Key Takeaways:

Before leaving Earth for the International Space Station (ISS) last April, three smartly dressed spacemen — Oleg Novitsky, Pyotr Dubrov, and Mark Vande Hei — took time from their training to pause for a moment of reflection. In the half-gloom of a tiny office in Star City, Russia, they surveyed a faded world map, archaic telephones, and a clock perpetually halted at the instant of its owner’s death. Later, as their greatcoats held back the chill of an early Moscow spring, they laid a splash of red blooms at a grave embedded in the brickwork of the city’s Kremlin Necropolis.

These three spacefarers surely felt the presence of Yuri Gagarin as they paid tribute to that unassuming hero who, 60 years ago, kicked off a space odyssey that will likely never end.

Making a cosmonaut

Gagarin’s upbringing betrayed little of the icon he would become. Born March 9, 1934, into peasant stock in the Russian village of Klushino, his formative years were brutalized by World War II. He learned to read from old military manuals, pestered his father into helping him build miniature gliders, and found work as an apprentice foundryman. A love of aviation ultimately drew him to the Soviet air force, where he flew MiG-15 fighters out of Luostari airbase in Murmansk until he was hired for cosmonaut training in March 1960.

Gagarin excelled in training, exhibiting a sharp memory, quick reactions, and a keen grasp of mathematics. But it was also the ordinariness of this fresh-faced 20-something that helped him win selection as the world’s first space traveler, aboard Vostok 1. Gagarin represented the ideal communist pinup: a humble farm boy who rose up from rags to reach the stars. According to fellow cosmonaut Gherman Titov, the backup pilot for the flight, Gagarin was “a lad who made his dream come true, all by himself.”

Let’s go!

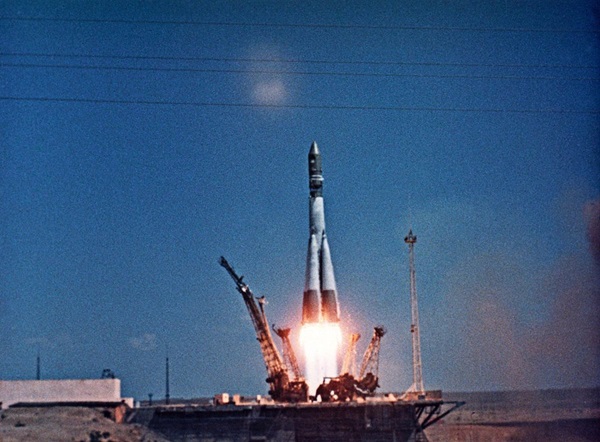

On April 12, 1961, Titov and Gagarin breakfasted on meat puree and toast with blackcurrant jam. They then donned their orange pressure suits and were bused to the Baikonur launchpad on the windswept Central Asian steppe of what is now Kazakhstan. At the launch site, unable to share the Russian going-away tradition of three kisses on alternate cheeks, Gagarin and Titov instead clinked their helmets together in brotherly solidarity.

Inside the spherical cabin of his Vostok capsule, engineers tightened Gagarin’s harness, armed his ejection seat, and fastened his oxygen hose. The spaceship was meant to function autonomously, for fear that separation anxiety from Earth might cause the cosmonaut to go mad once in space. At 9:07 A.M. Moscow Standard Time (MSK), the rocket — a converted R-7 Semyorka intercontinental ballistic missile — roared to life, climbing toward the heavens. “Poyekhali!” Gagarin cried, which translates to “Let’s go!”

Gagarin later recalled “an ever-growing din,” partly muffled by his helmet, as the R-7 climbed higher. The g-forces made speaking difficult. His heart rate soared from 66 to 158 beats per minute. By 9:18 A.M. MSK, he was safely in orbit. Before his eyes, a tiny Russian doll stowed on the spacecraft floated in midair — indicating the onset of weightlessness.

