Key Takeaways:

- The discovery of Neptune, while often presented as a triumph of Newtonian mechanics, involved significant complexities, including overlooked prior observations of Uranus and multiple failed attempts at prediction by various astronomers.

- Both John Couch Adams and Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier independently calculated Neptune's approximate position based on discrepancies in Uranus' orbit, though neither initially led to a successful observation.

- Johann Galle and Heinrich Louis d'Arrest ultimately discovered Neptune based on Le Verrier's refined prediction, using a recently published star chart to identify the planet's location.

- Subsequent analysis revealed that the accuracy of Adams' and Le Verrier's predictions was partly due to fortunate coincidences, particularly related to the near 2:1 orbital resonance between Uranus and Neptune, and incomplete understanding of perturbation theory.

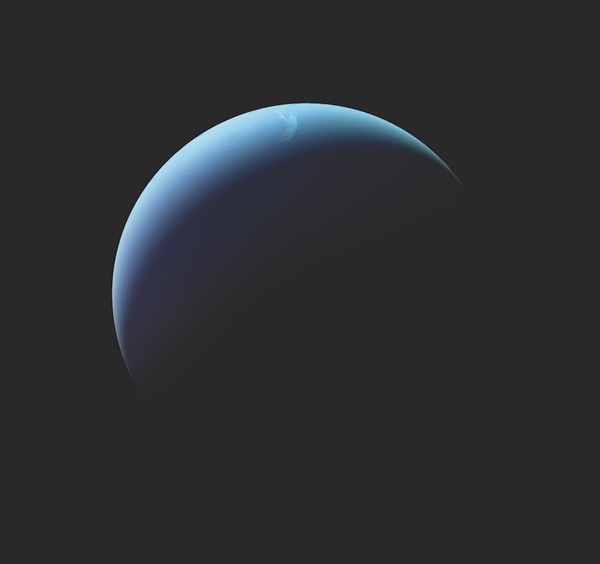

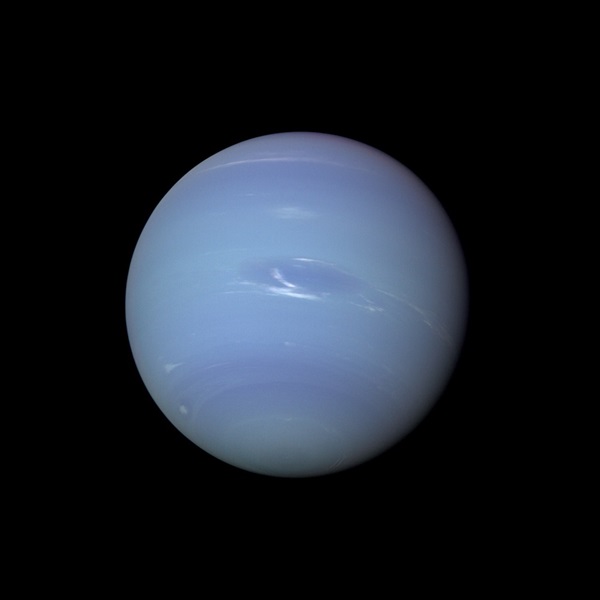

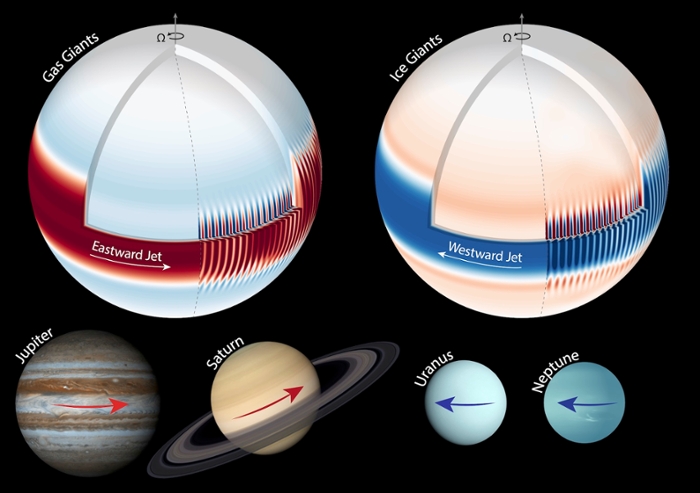

The story of how observers discovered Uranus and Neptune is among the most celebrated in the annals of astronomy. As the first modern additions to the solar system, joining the classical planets known to the ancients, the ice giants forever changed our conception of the universe. And the discovery of Neptune was an inspiring testament to the scientific method: A mysterious discrepancy between observation and theory led to a prediction that was validated in dramatic, cosmos-shattering fashion.

