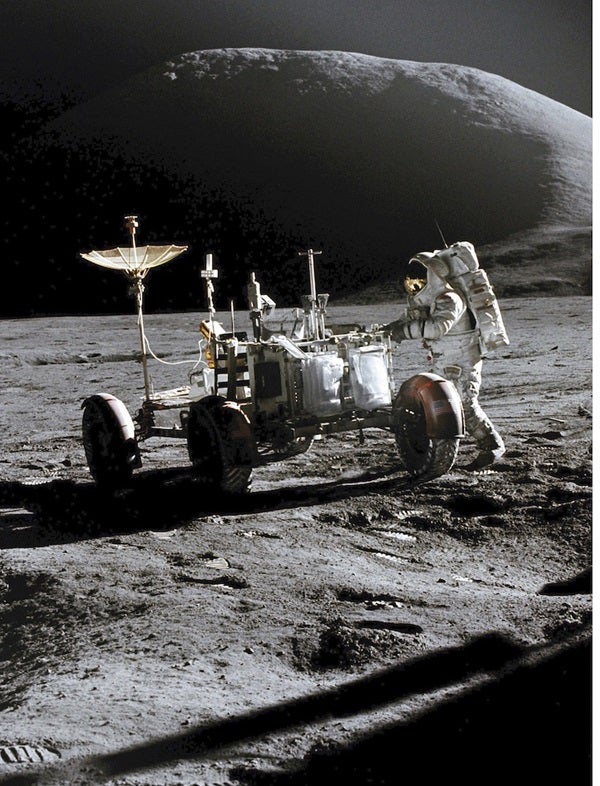

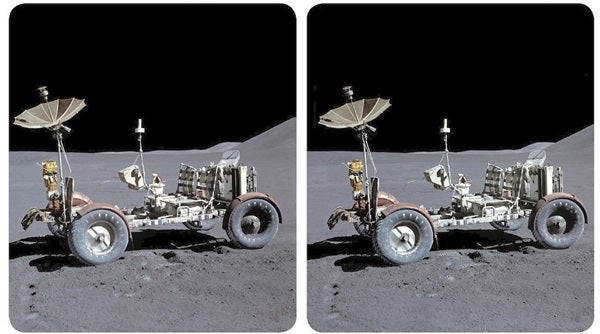

To everyone’s excitement, the mission would also be the first to carry along a Lunar Roving Vehicle, the world’s most expensive car. Now the amount of lunar territory that could be explored would also expand, as astronauts would not be limited to simply walking in the bulky spacesuits to various destinations. The lunar rover would make driving to areas on the Moon classy and comfortable, and would enable the expansion of scientific studies and also of collecting Moon rock samples from a larger area than was previously possible.

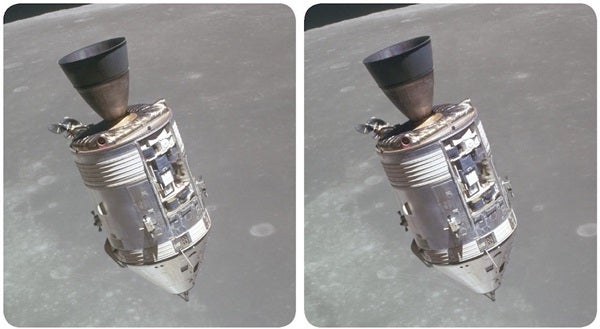

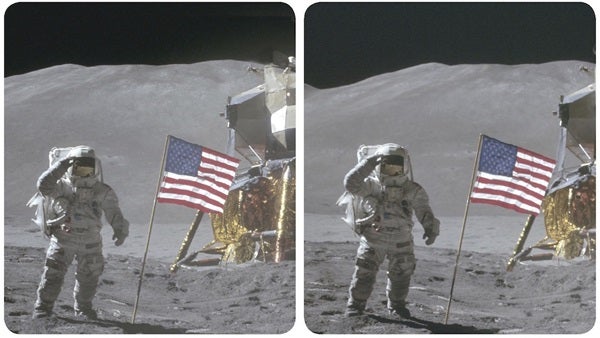

Viewing 3D images

There are two ways to view the images printed in 3D. To free view the images with no mechanical assistance, let your eyes relax as you view the photos as though focusing on a point behind them. At first you will see the two images split into four; as your eyes focus at the correct distance, the middle two images will combine to create a single, crisp 3D image. The outer two images will remain on either side of the 3D image and become blurry.

Alternatively, you can use a 3D viewer, such as the Lite OWL viewer designed by Brian May and included with the Mission Moon 3-D book, to view images in 3D. Only 5 by 2.5 inches (134 by 64 millimeters) and 0.1 inch (3 mm) thick, the Lite OWL viewer is designed for easily viewing 3D images in books, magazines, modern and vintage stereocards, and even video or other VR content on your smartphone. You can purchase individual Lite OWL viewers separately at www.MyScienceShop.com.