Reaching 203 miles (327 kilometers) in altitude, Gagarin smashed the previous world aviation altitude record of 32 miles (51 km), achieved March 30, 1961, by American Joe Walker in a NASA X-15 rocket-propelled aircraft. As Vostok 1 progressed east, tracking stations across Siberia serenaded him with musical greetings. At the Yelizovo station on the Kamchatka Peninsula, cosmonaut Alexei Leonov was treated to the first crude television image beamed from space. “I could not make out his facial features,” Leonov remembered, “but I could tell from the way he moved that it was Yuri.”

At 9:32 A.M. MSK, as Vostok 1 cut across the South Pacific, Radio Moscow broke the news: “The world’s first spaceship, Vostok, with a man on board, was launched into orbit from the Soviet Union.”

Less than two hours later, Vostok 1 plunged back to Earth. Gagarin ejected from the craft shortly after passing 22,000 feet (6,700 meters), safely parachuting to the ground.

America’s answer

By early 1961, NASA had informed 37-year-old Alan Shepard that he would be the first man in space. He expected to fly in March, but when the chimpanzee Ham narrowly escaped with his life during an unhappy mission in January, it raised eyebrows about the wisdom of such haste to beat the Soviets. An additional uncrewed flight in March assuaged those worries, but at the cost of pushing Shepard’s flight back to May.

Then came Vostok 1. Although U.S. listening posts were already aware of Gagarin’s mission, the tensions of the Cold War meant the announcement that aired April 12 on Radio Moscow still jarred when they heard it. Gagarin’s successful flight meant the U.S. fell another lap behind in the race to conquer space. “We had ’em by the short hairs,” Shepard would repeat to anyone who would listen, following the news, “and we gave it away.”

Shepard was a gruff New Englander and progeny of a wealthy and dedicated military family. His boundless energy had propelled him two grades ahead at school, while an adventurous spirit, keen wit, and a single-minded determination to be the best led the U.S. Navy to handpick Shepard to test its most advanced aircraft.

Chosen as one of NASA’s original Mercury Seven astronauts in 1959, Shepard’s thirst for pushing boundaries would ultimately take him to the Moon. Still, his selection as America’s first space traveler was undoubtedly his proudest accomplishment. “Not because of the fame or the recognition,” Shepard said, “but because America’s best test pilots went through this selection process, down to seven guys, and of those seven, I was the one to go.”

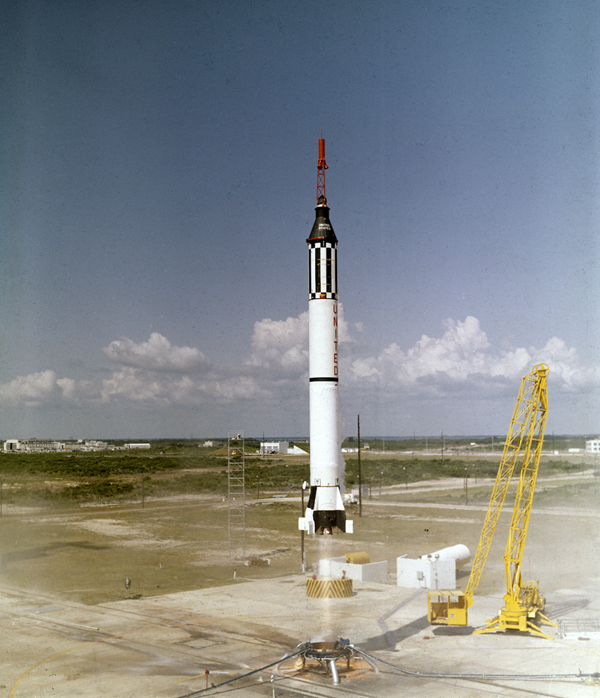

Light this candle

In the predawn darkness of May 5, 1961, Shepard climbed aboard the Freedom 7 capsule at Cape Canaveral’s Pad 5. He knew that truly catching the Russians would take a little time. His 83-foot-tall (25 m) Redstone rocket — a direct descendent of Nazi Germany’s feared V-2 missile — was not powerful enough to achieve orbit, as Vostok 1 had. Instead, it would carry Shepard’s capsule only 116 miles (188 km) into space before splashing down 15 minutes later in the Atlantic Ocean, just north of the Bahamas.

