Key Takeaways:

- The Antikythera mechanism, a first-century BC Greek device recovered from a shipwreck, is an analog computer designed to track and predict celestial movements, including the phases and orbit of the Moon, the position of the Sun, and the occurrence of eclipses.

- Employing at least 27 gears (possibly more), the mechanism incorporates gear ratios corresponding to known astronomical cycles such as the Metonic cycle (19 years) and the Saros cycle (18 years), enabling the prediction of lunar and solar eclipses.

- Inscriptions on the mechanism's bronze plates include Greek text relating to celestial bodies and calendar systems, suggesting its use in tracking religious ceremonies, festivals, and sporting events, indicating a connection to northwest Greece.

- While its precise origin and creator remain unknown, its existence points to a sophisticated level of astronomical and mechanical knowledge in ancient Greece, predating comparable devices by approximately 1,500 years.

Many amateur astronomers know the familiar thrum of small motors guiding an automated telescope under a tranquil night sky. Powered by a computer within a plastic box attached to the scope, this technology allows for the quick and accurate targeting of thousands of popular celestial objects. It’s almost like having the cosmos in a box.

Although it may seem that the ability to use a computer to track the Moon, planets, and stars is a modern development, in reality, it dates back at least two millennia. In what must have been a collaboration between an astronomer-mathematician and a master craftsman, an ancient analog device was built that could track the heavens. Now known as the Antikythera mechanism, its creators designed it to capture the known cosmos in a wood and bronze container about the size of a shoebox.

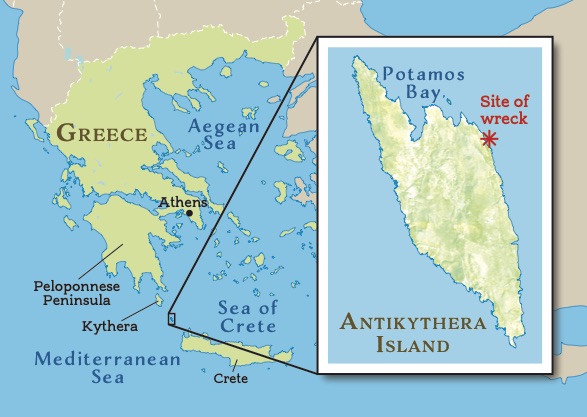

In the first century b.c., a massive Roman cargo ship was caught in a storm near an island now called Antikythera. Located at the edge of the Aegean Sea, about halfway between southern Greece’s Peloponnese peninsula to the north and Crete to the south, this island was the only place to seek safety. The ship, bound for Rome, was more than 150 feet (46 meters) long and built to carry grain. But on that day, it was stocked with treasure and plunder from across the Greek world. As the storm pummeled the vessel, it began to sink. The crew abandoned ship; not everyone survived. By the time the weather finally eased, the ship, along with its precious cargo, was lost.

At least, it was lost until the spring of 1900, when a similar storm likewise forced a small Greek boat to seek shelter near Antikythera’s shores. But this vessel and its crew of sponge divers survived. Once the seas were calm, one of the divers, wearing a bulky dive suit and copper helmet, slipped over the edge of his ship. He quickly returned with an amazing discovery. The seafloor was littered with pieces of bronze and marble statues. Soon after, a nine-month salvage operation kicked off. Salvagers eventually recovered thousands of broken and fragmented objects. Among these treasures was an unappealing lump of corroded bronze presumed to be part of a statue. It was so mundane, in fact, it was almost tossed back into the water.

The recovered items were sent to the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. In 1902, investigators examined pieces of the corroded bronze artifact. They noticed Greek writing and intermeshed gears. The “discovery” was soon reported to the local newspaper, putting a century-long investigation into motion.