A cultural snapshot

After a six-month period of preparation following Apollo 14, Apollo 15 was scheduled for launch on July 26, 1971. The sweeping social and psychological change that had marked the end of the ’60s continued apace. That year in Los Angeles, Charles Manson and his followers were found guilty of the Tate-LaBianca murders and, just a few days later, a major earthquake rocked the area. In the spring, half a million people marched in Washington to protest the Vietnam War, and The New York Times began to publish the Pentagon Papers, a classified study of the situation in Vietnam. In New York, workers completed the top floor of the South Tower of the World Trade Center, making it the tallest building in the world.

The world of music and pop culture also raced forward with rapid-fire change. Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin were gone, victims of excess; Jim Morrison of The Doors would follow shortly in the summer of 1971. Members of the Beatles experimented with solo careers. In London, a new band formed in 1970 began to rehearse for their first album. It was called Queen, and consisted of Freddie Mercury, Brian May, John Deacon, and Roger Taylor. With that lineup, the band played its first show outside London less than a month before the launch of Apollo 15.

The intrepid crew

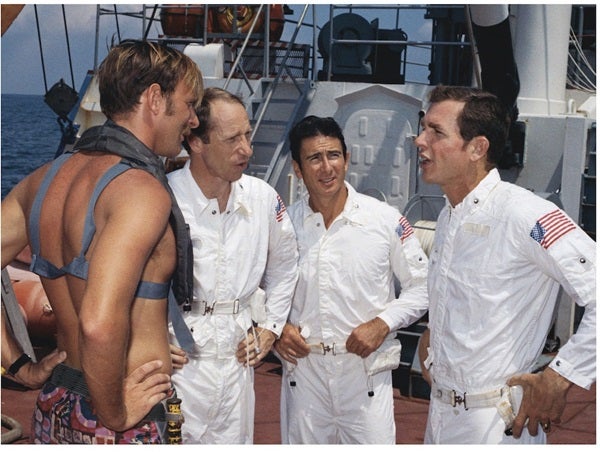

The Apollo 15 crew consisted of one experienced spaceflight veteran and two rookies. David Scott, the commander, was a 39-year-old Air Force officer and test pilot. Texas-born Scott had been chosen as one of NASA’s third astronaut group and subsequently teamed with Neil Armstrong as part of the Gemini VIII mission. He then served as Command Module pilot on Apollo 9 alongside James McDivitt and Rusty Schweickart. Scott’s experience would be key for the ambitious narrative expected to come out of Apollo 15. He would be joined by Command Module Pilot Alfred Worden, a 39-year-old Michigan-born man who had been an Air Force pilot and was selected as an astronaut candidate in 1966. The mission’s Lunar Module pilot was James Irwin, age 41, who had a background as an aeronautical engineer and Air Force test pilot. Irwin was Pittsburgh-born and was selected in the 1966 group of astronauts along with Worden. The crew’s backups consisted of Commander Dick Gordon, Command Module Pilot Vance Brand, and Lunar Module Pilot Jack Schmitt.