Good fortune did not seem to be on Shepard’s side. Banks of clouds rolling over Florida’s Eastern Seaboard threatened to delay the launch, as did a troublesome power inverter, an unexpected computer glitch, and unacceptably high fuel pressure in the Redstone rocket.

After three hours on his back, Shepard’s morning coffee and orange juice finally caught up with him. “Man, I gotta pee,” he radioed. With only a 15-minute flight planned, a toilet break had gone unanticipated. His request was passed up the chain of command, but Senior Manager Wernher von Braun was emphatic as he instructed fellow mission controllers: “No, the astronaut shall stay in the nose cone!” The message was repeated to the capsule.

Shepard had little choice but to relieve himself in his pressure suit. Engineers temporarily cut the spacecraft’s power — lest he short-circuit the medical wiring or thermometers — so his cotton underwear and Freedom 7’s pure oxygen atmosphere could absorb the result.

The delays were causing frayed nerves across the board. “I’m cooler than you are,” Shepard barked at mission controllers at one stage. “Why don’t you fix your little problem and light this candle?” Those words have since gained immortality, epitomizing the steely nerve of Shepard and his ilk.

At 9:34 A.M. EST, with 45 million Americans watching or listening, Shepard heard the launch command and instinctively reached for the mission timer as the Redstone’s engine breathed fire with 78,000 pounds (35,000 kilograms) of thrust. Although the jolt of liftoff was gentler than he had expected, the astronaut’s heart rate nevertheless jumped from 80 to 126 beats per minute.

“Liftoff,” Shepard yelled, “and the clock is started!”

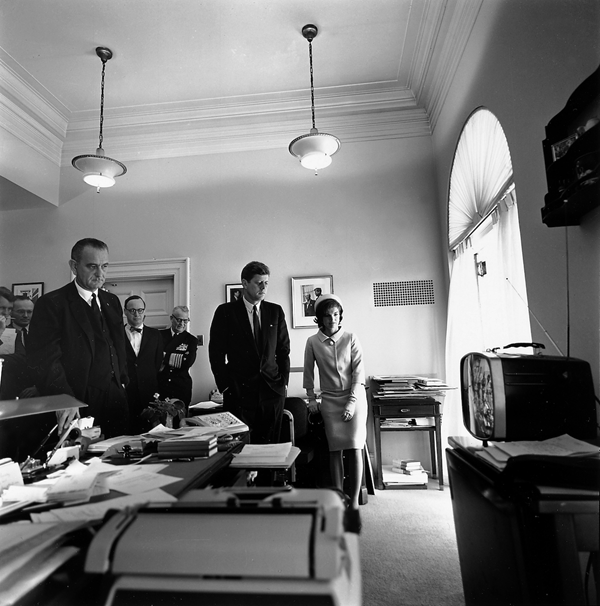

Reactions rippled across the U.S. Taxi drivers pulled over to listen to radio reports of the launch, a Philadelphia judge halted court proceedings, and crowds in Times Square sang and danced. Bars even offered free champagne to revelers. In the White House, President John F. Kennedy stood dumbstruck, his hands shoved deep into his pockets and his eyes fixed on the television picture.

After 80 seconds of flight, the relative calm abruptly morphed into a violent shudder as the Redstone passed through peak aerodynamic turbulence, jackhammering Shepard’s helmeted head against the headrest. But these vibrations quickly ceased. Two minutes after launch, the rocket’s engine shut down as intended, yielding an ethereal silence in the capsule.

Once free of the Redstone, Shepard had only a handful of minutes to test Freedom 7’s systems, twirling his ship through pitch, yaw, and roll axes while travelling at 5,000 mph (8,000 km/h). Weightlessness manifested as floating dust and washers before Shepard’s eyes. But the real spectacle was his view of our home planet itself.