Early investigators assumed the Antikythera mechanism was some sort of clock, calculating device, or navigational instrument of Greek origin. Along with clearly corroded gears, they noted several Greek inscriptions. One bit of text reading “Rays of the Sun” clearly hinted at a celestial connection, but many questions remained. What was such a device doing on a 2,000-year-old ship? What was its purpose? And who could have constructed such a seemingly complex object a millennium before such geared devices were commonplace? Academics struggled in vain to answer these queries for years — until 21st-century technology revealed the marvels of this astronomical artifact.

Solving a mystery

From the 1950s to his death in 1983, English physicist Derek J. de Solla Price carefully studied the fragments of the Antikythera mechanism. Using radiograph X-ray imaging, he examined the subtle details of the device’s two main gears. But he also counted an additional 25 gears, making it quite complex. (For comparison, a typical grandfather clock has 11 or 12 gears.) The two largest gears appeared to have 235 teeth and 127 teeth, respectively. Price consulted with mathematician Otto Neugebauer, who identified these teeth counts as relating to the celestial cycles of the Moon.

Isaac Newton reportedly said calculating the motion of the Moon was the only thing that gave him a headache. Indeed, Luna’s movement is extremely complicated. The ancient Greeks, as well as many other cultures, used the phases of the Moon to set their calendars. This lunar cycle — lasting from Full Moon to Full Moon — also served as the basis for many religious and ceremonial events. But the Sun was used to determine the calendar year, and breaking a roughly 365-day year into 12 lunar cycles spread over some 354 days represented a real challenge.

The Moon’s orbit around the Earth can be measured two different ways. The Moon moves against the backdrop of stars along the path of the ecliptic (the plane of the solar system). The time it takes the Moon to make one full circuit, returning to the same set of stars where it previously appeared, takes 27.3 days. This is known as the sidereal month. But due to the simultaneous motion of Earth around the Sun, the time required for the Moon to cycle from one Full Moon to the next is 29.5 days, or one synodic month. It is the synodic cycle that played a major role in setting calendars, marking festivals and religious ceremonies alike.

Neugebauer suggested that the tooth count on the two large gears could be related to these well-known long-term cycles of the Moon. The 235-toothed gear appeared to precisely match up with the 235-month (19-year) Metonic cycle of synodic months. This cycle dates back to hundreds of years before the rise of Greek culture, when Babylonian astronomers realized the same phases of the Moon will reoccur on the same dates of the solar year against the same backdrops of stars once every 19 years. This knowledge became vital to keeping the lunar calendar in sync with the solar year.

Trying to perfectly fit 12 synodic lunar months into a solar year is impossible, however. A dozen synodic months adds up to 354 days, which is 11 days short of the roughly 365-day solar year. A strictly lunar calendar would very quickly fall out of step with the seasons. But since the 19-year Metonic cycle contains almost exactly 235 synodic months, it allows celestial trackers to align these two very important ways of measuring time. In other words, the 235-tooth gear could have been used to precisely track the Metonic cycle.

But the 127-tooth gear still presented a mystery — that is, until Price realized that 127 multiplied by two is 254, another number related to the Moon. In the 19-year Metonic cycle, there are 235 synodic lunar months, but 254 sidereal lunar months. Therefore, they concluded, the Antikythera mechanism was likely used to track both the phases and the orbit of the Moon.

Price also examined the device’s front plate. With only a small portion of the dial intact, he counted what visible markings he could on the circular scale. He found the inner scale appeared to have 12 divisions, as well the Greek word for “claw,” a possible reference to the constellation Scorpio. Other letters, Price found, suggested the scale was also inscribed with the Greek word for Virgo.

The outer portion of the scale, on the other hand, was divided into 365 sections. Based on the markings and words Price observed, he speculated the front dial tracked the movement of the Sun. Some have even suggested that there were moving pointers dedicated to the five visible planets, which would make the Antikythera mechanism an orrery or planetarium. Modern reconstructions have often incorporated these ideas with some moderate success.