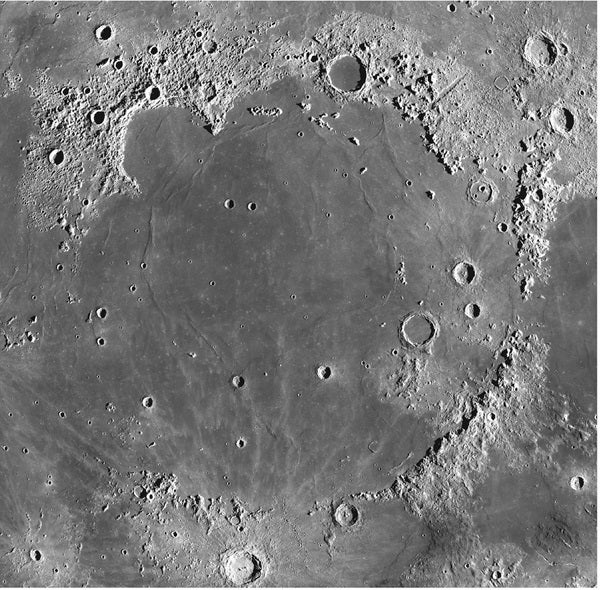

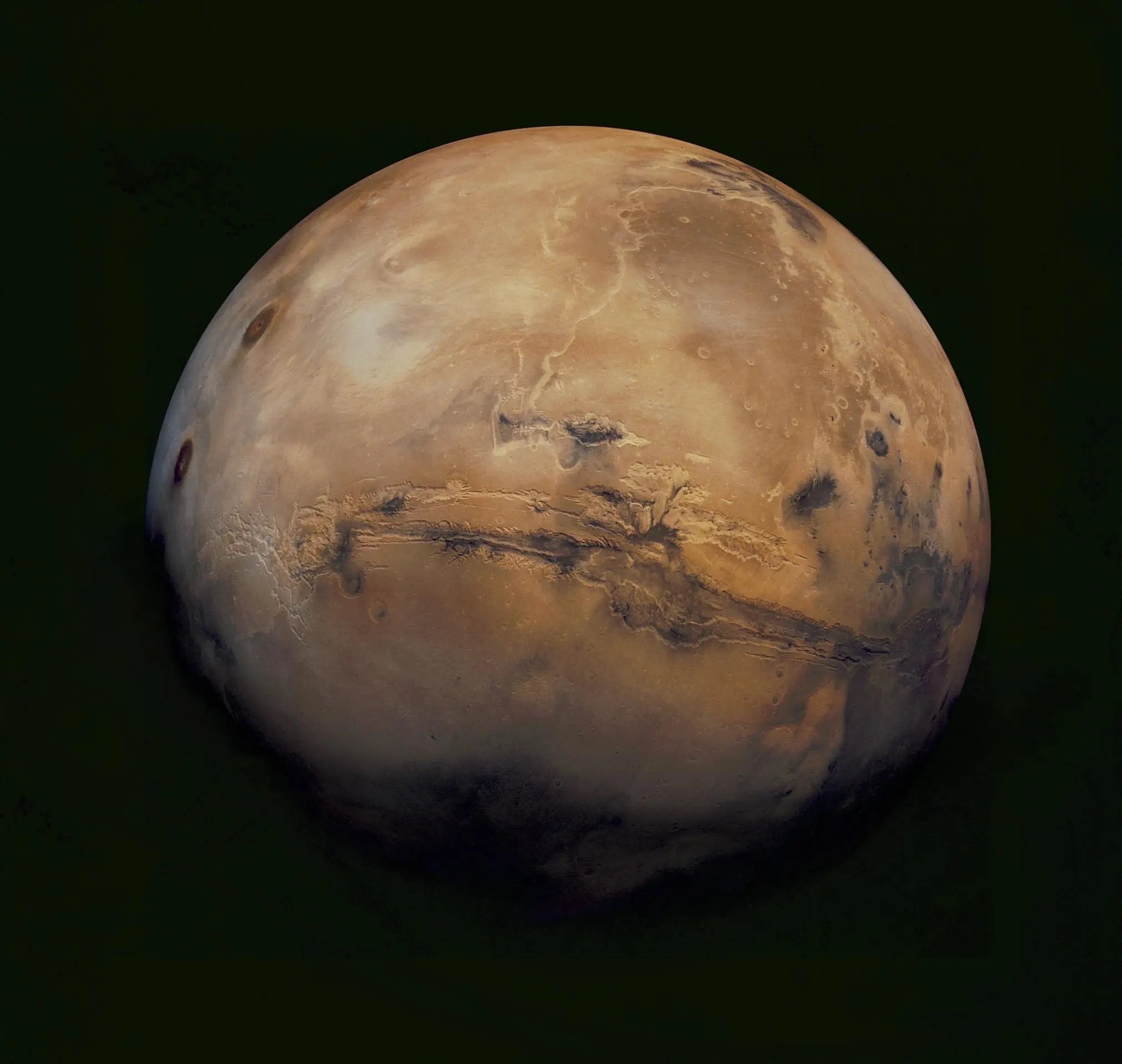

The design for Apollo 15 was ambitious and exciting. The target area was near Hadley Rille, a section of the lunar surface marked by flexure, appearing as a groove cut into the lunar floor. Nearby stands Mons Hadley, a mountainous rise that stretches roughly 13,000 feet (4,000 meters) above the floor below and has a diameter of about 15 miles (25 kilometers). Hadley Rille lies within an area of the Moon known as Mare Imbrium, the Sea of Rains. On the other side of the landing site from Hadley Rille are the lunar Apennine Mountains, a rugged range forming the southeastern rim of Mare Imbrium. The specific area where the spacecraft would land was dubbed Palus Putredinis, the Marsh of Decay.

The Lunar Roving Vehicle

Rather than spending about a day on the lunar surface, as had Apollo 11, 12, and 14, this fourth mission to explore the Moon with humans would allow three days of investigation. Worden would stay within the Command Module, nicknamed Endeavour, in lunar orbit. Scott and Irwin would descend to the surface in the Lunar Module (LM), callsign Falcon, to explore the Moon, conduct scientific experiments, and collect Moon rocks, all while they drove around.