Peering through the capsule’s periscope, Shepard beheld Lake Okeechobee at the northernmost tip of the Everglades, as well as Andros Island, the shoals off Bimini, and the cloud-covered Bahamas. “What a beautiful view,” he declared.

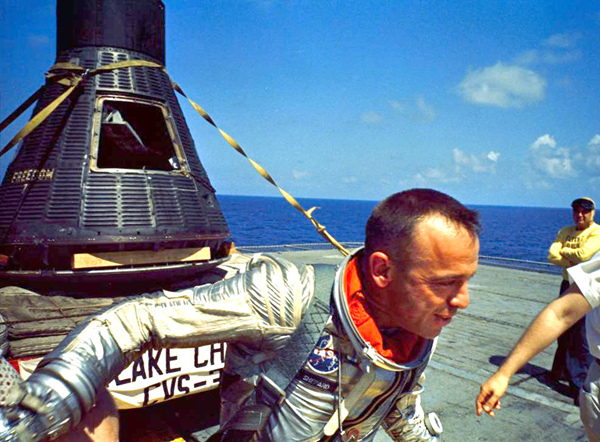

Shepard’s reentry imposed a punishing 11 times the force of terrestrial gravity, briefly leaving him only able to communicate with guttural grunts. Four miles (6.4 km) above the Atlantic, Freedom 7’s drogue parachute deployed, followed by the orange-and-white main canopy. The capsule splashed down within sight of the aircraft carrier USS Lake Champlain. From the deck of the ship, hundreds of sailors applauded America’s newest hero.