Treasures speckle the shipwreck

The Antikythera mechanism is far from the only precious artifact found at the site of an ancient shipwreck that occurred off the coast of a small Greek island some 2,000 years ago. In addition to skeletal human remains, researchers have uncovered remnants of dozens of bronze and marble statues, as well as personal belongings such as gold earrings, silver coins, ornate glassware, pottery, and jewelry.

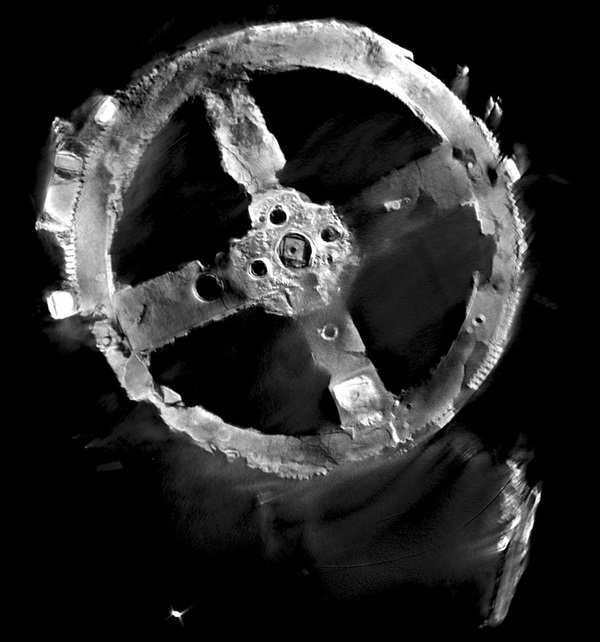

As part of the Return to Antikythera Expedition in 2017, for example, experts from the Greek Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities and Lund University in Sweden spent more than half a month exploring the underwater archaeological site. Of their many finds was the bronze arm seen in the image above, which presumably broke off a larger statue during the initial shipwreck. After being submerged in salty seawater for some two millennia, the disembodied arm is unsurprisingly rusted, but it’s also still in relatively good shape.

Although researchers excavated the bronze arm, they suspect many more artifacts like it are still buried beneath boulders on the seafloor. Only time will tell what other treasures are patiently waiting in those watery depths. — Jake Parks

These detailed images of various pieces of the Antikythera mechanism were assembled using data collected in 2005. The top row views relied on the technique of polynomial texture mapping (imaging objects under varying lighting conditions to bring out surface features). The bottom row views were created using high-resolution microfocus X-ray computed tomography, or X-ray CT.

Diving deeper

In 2005, a group of mathematicians, astronomers, and historians in Greece, the U.K., and the U.S. first formed the Antikythera Mechanism Research Project. Their goal was to reexamine the artifact with 21st-century technology. Using a purpose-built 3D X-ray machine, they were able to visually move, layer by layer, through the corroded bronze. The team thinks they’ve confirmed the 27 gears Price had previously counted, and possibly found evidence for several more.

One smaller gear on the back of the device was particularly puzzling, though. Price had examined this gear and determined it may have had 222 or 223 teeth, and the research team confirmed the latter count. Lo and behold, here was yet another number related to the Moon’s motion.

Eclipses, whether lunar or solar, are beautiful and inspiring events. But for the ancients, they were also packed with power and meaning, which is why predicting them was so important. Babylonian astronomers discovered that both lunar and solar eclipses occur in a repeating 18-year pattern. The Saros cycle of eclipses, as it is known, consists of 223 synodic lunar months. So, every 18 years, the Sun and Moon will align again at roughly the same time and position in the sky (though the region on Earth where the eclipse is visible varies). Therefore, understanding the Saros cycle was a powerful tool for presaging future eclipses. The Antikythera mechanism, it seems, was an analog computer designed to perform exactly this task.

The ancient eclipse calculator was encased front and back with bronze plates which were inscribed with Greek letters and what appeared to be curved scales. However, corrosion made early attempts to decipher the markings difficult. Price was more successful, finding the back plate covered in what appeared to be instructions for how to use it. He also suspected the incised lines represented scales to provide output information as the gears were turned. But due to damage to the back plate, Price was unable to decipher the lines’ exact nature or purpose.