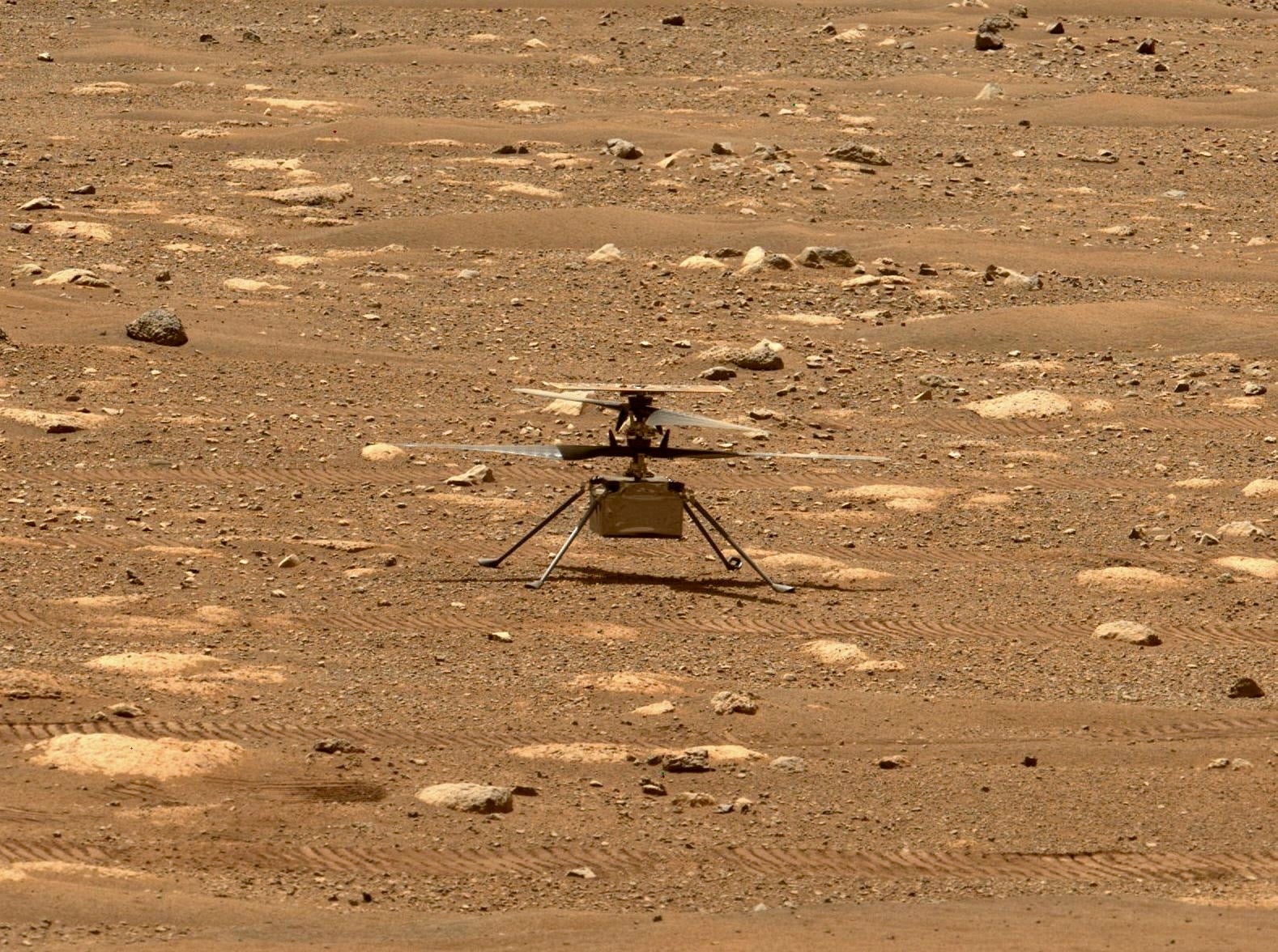

The lunar rover was the result of a complex engineering project that had been developed for years. Manufactured by Boeing and General Motors, the lunar rover immediately acquired the name “Moon buggy,” in a play on “dune buggy.” It was a battery-powered four-wheeled cart that would transport not only the astronauts but also ample rock samples and lots of scientific equipment. The concept of a lunar rover originated with Wernher von Braun in the early 1950s. About a decade later, von Braun, now developing NASA’s heavy lift rockets with his team at Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, again wrote extensively about the need for a lunar roving vehicle.

NASA commenced studies of various roving vehicle concepts at Marshall and some alternatives were far more complex than the final result. Some designs incorporated mobile laboratories, while many designs had sheltered canopies for the astronauts. The original idea was that a second rocket launch could blast a complex, large rover to the Moon. But then the U.S. Congress became concerned with the Apollo budgets, necessitating a single launch for each Apollo mission. This meant that the vehicle had to fold up and be carried along with the LM, to be unpacked and set up on the Moon’s surface.

Between 1965 and 1967, NASA engineers concluded that a vehicle of some type was critical to make the most of lunar studies from the Apollo program. By 1969, they chose the Lunar Roving Vehicle as the winning concept and sanctioned its creation at Marshall, under von Braun’s watchful eye. The final development and construction of the lunar rovers took place just before the Apollo 11 landing. Boeing oversaw the project and General Motors, as a subcontractor, provided the wheels, electric motors, and suspension. The final cost of the lunar rover program was $38 million; it provided four cars. Many have since said, with a twinkle in their eye, that the lunar rovers, at $9.5 million each, are the world’s most expensive cars — leaving Ferraris and Lamborghinis in the dust!

The lunar rovers really turned out to be a phenomenon that changed the functionality of the Apollo missions. They expanded the range of the lunar explorers, although that range was functionally limited to remain in long-range walking distance of the LM, should a malfunction with the rover occur. These cars had a designed top speed of 8 mph (13 km/h), although during Apollo 17, Gene Cernan reached a velocity of 11.2 mph (18 km/h), making his drive the fastest on the surface of the Moon.