A new type of spacecraft

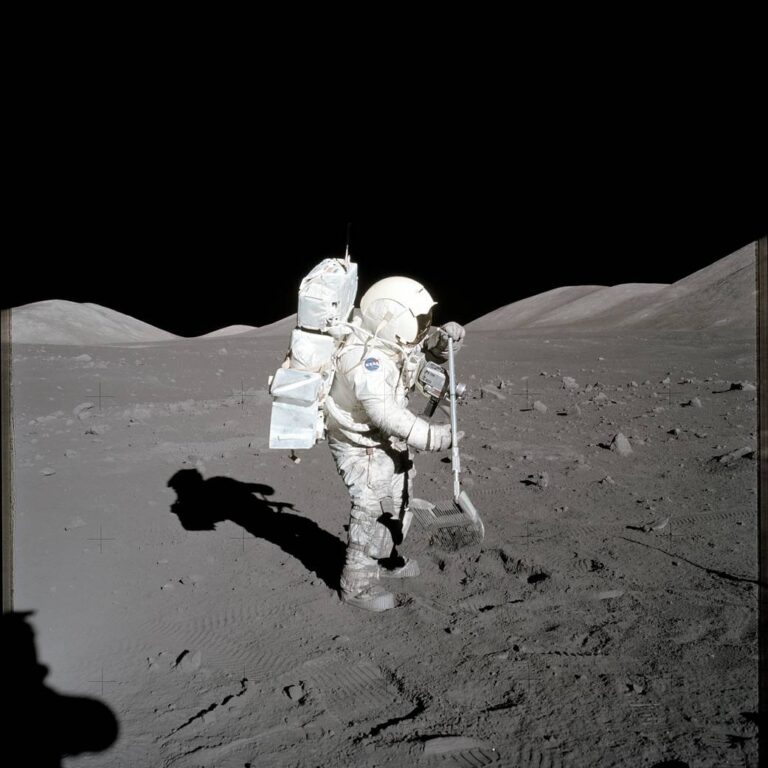

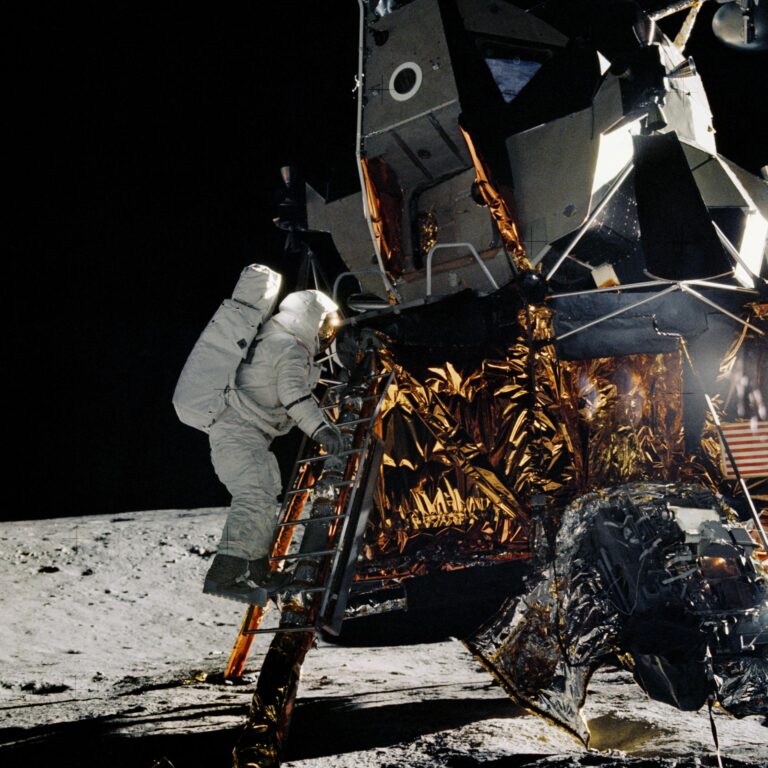

Over the next decade, competition between the U.S. and the Soviet Union continued to heat up. Both sides created enormous rockets to carry human crews to the Moon. When America eventually won the lunar race in July 1969, the Soviets took a new direction: building and occupying the world’s first space stations.

Each victory was hard-won. In 1967, three Americans died in a spacecraft fire on the launchpad, while a Russian was killed when his capsule’s parachute lines became entangled during descent. Three more astronauts narrowly escaped death when an explosion crippled the Moon-bound Apollo 13 spacecraft. In June 1971 — after setting a new world record for the longest space mission — a trio of cosmonauts suffocated when their Soyuz 11 capsule depressurized during reentry.

Against this tortured backdrop was the inescapable truth that exploring space with people was monstrously expensive and difficult. No sooner had Neil Armstrong planted his boots on the Moon’s Sea of Tranquillity than America began looking for a cheaper and more efficient way to send humans to space.

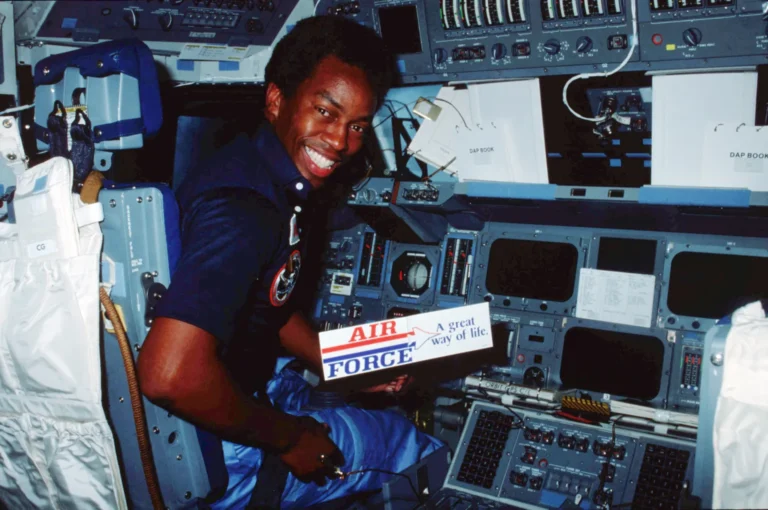

Ultimately, out of a toxic mix of political and military compromise, the space shuttle was born. This new vehicle promised to revolutionize and routinize spaceflight. After rocketing to orbit, it would glide back to Earth, landing on a runway like an airplane.

