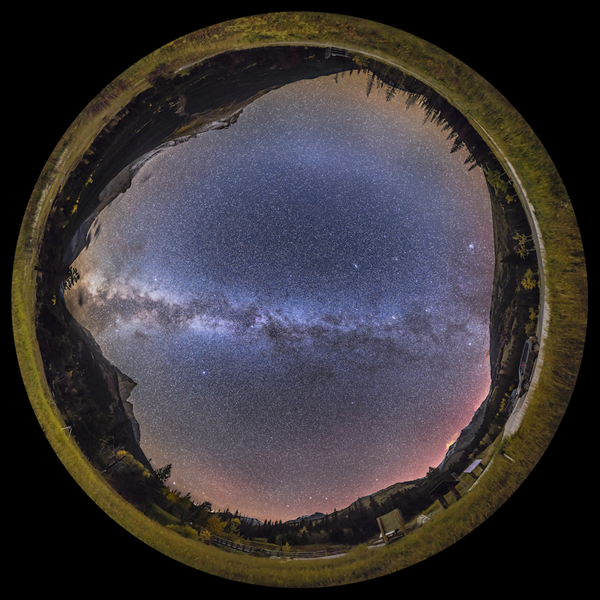

Galaxies are the building blocks of the cosmos, and they are distributed relatively uniformly across the sky. Yes, there are concentrations known as galaxy clusters and there are places that don’t hold many bright examples. But no telescopic fields away from the dense hub of the Milky Way are entirely devoid of galaxies. There are plenty of galaxies “through” or near the Milky Way, too. The problem with viewing the latter group is that it’s not always easy to get a good look at them.

There are three factors that make observing galaxies in and around the band of the Milky Way challenging. First is something called extinction — the dimming of distant objects that occurs when some of their photons are intercepted and absorbed by molecules of interstellar dust. Our galaxy’s central disk is crowded with stars and gas, but it’s the Milky Way’s prolific dust that really makes observing distant galaxies so difficult.

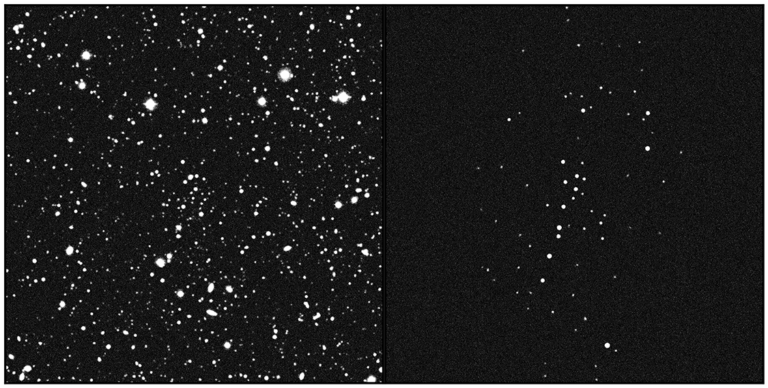

The amount of extinction an observer experiences is directly proportional to how much of the Milky Way they are looking through. Typically, for every kiloparsec (3,262 light-years) of Milky Way your visual path cuts through, the distant object you’re targeting will appear about 1.8 magnitudes fainter. So, in general, the closer a galaxy is positioned to the galactic plane, the dimmer it looks. A distant galaxy near the galactic plane will also appear redder — a phenomenon called reddening — due to blue light being preferentially absorbed and scattered by the Milky Way’s dust. The best examples of this are the extinction-plagued galaxies Maffei 1 and Maffei 2 in Cassiopeia. They are only a few degrees from the galactic plane and were only discovered in 1967 using specialized, hypersensitive photographic plates with the 36-inch Schmidt telescope at Asiago Observatory in Italy.

The third factor is that, by chance, there simply aren’t many intrinsically bright galaxies near our galactic plane. For this reason, galaxy hunters may stay away from the glow of the Milky Way altogether. It’s convenient to observe where the galaxies are most readily abundant and apparent: well above and below the galactic plane. But, eventually, won’t you want to challenge yourself? So why not look for a galaxy where you don’t expect to find one?

None of these recommended targets are easy to observe with small telescopes of roughly 2 to 4 inches in diameter. But most can be seen with an 8-inch scope under night skies that are free of light pollution. This selection is spread over the seasons and spans our Milky Way over many galactic longitudes.

Worthwhile targets

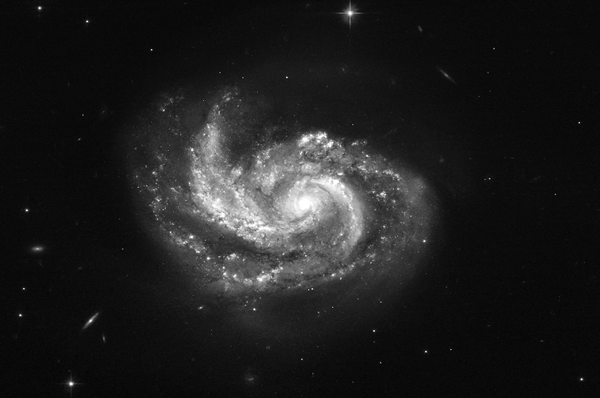

Let’s begin with the brightest: NGC 6946. Sometimes called the Fireworks Galaxy because of its abundance of supernovae, this near-face-on Sc spiral can be a challenge because of its orientation. Face-on means you are seeing the galaxy’s disk from “above,” looking through a thin swath of the galaxy’s stars. But a modest aperture can still reveal NGC 6946’s spiral arms and more subtle features like regions filled with ionized hydrogen (HII regions), which are indicative of massive, young stars nearby. This isn’t the galaxy nearest the galactic plane on our list, so it shows more detail than many others featured here.