These lunar vehicles weighed some 460 pounds (210 kilograms) and stretched 10 feet (3 m) from front to back. The frame was constructed from aluminum alloy tubing and the three-part chassis was hinged so it could be folded inside the LM and unpacked and set up on the Moon’s surface. The two side-by-side seats were made of aluminum tubing and had nylon webbing. An armrest separated the seats and each had footrests. The wheels consisted of a spun aluminum hub with tires made of steel strands woven together and coated by zinc, then covered with titanium chevrons to help achieve maximum traction on the powdery lunar surface.

Each wheel on the vehicle had its own electric drive, and the vehicle could be maneuvered by front and rear steering motors. Front and rear wheels could turn in opposite directions for maximum maneuverability, or they could be decoupled to provide specific aid in steering and traction. The energy to make this package move came from two silver-zinc potassium hydroxide batteries, each with 36 volts, that powered the drive and steering motors, and a utility outlet powered the communications equipment and a color TV camera mounted on the rover’s front. The whole thing could be controlled with a T-shaped handle by the astronaut driver.

To deploy the rover, the astronauts had to use ropes and cloth tapes to operate pulleys and braked reels. Stored in a bay inside the LM, the rover had to be released by an astronaut who climbed the LM’s ladder; his companion could slowly unfold the chassis of the rover using reels and tapes. Next, the rover was moved down from the bay and could be set up on the ground, its rear wheels locking into place. The entire frame could then be brought down and final assembly achieved: The astronauts assembled the final aspects of the seats and footrests, switched on the vehicle’s electronics, and the car was ready for a lunar test drive.

Getting underway

With the rover packed along with everything else in the mighty Saturn V rocket, the crew of Apollo 15 prepared for launch on July 26. In midmorning, the rocket shot skyward and the mission was underway. The launch did not go flawlessly, however. The first stage did not completely shut off on time, briefly raising the possibility of the first stage engines colliding into the second stage boosters, which would have aborted the mission. Exhaust from the second stage engines also damaged the onboard telemetry package. Despite these initial concerns, the rocket performed adequately and lifted the spacecraft into an Earth parking orbit. After some two hours, the third stage ignited and sent the spacecraft shooting toward the Moon.

Following the three-day cruise to the Moon, the spacecraft passed behind the lunar farside and the engine on the Command/Service Module burned for six minutes, placing the spacecraft into the right configuration for a LM landing at Hadley Rille. As they orbited the Moon, gazing down at its gray surface, the astronauts prepared for the undocking of the LM and its descent. On the first attempt to undock the Command/Service Module from the LM, however, the astronauts encountered a glitch. The Command/Service Module had a faulty hatch, it turned out. It was resealed by Worden. The separation then occurred, with Scott and Irwin in the LM and Worden remaining in the Command/Service Module.

The two descending astronauts stood in the tightly packed LM, as had their predecessors, for the slow downward movement. As they fell gradually toward Hadley Rille, the astronauts discovered they were some 3.7 miles (6 km) east of the target landing spot. Scott then took control of the descent and maneuvered Falcon further toward the target. The craft gently fell and touched down just a few hundred yards from the intended site. Irwin announced that a landing probe on one of the legs touched down, establishing contact, and Scott cut the engine. Despite its gentle nature, this descent was faster than previous Apollo missions — faster than a hotel elevator — at some 7 feet (2 m) per second.

“Okay, Houston. The Falcon is on the Plain at Hadley,” blurted Scott. In a lunar landing first, one of the LM’s legs had landed in a small crater, tilting the craft by about 10° from level so the LM appeared skewed in images, but this didn’t create a functional problem. Missing the landing spot by a few hundred yards was also not alarming, as the rover would make travel easier.

Rather than exiting the LM quickly, as previous missions had, Scott and Irwin stayed within Falcon for the rest of their day to stay on a normal sleep schedule. Before falling asleep, however, Scott photographed the lunar scene from the LM’s top docking hatch, standing up and poking his head outside the LM, shooting the surroundings with a 500mm lens. He recognized features the astronauts had studied on maps: the Mons Hadley massif, Mons Hadley Delta (another massif), the Swan Range, the Silver Spur (a rock formation), Bennett Hill, Hill 305, and the North Complex (a group of hills). Scott returned through the hatch and repressurized the LM. Then Scott and Irwin went to sleep.

The first excursion

As the astronauts slept, Houston controllers became concerned with falling pressure readings from the descent stage oxygen tanks in the LM. They let Scott and Irwin sleep, however, and in the end woke them an hour early to switch into a high-telemetry-rate mode. This allowed the controllers to see that a valve was open and the astronauts had lost a little less than 10 percent of their oxygen. But the supply was still more than ample.

With the astronauts awake, they prepared for the first of three long moonwalks. Scott became the seventh human to climb down onto the Moon and said: “As I stand out here in the wonders of the unknown at Hadley, I sort of realize there’s a fundamental truth to our nature. Man must explore. And this is exploration at its greatest.” Some seven minutes later, Irwin joined him on the lunar surface and the astronauts unpacked equipment stowed into the LM, including the rover. They positioned the TV camera, and then Scott had the privilege of the first drive of a rover on the Moon’s surface. He found only the rear-wheel steering was working and the suits didn’t bend much when they sat down in the car, making driving a little strained. They reclined backward to ease the strain, which worked reasonably well.