Bigger dreams — and risks

The maiden voyage of space shuttle Columbia was to be helmed by John Young — America’s premier astronaut and one of only 12 people to walk on the Moon — and co-pilot Robert Crippen. Although eager, Young harbored no illusions about the possibility that he might never return from this first mission of the Space Shuttle Program.

The shuttle was danger on steroids: a delta-winged craft awkwardly bolted astride a fuel-filled external tank and flanked by two solid rocket boosters (SRBs). With no meaningful crew escape mechanism, the shuttle’s ascent profile included several phases, ominously called black zones, in which major emergencies were guaranteed to be fatal.

Ejection seats, parachutes, and pressure suits were available on the first four test flights — STS-1 through STS-4. But these would be phased out for so-called operational missions, starting with STS-5. And ejecting directly into toxic rocket exhaust left Young more than a little skeptical of the escape plans. Even if the astronauts did successfully eject, their parachutes might not open in time to save them.

One afternoon, fellow astronaut Joe Allen bought Young lunch in the cafeteria. When Young promptly attempted to pay him back, Allen laughed and told Young to forget it. “No,” Young retorted. “You don’t go fly these things when you got debts. All my debts are paid.”

The first shuttle flight

Columbia’s first launch attempt on April 10, 1981, was stalled when a timing glitch popped up in one of the shuttle’s computers. The launch was rescheduled for April 12 — coincidentally the 20th anniversary of Gagarin’s Vostok 1 flight.

One minute before launch, Columbia’s three main engines — which blew up with concerning regularity during ground tests — were ready to go as the shuttle’s internal computer took control of the launch sequence.

At T-minus 16 seconds, water flooded the launchpad to reduce the energy reflected up at the shuttle during liftoff. At T-minus 10 seconds, a flurry of sparklers came alive beneath the main engines to burn off residual hydrogen. At T-minus 6.6 seconds, those engines roared to life.

With the engines at full tilt, the countdown hit zero. The SRBs ignited with a dazzling flame and a harsh staccato crackle that shook the 3,500 spectators gathered along the beaches and roadways of Cape Canaveral. Explosive bolts anchoring the behemoth to the pad released at 7 A.M. EDT, allowing 7 million pounds (3.1 million kg) of thrust to loft the shuttle into the sky.

In the cockpit, Young and Crippen felt the vehicle rock back and forth. The incessant vibrations rendered their instruments blurry but still readable. Those vibrations diminished once the boosters fell away and Columbia, powered only by its engines, sailed smoothly into orbit.

Throughout it all, Young’s heart rate climbed no higher than 90 beats per minute, while Crippen’s peaked at almost 130. Young later joked that his old heart simply refused to beat any quicker. Flight Director Neil Hutchinson offered another explanation: The cool, unflappable Young must have been asleep the whole time.

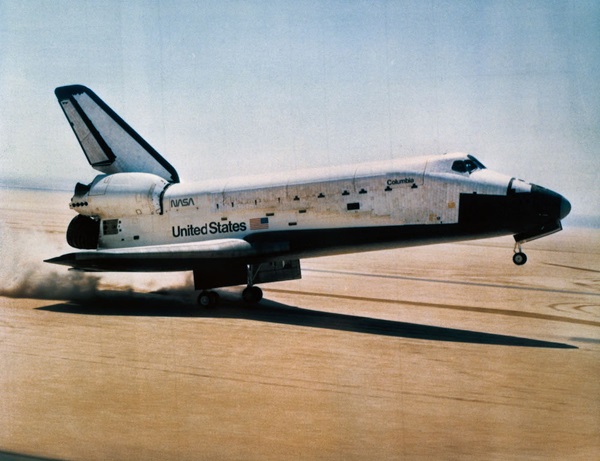

Two days later, Columbia performed a searing hypersonic descent, targeting the runway at Edwards Air Force Base in California. During reentry, temperatures doubled, then tripled, then quadrupled, as ionized gases around the shuttle morphed from salmon pink to reddish orange. The astronauts could only marvel at the hellfire raging inches from their noses. As expected, this plasma sheath around the fast-moving shuttle temporarily severed radio communications. Additionally, a lack of tracking stations meant the shuttle was out of contact for 20 uncomfortable minutes. Once contact was reestablished, Crippen jubilantly remarked, “What a way to come to California.”