The most highly reddened galaxy on this list is the previously mentioned Maffei 1, located only 0.55° from the galactic plane. Astronomers estimate this galaxy suffers from about 4.7 magnitudes of extinction. It is an observing challenge requiring a 12-inch scope and very dark skies. If it were located any farther from the outer rim of the Milky Way, Maffei 1 wouldn’t be visible at all, even in infrared wavelengths.

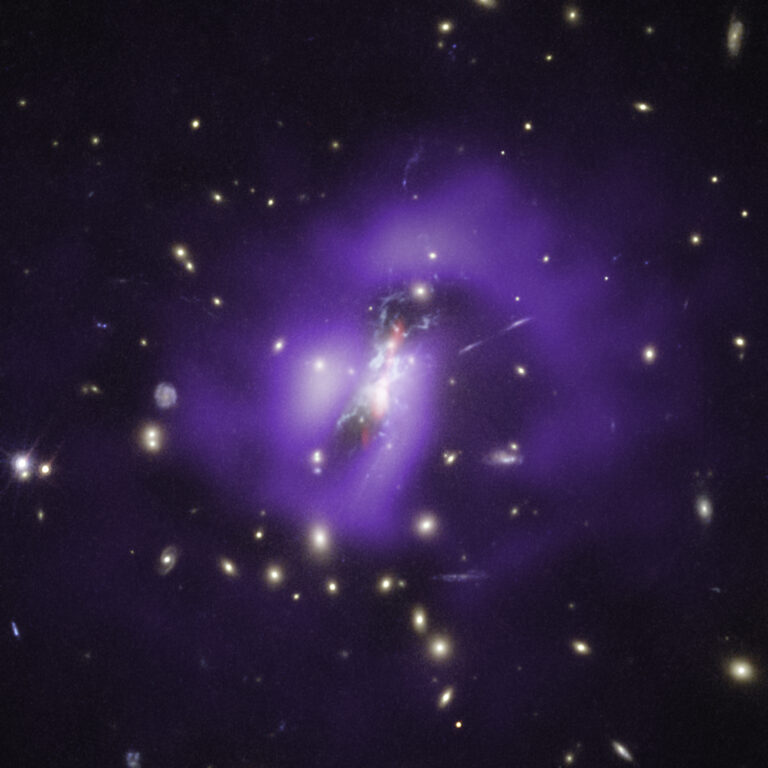

IC 10 is an irregular galaxy in Cassiopeia. A member of the Milky Way’s Local Group of galaxies, it is faint, but bears magnification well. A large telescope will display its patchy nature. IC 10 is the only starburst galaxy in our galactic neighborhood. Like typical irregular galaxies, IC 10 lacks a central hub of older stars, although it has an HII region in its core. Its magnitude of 10.4 makes it sound easier to observe than it is, but with large optics, you can bring out its mottled texture.

A somewhat less challenging galaxy in the compact Milky Way constellation Lacerta is NGC 7231. At magnitude 13, this highly inclined barred spiral is visible using a 6- to 8-inch telescope under dark skies. It is located about 0.3° southwest of a 5th-magnitude field star and about 2° southeast of the large open cluster NGC 7209.

Staying in Cygnus, how many times have you observed the Veil Nebula? Did you know there is a galaxy located only 2° to the Veil’s southeast? NGC 7013 is an edge-on spiral or lenticular galaxy that glows at magnitude 12.4 and spans some 4′. It lies about 2° southeast of NGC 6995. A bright field star resides at its northern end. This obscure object has a compact core, a small hub, and a disk with relatively low surface brightness for an edge-on galaxy.

NGC 6841 is located 4° west-southeast of the large globular cluster M55 in Sagittarius. This relatively obscure elliptical is a small, round, 12.4-magnitude glow that is visible with modest telescopes. With increased aperture (12 inches and larger), make sure to seek out two near-14th-magnitude anonymous galaxies in the same field: ESO 461-24 and ESO 461-25.

Although the winter Milky Way doesn’t have the bright star clouds of Cygnus, Scutum, and Sagittarius, there are plenty of nebulae and clusters to target. Yet, finding galaxies can challenge the northern observer as much as braving the cold weather. Fortunately, a nice pair of faint galaxies resides (appropriately enough) in the constellation Gemini the Twins. NGC 2341 and NGC 2342 are an interacting duo of Sc galaxies that glow at magnitude 13. NGC 2341 has slightly distorted arms and a faint bridge leading toward NGC 2342, which only reveals itself in deep images.

NGC 2380 lies 2° north of Eta (η) Canis Majoris. It is a large class SB0 lenticular galaxy and, at magnitude 11.5, is also relatively bright. Located about 6° south of the galactic equator, NGC 2380 inhabits a rich star field. Look hard for the round hazy patch, as you might mistake it for a planetary nebula in the Milky Way rather than a galaxy located some 70 million light-years beyond it.

What about the lord of the winter sky? Does Orion hold any extragalactic wonders? If you’ve got a telescope of 12 inches or larger, try to find NGC 2119, located about 4.5° north of Betelgeuse. At magnitude 13.6, it’s one of the faintest targets in this article. A highly elongated elliptical galaxy, NGC 2119 is especially noteworthy because of the constellation in which it lies. Capturing it allows you to say, “I observed the most distant object in Orion!”