Starting off at about 6 mph (9 km/h), the astronauts began a planned circuit of activities. They drove along Hadley Rille, which made finding targets relatively easy. First, they arrived at Elbow Crater, a 1,115-foot-wide (340 m) depression. The mission now focused on geological activities, collecting samples, and photography. They pressed on a distance of 1,640 feet (500 m) to St. George Crater, a 1.5-mile-wide (2.4 km) pock on the Moon. They did not see the amount of ejecta they had hoped for, which would be geologically intriguing. So instead of spending lots of time there, they moved on to a boulder they noticed in the open, near a tiny crater. Taking samples, they tried to roll the rock and ended up chipping pieces off of it. They used a rake with tines set 0.4 inch (1 centimeter) apart to collect samples of pebbles from the area. They also took core samples by driving tubes down into the powdery lunar surface.

Moving again, Scott and Irwin bypassed a planned stop at Flow Crater because of time constraints, and pressed on toward the LM. They stopped at Rhysling Crater and, on their final push back to the LM, Scott spotted a large piece of vesicular basalt that looked tempting. He stopped the rover, grabbed the rock, and carried it into the rover while Irwin distracted controllers in Houston. Because Scott stalled for time by saying his seatbelt had loosened, this rock is called the Seatbelt Basalt.

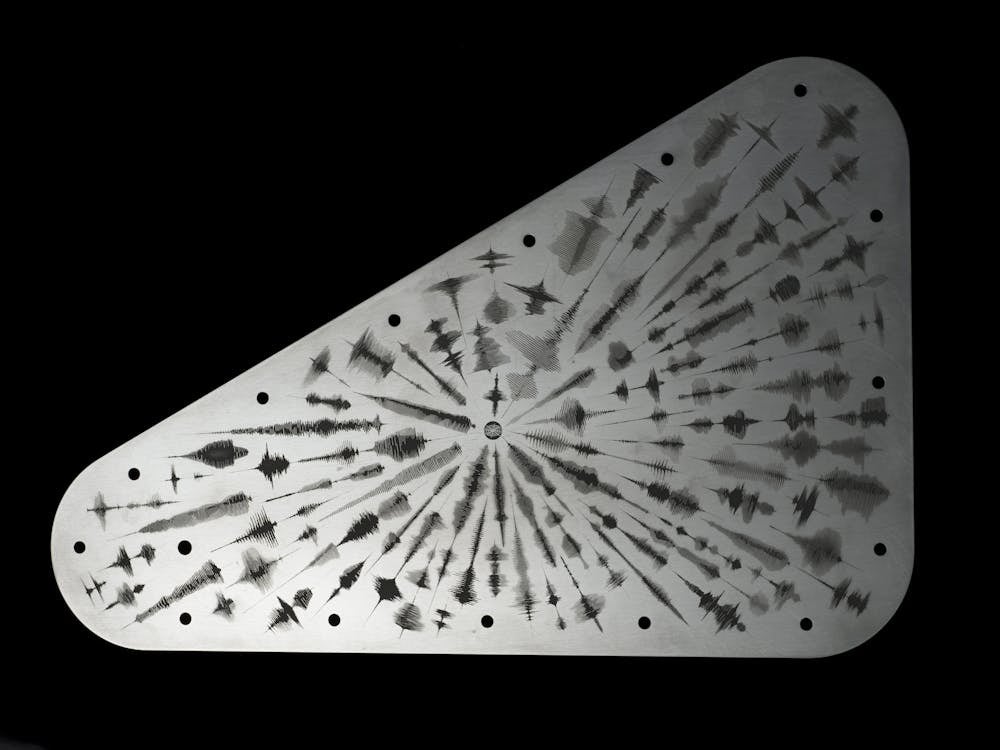

At the LM, the duo set up the normal Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package, or ALSEP, set of experiments, including a seismometer, magnetometer, solar wind spectrometer, and other instruments. After more than six and a half hours of activity, the weary pair climbed back into the LM, ready to rest after such exertion. Irwin’s water bag had not worked properly, so he had gone through the whole surface activity without fluids.

The second moonwalk

Some 16 hours later, on Aug. 1, Scott and Irwin commenced their second extravehicular activity. They would again focus on the Mount Hadley Delta complex, but this time headed directly to a site to the east of the previous day’s action. They moved along the planned route but, unexcited by some of the visuals they encountered, skipped some of the planned sites. They took samples from a 3-foot-wide (1 m) crater, finding breccias and porphyritic basalt. Scott then moved to a larger crater but found the rocks inside it too large to sample. Houston asked the pair to dig a trench to study soil characteristics, which Irwin did while Scott photographed the exercise.

They then returned to the rover and drove a long distance to find a 10-foot (3 m) boulder, noticing a greenish hue on it caused by magnesium oxide. The astronauts then traversed to Spur Crater, a 320-foot-wide (100 m) depression that sank 66 feet (20 m) into the lunar ground. They took samples and noticed white mineral veins in some of them, and a greenish hue in the soil that they determined was caused by the gold color of their visors.