In 2005, the lead researcher of the Antikythera Mechanism Research Project, Tony Freeth of University College, London, took a crack at the problem — and it relied on a small piece dubbed fragment F at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. New 3D images showed that this part made up the lower section of the back plate. Freeth also noted the continuation of curved lines, which were part of a larger spiral, as well as additional inscriptions. With intense effort, he was able to identify markings that referred to the Moon and the Sun, and the Greek symbol meaning “hour.” The spiral dial was used to predict solar and lunar eclipses. The Antikythera mechanism’s gears drove a pointer that would tell the user the date and even the time of upcoming eclipses.

Based on what Price found before his death in 1983, he had declared that the Antikythera mechanism was the world’s first analog computer. At that point, he lacked a lot of evidence to back up the claim. But thanks to the intense efforts of the Antikythera Mechanism Research Project team, as well as Freeth’s relentless detective work, it’s now clear that Price had it right all along.

Uncertain origins

While we now have a general understanding of how this ingenious device worked, who made it and how it came to be aboard that doomed Roman cargo ship remains more mysterious — although we do have some hints.

In 1976, explorer and diver Jacques Cousteau reexamined the Antikythera site. He and his crew made many discoveries, providing clues to the origins and date of the ship that carried the mechanism. Cousteau recovered a handful of silver and bronze coins from Pergamon in Asia Minor that dated back to 65 to 50 b.c.

Wine jars known as amphora were also recovered, and the style of the jars indicated that they were made in Rhodes and on the island of Kos. The amphoras dated back to around 70 to 60 b.c. Based partly on this evidence, many researchers assume this cargo ship was carrying treasure that originated in the eastern provinces of the Roman Empire. But that still doesn’t shed light on whether the Antikythera mechanism was captured loot or a purchase for a wealthy Roman intellectual.

The individual who commissioned the mechanism will likely always remain a mystery, as will the craftsman who built it. But there are clues inscribed on the bronze plates that can help reveal the society that devised such a device. In the ancient world, calendars were far from uniform. And based on the names of months and festival designations inscribed on its bronze plates and dials, the Antikythera mechanism likely was born somewhere in northwest Greece.

In this region was the island of Rhodes — home to the astronomer Hipparcus (190–120 b.c.) and his successor Posidonis (135–51 b.c.) at the time of their deaths. The Antikythera mechanism was likely made around the time that Posidonis was teaching and traveling across the Roman world. The Roman senator and contemporary of Julius Caesar, Cicero (106–43 b.c.), even once mentioned the home of a prominent Roman containing what may have been an orrery or planetarium device made by Posidonis. This brief allusion tells us that the Antikythera mechanism was perhaps just one example of many similar devices that existed throughout the ancient world at the time.

For example, at the base of the ancient Acropolis in Athens, Greece, stands the Tower of the Winds. Constructed at about the same time as the Antikythera mechanism, this tower served both meteorological and time-keeping functions. And to do that, it relied on sundials, wind vanes, and even a geared water clock. The first-century Greek inventor Hero of Alexandria developed even more complicated devices than the Tower of Winds, too, including steam engines, the first vending machine, a wind-powered organ, automatic doors, and much more. The Greek and Roman world was alive with ideas, inventions, and creativity at this point in history. Although the Antikythera mechanism has long been considered an advanced anomaly, in fact, it was part of a thriving tradition of innovation.

The Antikythera mechanism could calculate 42 separate calendar functions, predict the motion of the Moon, the positions of planets, and the timing of lunar and solar eclipses. It helped track religious ceremonies, festivals, and the Greek Panhellenic games, as well as other sporting events. And it did this all roughly 1,500 years before another comparable device was known to exist. Using only astronomy, mathematics, and simple tools, the Antikythera mechanism truly capture the cosmos — and Greek culture — in a box.