For spectators on the ground, more attuned to the serene approaches of commercial jets, the shuttle’s precipitous descent and phenomenal speed caused hearts to pound. Barreling through the sky at an angle some seven times steeper than that of an airliner — and at almost twice the speed — Young pulled back on the stick, morphing the craft from a falling brick into a flying machine of exquisite grace.

At 10:20 A.M. PDT, Columbia touched down at 212 mph (341 km/h), its wheels kicking up a rooster tail of hard-packed sand. As the shuttle came to a halt following a 1.9-mile (3 km) rollout, Young’s characteristic drawl came over the radio: “Do I have to take it to the hangar, Joe?” he asked mission control’s Joe Allen, serving as Entry Capsule Communicator, or CapCom.

Allen chuckled before answering, “We’re gonna dust it off first.”

Stuttering steps

Despite its triumphs, STS-1 was not a perfect success. For example, struts that held Columbia to its fuel tank buckled at liftoff, forcing NASA to strengthen them for future flights. Additionally, several of the shuttle’s thermal tiles suffered damage during ascent and required replacement once back on the ground. (A similar problem doomed Columbia in 2003 when, during launch, a piece of foam fell from the external tank and struck the left wing, damaging the thermal protection system to the point of failure during reentry.)

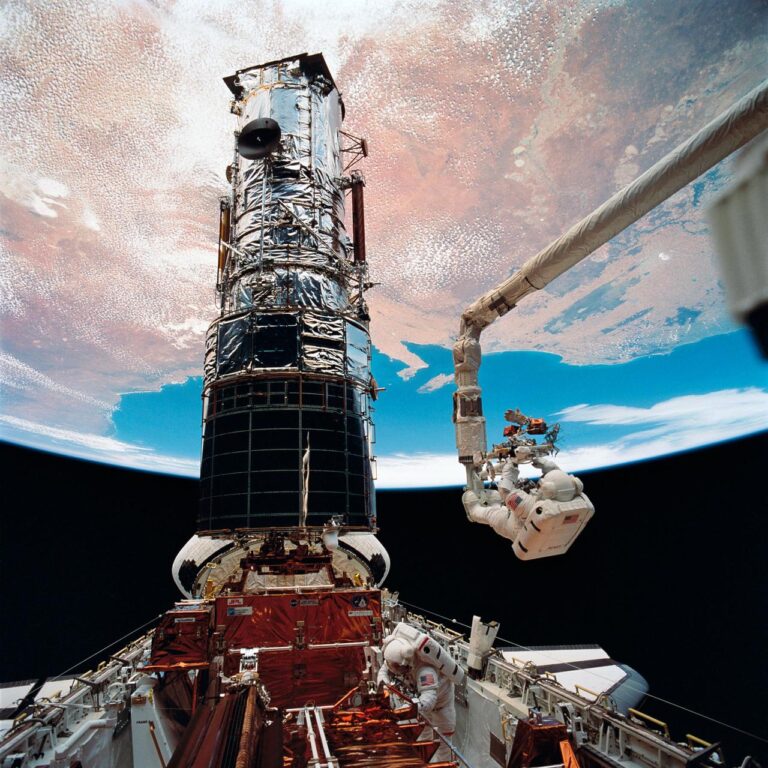

But in April 1981, few foresaw that both Columbia and Challenger would vanish in dreadful tragedies, taking 14 lives. Instead, NASA hoped its planned fleet of at least four reusable shuttles — Atlantis, Challenger, Discovery, and Columbia — would launch weekly with crews of up to seven, allowing more rapid access to space than ever before.