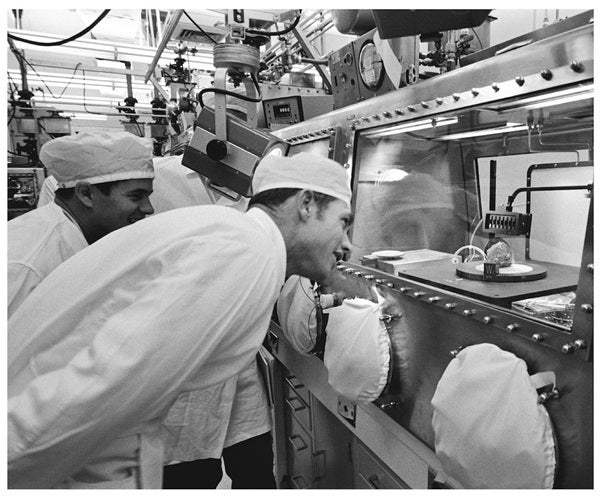

Then, in a moment of triumph, they collected what has since become the most famous lunar sample taken from the Moon during any Apollo mission. What was labeled as Lunar Sample 15415 looked initially like a partially crystalline rock, but on further examination, the astronauts saw it was nearly completely plagioclase, a tectosilicate feldspar mineral. At first, they — and scientists who studied this sample — believed the explorers had found a piece of the lunar crust. The media dubbed the sample Genesis Rock. Analysis later showed the rock to be 4.1 billion years old — some half a billion years younger than the Moon’s formation. Despite this, it remains a very ancient and captivating sample.

Houston then asked the pair to collect as many small samples as they could. They raked for small samples, collecting many, and Scott struck and fractured a rock with his rake, collecting the pieces. Before they climbed back into the LM, the two attempted to repeat a task that had failed the previous day: drilling holes nearby to facilitate a heat-flow experiment. Unfortunately, their trouble continued. They set up the U.S. flag near the LM and then returned to the interior after an excursion that lasted seven hours and 12 minutes.

The final day

A third moonwalk and drive began with trying to rectify the problems the pair had with drilling holes. They extracted some core samples but continued to be frustrated with the drilling and didn’t want to waste too much time focusing on it. They filmed the rover and then traveled to Hadley Rille, arriving at a small crater. Samples collected there were soft; this area is thought to be the youngest explored by moonwalkers. They photographed the rille and looked for exposed bedrock, hoping to find ancient material. In the wall of the rille, they hoped to see layering, indicative of lava flowing over time through Palus Putredinis. Irwin found some exposed bedrock and took samples. Scott found a coarse-grained basalt with large vugs, or cavities. He carted off a football-sized rock that came to be called Great Scott, a 21-pound (9.6 kg) sample.

Back at the LM, with time running out, Scott had one more trick up his sleeve. “Well, in my left hand, I have a feather,” he said. “In my right hand, a hammer. And I guess one of the reasons we got here today was because of a gentleman named Galileo, a long time ago, who made a rather significant discovery about falling objects in gravity fields. And we thought, where would be a better place to confirm his findings than on the Moon? And so we thought we’d try it here for you. The feather happens to be, appropriately, a falcon feather for our Falcon. And I’ll drop the two of them here and, hopefully, they’ll hit the ground at the same time.”

He dropped the two and they hit the lunar surface simultaneously: a win for Galileo once again. Before ending the walk, Scott drove the rover away a distance and planted an object on the lunar surface. It was a sculpture, made of aluminum, created by the Belgian artist Paul Van Hoeydonck. Called Fallen Astronaut, it was a small astronaut figure and was accompanied by the names of American and Soviet explorers who had died in the quest for space. The names were Theodore Freeman, Charles Bassett, Elliott See, Gus Grissom, Roger Chaffee, Ed White, Vladimir Komarov, Edward Givens, Clifton Williams, Yuri Gagarin, Pavel Belyayev, Georgiy Dobrovolsky, Viktor Patsayev, and Vladislav Volkov.

Successful return

After four hours and 50 minutes, Scott and Irwin climbed back into the LM. Two days and 18 hours after they had landed, the astronauts blasted off from the Moon’s surface, rejoined Worden, and headed back to Earth. The crew splashed down in the North Pacific on Aug. 7, with 170 pounds (77 kg) of lunar samples in tow.

Apollo 15 had been the most scientifically interesting mission yet. And with the Fallen Astronaut, the anxiety between competitors had now transformed into a bond between fellow explorers.