At least, that’s how the story usually goes. But finding Neptune was less straightforward than the story suggests. It’s a tale filled with fascinating characters, missed opportunities, and even international intrigue. And in the end, the entire discovery hinged on a crucial bit of luck that went unnoticed for nearly 150 years.

A discovery re-discovered

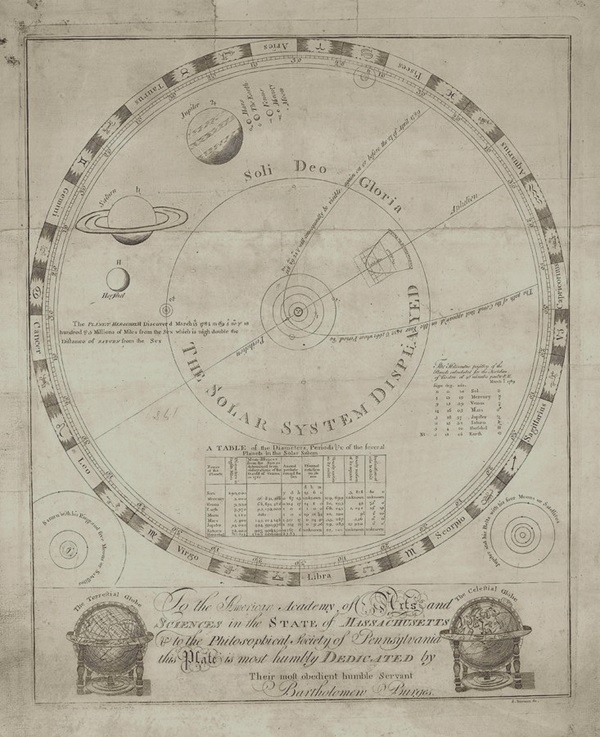

It’s easy to forget that for most of the 18th century, the solar system was a remarkably simple and straightforward place (which certainly made orrery-makers’ jobs easier). There was the Sun, the seven planets including Earth, our Moon, the four moons of Jupiter, the five moons of Saturn, and a few periodic comets. The zone between Mars and Jupiter, soon to fill in with asteroids, was still empty. The entire outer solar system beyond Saturn and below the sphere of the fixed stars was devoid of features, as it had been since Aristotle’s time. And all the solar system’s bodies moved tidily and predictably according to Newton’s law of gravity.

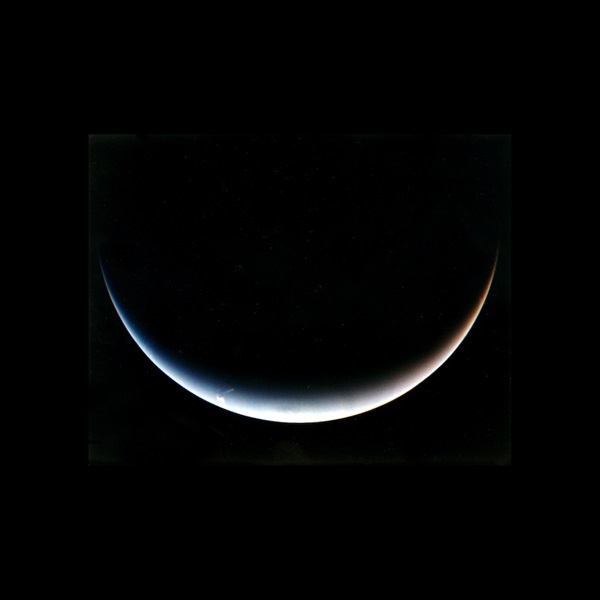

But this ancient, elegant picture was shattered by William Herschel’s serendipitous discovery of Uranus in March 1781. And that was just the beginning when it came to shaking up the solar system: The new planet’s orbit obstinately refused to follow the path mathematicians insisted it should, pointing to another hidden planet lurking beyond.

In 1821, a now largely forgotten French astronomer named Alexis Bouvard published tables of Uranus’ motion, over which he had toiled for many years. Bouvard was a shepherd boy who rose, improbably, to become director of the Paris Observatory. He was attempting to combine

pre-discovery observations of Uranus from star catalogs (the earliest was from 1690) with the presumably far more accurate observations made since Herschel uncovered the world.

But he couldn’t do it. He discarded the older observations, and for a moment, Uranus’ observed motion seemed to be reconciled with theory. However, soon it was off course again. Before 1821, Uranus appeared to be moving faster than it should have been, based on the known bodies near it. But within a few years, it appeared to be moving too slowly. Bouvard himself suspected an unknown planet might be the cause, yet he did nothing to follow up.

Seeking the answer

Over the years, the nagging difficulty of explaining the future path of Uranus only got worse. Eventually, two mathematical astronomers began to investigate.

