Key Takeaways:

This story ran in the February 1981 issue of Astronomy in the Gazer’s Gazette section as Alan Goldstein’s first contribution to the magazine. The author revisits the topic in this year’s September issue, available now.

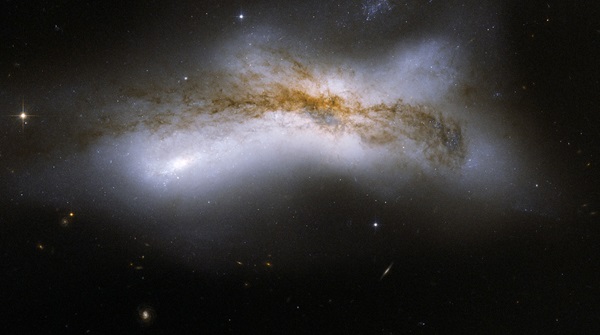

Though technology has changed massively, the thrill of visual observations of peculiar galaxies remains. So, here, we present the original text, alongside photos taken with more modern equipment.

Observing a galaxy is always an exciting experience. You know that the diffuse glow in your eyepiece comes from the combined light of billions of stars organized in a vast cosmic system so distant that its gleam takes millions of years to reach your telescope. Most telescopic observers have examined at least a few galaxies, and those with larger apertures have probably ventured beyond the confines of the Messier list to observe some of the thousands of galaxies listed in the New General Catalogue (see “Observing Galaxies” in Astronomy, April 1980).

But if you find yourself itching for still more cosmic exploration, why not search out a few of the more unusual denizens of our universe: the peculiar galaxies? It has been said that all galaxies are peculiar to some extent, but here we are talking about the truly strange or distorted galaxies — those officially classified as “peculiar.”

What makes a galaxy peculiar?

Spiral galaxies appear to be the most numerous readily observable type of galaxy, with the ellipticals coming in a rather distant second. Although dwarf spheroidal galaxies — like the Sculptor and Fornax Dwarfs — are the most common in the universe as a whole, they are not observable beyond the Local Group. Irregular galaxies make up only three to four percent of known galaxies, and the peculiar galaxies come in at less than one percent. Of course, galaxies that have peculiarities are more common — such as M87, the supergiant elliptical whose famous jet gives it a “p” for “peculiar” in its classification: E0p.

There are a number of things which can give galaxies the distinction of being peculiar — such as:

- strange shapes

- strange halos

- rings

- plumes and tails

- unusual dark lanes

- unusual placement of HII regions

- excessively bright or peculiar nuclei

- apparent explosions

- particularly distorted interactions with other galaxies

- possible interactions with intergalactic clouds of dust or gas.

Some of these — like the last — are extremely rare, but examples of each sort have been observed. And even though all peculiar galaxies are relatively rare, there are quite a few in the Messier catalog. M49 is not generally listed as being peculiar in any way, but it does have a very faint bridge linking it with a tiny irregular galaxy estimated to be about 17th magnitude. M51’s companion, NGC 5195, is a very dusty peculiar galaxy. M64 has an out-of-place dark patch giving it its title of the “Black-eye Galaxy.” M66 is a barred spiral with somewhat asymmetric arms, and M77 is a Seyfert-type galaxy with a brilliant nucleus which seems to be exploding. M101 has very asymmetric arms, as does M106. The exploding M82 with its knotty structure is probably the most famous peculiar galaxy.

Except for the case of galaxies which are obviously involved in a gravitational interaction, the causes of most galactic peculiarities are quite mysterious. For instance, astronomers can’t yet explain why some galaxies seem to be exploding. The same can be said about distorted halos, strange dust lanes, and tails and plumes in seemingly-non-interacting galaxies.

Most rich clusters of galaxies have their share of peculiar galaxies. Some are “in the thick of the action,” where relatively recent interactions with several galaxies may well have caused their present peculiarity, but others are isolated outlying members of the cluster.

Sometimes an explanation is found after intensive study. An excellent example of this is NGC 520, a 13th-magnitude galaxy in Pisces with two tails and a heavy central dust lane. Only within the past few years has its “true” nature come to light. The most recent studies imply that this bizarre galaxy is actually two galaxies, both dusty spirals (like M64 or M90), in the process of colliding.

Since practically every type of galaxy has a peculiar counterpart somewhere else in the universe, it isn’t surprising that a wide variety of peculiarities can occur in any given class of galaxies. While most deep-sky observers know about the jet in M87, they may not have heard of the four jets shooting out of the barred spiral NGC 1097. This discovery adds the small “p” designation to that galaxy’s classification. One jet actually cuts a spiral arm, which in short-exposure photographs can be seen to have “slipped” out of line with the rest of the arm!

What can you see?

Except for some of the brighter peculiar galaxies, most of these objects lack real beauty unless they are currently involved with other galaxies. And since most peculiar galaxies are fainter than 13th magnitude, you will need a large aperture to observe them at all. Still, the mere observation of the target galaxy is often enough for even the most experienced observers.The fact that you have observed a galaxy you know is a celestial oddball can be quite satisfying in itself, and actually seeing the feature which makes the galaxy peculiar is just “icing on the cake.”