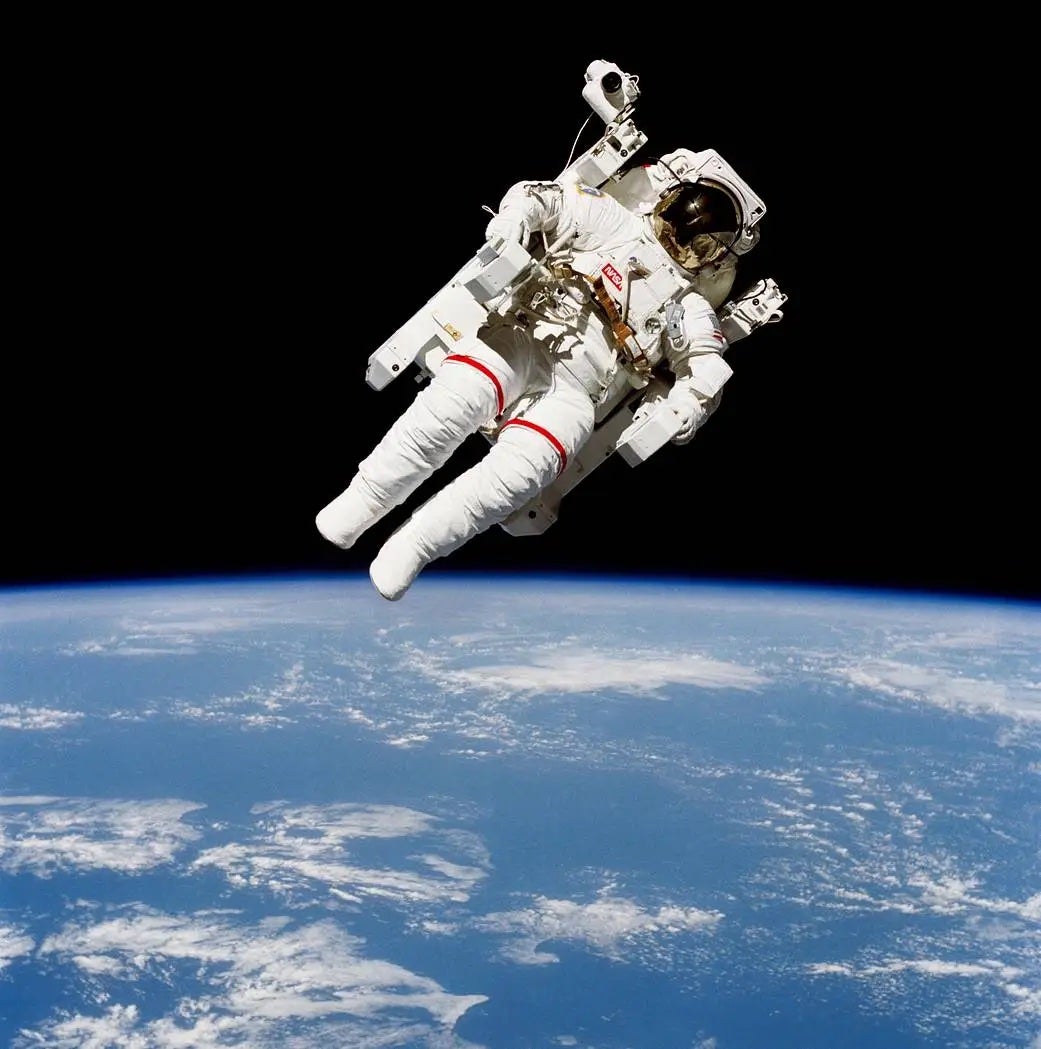

Explore from home

Mission Moon 3-D: A New Perspective on the Space Race, by David J. Eicher and Brian May (with foreword by Charlie Duke and afterword by Jim Lovell), presents the story of the historic lunar landings and the events that led up to them, told through text and three-dimensional images.

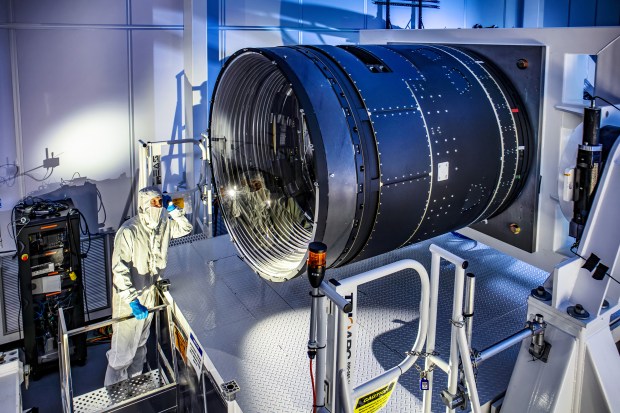

Mission Moon 3-D contains new and unique stereoscopic images of the Apollo Moon landings to show what it was like to walk on the lunar surface. The triumph of the Apollo 11 Moon landing takes center stage, with detailed stories and visually stunning images from the lunar missions that followed. The book includes 150 stereo photos of the Apollo mission and space race — the largest group ever published — and presents photos never seen before in stereo.

The book delivers a comprehensive tale of the space race. New stories appear from the astronauts, including Jim Lovell’s anecdotes about the perilous return of Apollo 13.

Mission Moon 3-D also includes a history of the music and special movements of the 1960s and beyond that transformed the world, from Vietnam and Woodstock to Live Aid. Don’t miss out on this unique treasure.