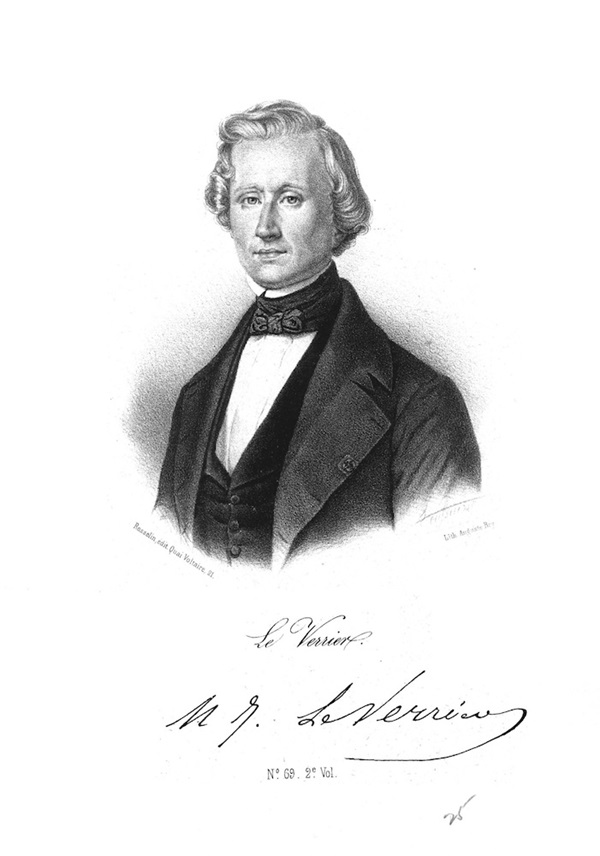

One was John Couch Adams, a native of Cornwall. Adams took nearly all the prizes in mathematics as an undergraduate at St. John’s College, Cambridge, and was awarded a fellowship. The other was Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier of France, a répétiteur (private tutor or assistant teacher) at the École Polytechnique who devoted most of his time to researching celestial mechanics.

Adams got interested in the Uranus problem on his own, sketching his first plan to investigate as an undergraduate in 1841. Le Verrier, having already published important work on the stability of the solar system, was instead drafted onto the job during the summer of 1845 by the then-director of the Paris Observatory, François Arago. Arago had become frustrated by the lack of progress being made on the theory of Uranus by Eugène Bouvard, Alexis’ nephew, who had been assigned the investigation after Alexis retired.

Few people are familiar with the intricacies of classical celestial mechanics anymore. And hardly anyone undertakes the incredibly long calculations with pencil and paper that were once required. Moreover, the prolonged concentration needed for such calculations feels quaint in an age of constant internet and media buzz. As a result, it is a bit difficult today to imagine just how challenging was the problem Adams and Le Verrier set for themselves.

It had, of course, always been mathematical astronomers’ jobs to make predictions. They used Kepler’s laws to predict planets’ future positions given elements of their elliptical orbits, and applied Newton’s theory of gravitation to Keplerian elliptical motion to account for perturbations due to other planets. All of this was very complicated and tedious, but fairly straightforward, provided that one had accurate orbital elements and that the desired prediction wasn’t too far into the future. (Even with a supercomputer, the long-term effects of three-body interactions soon get very ugly.)

In searching for the distant planet, however, Adams and Le Verrier had to reverse-engineer the operations. Instead of starting with Uranus’ orbital elements and computing the motions of the unknown perturber, they had to start with Uranus’ motions and try to firmly pin down the orbital elements that explained them. “Doing multi-parameter minimization, which is what they were trying to do, is no easy task, especially if you don’t have a computer,” says Greg Laughlin, an astronomer at Yale University and an expert in numerical simulations.

Luckily, Adams and Le Verrier were up to the task, albeit in their own eccentric ways. Adams was extraordinarily conscientious in both his studies and tutorial responsibilities, permitting himself to indulge his Uranus hobby only during vacations. He was also capable of carrying out long and tedious calculations in his head without missing a beat, as was Le Verrier.

Using data on the observed motion of Uranus obtained from the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, Adams attempted to use the unknown planet hypothesis to reconcile observation with theory. In the end, Adams carried out six calculations using different hypotheses. His first two calculations used the simplifying assumption of a circular orbit. And all but the last relied on the semi-empirical Bode’s law — which predicted that each planet (moving outward) should be about twice as far from the Sun as the last — to determine the supposed world’s mean distance.

He finished his most accurate calculations in September 1845 and made slight corrections the following month. These gave theoretical positions for the presumed planet. As it would turn out, they were only off by a quite searchable 2° on either side of where Neptune really was at the time. Still, no one searched for the new world.