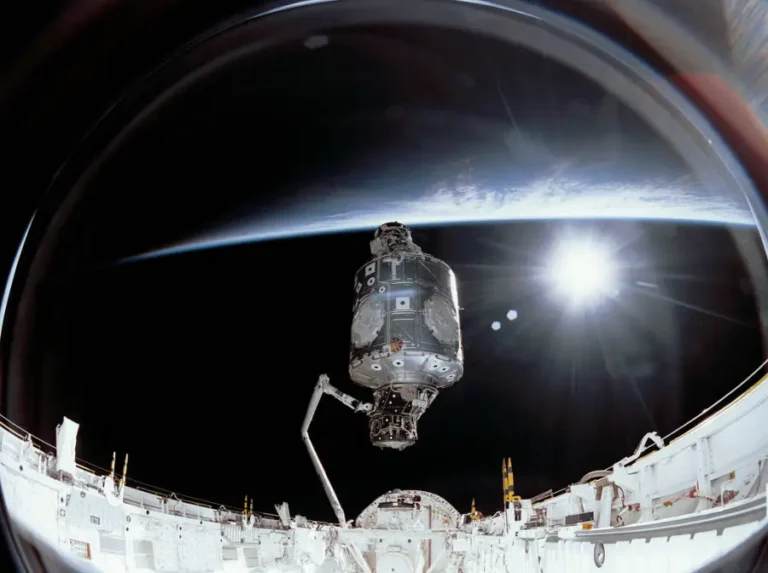

Few also imagined that shuttles would go on to visit Russia’s Mir space station or the ISS after it. And no one dreamed that returning humans to the Moon would use the giant Space Launch System, whose core stage, engines, and boosters draw their design heritage directly from the shuttle.

The last shuttle mission, STS-135, landed July 21, 2011. And though the Space Shuttle Program never quite fulfilled its promise of rapid and routine access to space, it remains an iconic symbol of American high technology.

A new era

Gagarin’s Vostok 1 flight served as a truly transformative moment. Over the next six decades, 504 men and 65 women representing 41 sovereign nations and a half-dozen religious faiths have ventured to space. Twenty-four Apollo astronauts have voyaged to the Moon, with 12 leaving footprints on its dusty surface. And 42 men and women have spent more than a year of their lives in space.

Gagarin himself saw little of this unfolding adventure. Officials barred the highly prized Soviet poster boy from a second spaceflight after the Soyuz 1 crash in 1967 claimed the life of his close friend Vladimir Komarov. Gagarin eventually battled his way back to active status and might have even flown to space again — but before that chance presented itself, he died in an airplane crash in March 1968. He was 34 years old.

Now, the world is launching into a new space race. NASA’s Artemis Program aims to put boots on the Moon by 2024. China and Russia have plans to collaborate on a lunar base later this decade. And later this year, the four crew members of the Inspiration4 mission hope to carry out the first all-civilian spaceflight inside a SpaceX Crew Dragon capsule.

Also chomping at the bit to dominate the suborbital market is Blue Origin, whose reusable New Shepard rocket and six-seat crew module sent four civilian astronauts to the edge of space July 20. Similarly, Virgin Galactic’s successful July 11 SpaceShipTwo flight brings it ever nearer to making suborbital tourism a reality, aiming to commence commercial operations in the latter half of 2022. And Houston-based Axiom is planning private missions and add-on modules to the ISS beginning in the next few years.

At Boca Chica in Texas, meanwhile, SpaceX continues to test its giant Starship, recently selected by NASA to return humans to the lunar surface for the first time since 1972. And the dearMoon project hopes to see the first lunar tourists fly around Luna — à la Apollo 8 — aboard a SpaceX Starship in just two years’ time.

The future of spaceflight seems brighter than ever, if we’re willing to embrace it. As Gagarin, the man who started it all, said: Poyekhali! Let’s go!