The techniques involved in observing peculiar galaxies depend on the type of peculiarity the particular galaxy has. If the galaxy is a face-on spiral, it will be difficult to observe because you are looking through the thin plane of the galaxy. If it is inclined more to our line of sight, it will be easier to observe. The detection of dark lanes is easier than detecting bright areas, unless the bright areas are very bright.

So let’s be honest: Observing the peculiar features visually is generally difficult to impossible. The extended halos which give certain galaxies their peculiar designation require a very large aperture to be observed with any degree of certainty. Extensions, such as tails, are usually too low in surface brightness to be seen with any amateur instrument. Irregular galaxies are generally so thin and diffuse that they are hard to see, so unless the peculiar irregular is bright, you’ll be lucky to see the galaxy at all — much less its peculiarity.

Turning to somewhat more visible features, strange or asymmetric arm structures can sometimes be seen as an uneven hazy patch. If dark patches are large or broad enough, they might be visible in moderate-size telescopes. But bright HII regions have to be of immense size in order to be observable, so you can safely assume that you won’t be able to see most extragalactic HII regions individually. As a chain or large clump, though, these regions of ionized hydrogen will make the glow of the galaxy brighter in that particular area. Explosive galaxies — like the Seyferts — reveal a bright stellar nucleus, and given sufficient aperture, they are among the easiest peculiar features to observe.

Once you have the urge to look for specific peculiarities, the real challenge begins. Is the sky dark and clear enough? Do you have sufficient aperture? Looking for these features might be considered the “ultimate quest” for the serious galaxy observer, but for many these challenges are worth the time and effort.

Challenging the peculiars

NGC 4038/9 is the famous “Ring-tail Galaxy.” A very peculiar galaxy indeed, some astronomers consider it an interacting pair of spiraIs, while others theorize that we are actually seeing a galaxy in the process of splitting in two! The Ring-tail is very bright, and its strange “U” shape is visible in even a 6-inch telescope. This impressive object lies very near NGC 4027, a slightly fainter peculiar galaxy shaped like a hook.

NGC 1961 has recently been identified as the largest known spiral galaxy in the universe, containing some 2 trillion stars in a galaxy 600,000 light-years across. It is also unusual in having a highly asymmetric spiral structure, as if it had interacted with another galaxy, but there are none around. Since the arms are too low in surface brightness to be seen in a 21-inch telescope, their structure seems to be beyond the capability of amateur instruments. But just seeing this cosmic giant is sufficiently appealing.

NGC 3718/29 are a pair of peculiar galaxies found in the same field, both bright enough to be seen with an 8 inch aperture. Whether their peculiarities are caused by a mutual interaction is uncertain, but they don’t appear to be. NGC 3718 has a strangely placed dark lane, which may be visible in moderate-size telescopes. It seems to be arching over the nucleus. NGC 3729’s two peculiarities — an outer ring and a jet — are beyond the reach of amateur telescopes. Still, it’s interesting to find more than one peculiar galaxy in the same field of view.

NGC 5195 is the peculiar companion to the most famous interacting galaxy, M51. It is a small, dusty, and very dense star-city. Visually, this galaxy is bright enough to be seen through small aperture instruments as a roundish patch with a brighter center. With moderately large telescopes, NGC 5195 reveals a bright stellar nucleus. For a challenge, try to see all of the bridge connecting M51 and NGC 5195.

NGC 4861 is an irregular galaxy that contains a semi-nuclear region and a very large emission nebula off to one side. This nebula is rather small and very concentrated. When I first observed this galaxy, I carefully sketched it, unaware of the type of galaxy or peculiarity I was seeing. As it turned out, the sketch made with an 8-inch under excellent skies revealed the nebula as a faint star. Such large HII regions seen at great distances appear nearly stellar.

NGC 5128, also known as Centaurus A, is a bright galaxy which appears as an elliptical. with a large dark lane cutting across it. At −43°, this galaxy is not favorably-placed for observation from the northern United States. With a magnitude of 7.5, it would be one of the most spectacular sights in a small telescope from a Southern Hemisphere location. If you do observe this galaxy, remember that you are looking at the nearest of all double-lobed radio sources, and if your eyes could see radio waves, Centaurus A would appear truly immense, with giant lobes spreading out of the eyepiece field on both sides.

M101 is another of the peculiar Messier galaxies. The arms of this Sc spiral are fairly asymmetric, but for no apparent reason. There are a number of dwarf galaxies in the area, but they just don’t seem large enough to cause the observed distortion. This galaxy is more difficult to see than its magnitude of 8.5 would lead you to believe, because it is face-on to us and has a rather low surface brightness. With moderate-size instruments it appears as a huge roundish patch, but the arms can be glimpsed in large telescopes.

NGC 7727 is one of the brightest galaxies in Aquarius, but its peculiarity is structural. The region of the disk/halo border is strangely shaped, and no one knows why. In this case (as in many others), the interest in observing the object is our knowledge of its mysterious strangeness, since the peculiarities are too faint to see. What sorts of things are going on out there?

Peculiar galaxies may often lack some of the visual excitement of better-known objects, but occasionally they will surprise you by revealing their strangeness. And whether they appear strange through the eyepiece or not, we know that when we observe a peculiar, we are looking at one of the frontiers of modern astronomy. The challenge is there — will you accept it?

Alan Goldstein has been a contributing author since 1981. He also writes about geology, park interpretation, and his first novel in juvenile fiction has just been published.