Adams communicated his first result to his overworked teacher and director of the Cambridge Observatory, James Challis. Having mountains of other work piled on his desk, Challis did what any overextended person would do: He suggested Adams take his ideas up the ladder to a higher authority.

That authority was the Astronomer Royal, George Biddell Airy. With a letter of introduction to Airy but no formal appointment, Adams attempted to pay Airy an unannounced visit. Adams attempted three total visits, once on the way to, and twice returning from, a vacation in Cornwall. Airy was home, but did not receive Adams, so Adams left a note. To the Astronomer Royal’s credit, Airy did follow up with a response letter, in which he posed to Adams a rather technical question.

Adams never replied. The late astronomy historian Craig Waff did discover during a visit to the Truro Records office in 2004 that Adams had begun to draft a letter back to Airy. The reason it wasn’t sent will likely never be known; perhaps it was merely a matter of becoming absorbed with other duties, with a chaser dose of procrastination. As always in the course of history, the discovery story of Neptune includes a trail of wistful what-might-have-beens.

The discovery in Berlin

Except for a few further computations made at the end of 1845, Adams laid the Uranus problem aside for a time. In early 1846, he started helping Challis compute comet orbits from Challis’ backlog of observations. The initiative to explain the orbit of Uranus fell on Le Verrier and the French.

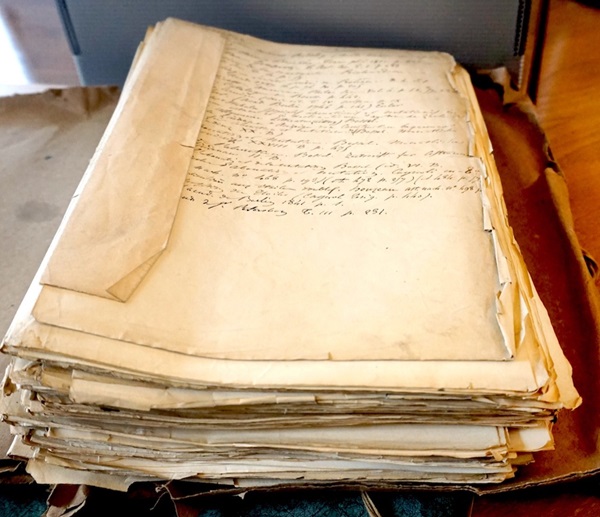

Le Verrier attacked the problem with his considerable computational abilities. He was “a calculating machine,” says Guy Bertrand, a graduate student at Paris Observatory. “He double-checked every calculation and did a lot of them mentally.” For his Ph.D. dissertation, Bertrand is reconstructing all of Le Verrier’s calculations — no small feat, considering he published only brief summaries of them. “There are thousands of these scraps of paper,” says Bertrand. “In all these pages, I found hardly any errors.”

On June 1, 1846, Le Verrier announced his results so far, and included a position for the planet that, as Airy recognized immediately, was close to the location that Adams had proposed the previous autumn. Airy saw an opportunity and used his influence to get Challis to search that region of the sky at Cambridge University Observatory using the 11.6-inch Northumberland refractor.

Challis obliged, and started a thorough if rather plodding hunt, which would have led to the discovery of the planet eventually. Indeed, he even recorded Neptune twice in early August, but did not get around to comparing its changing position between observations. Science historians have often criticized Challis as a bumbler, but he was at least looking.

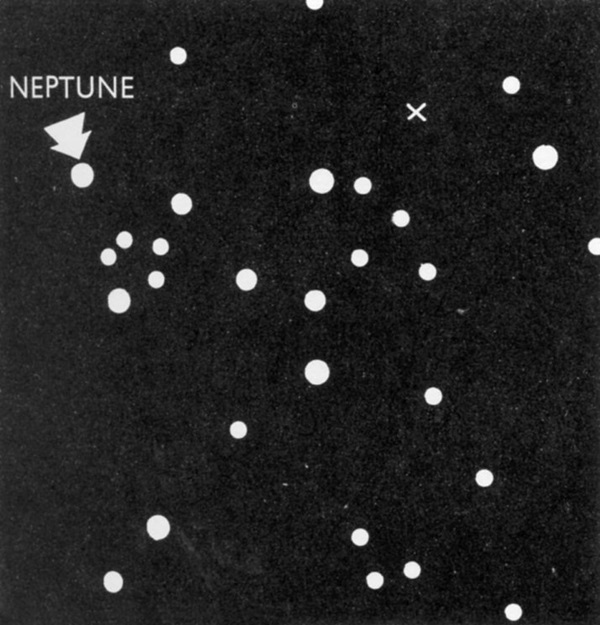

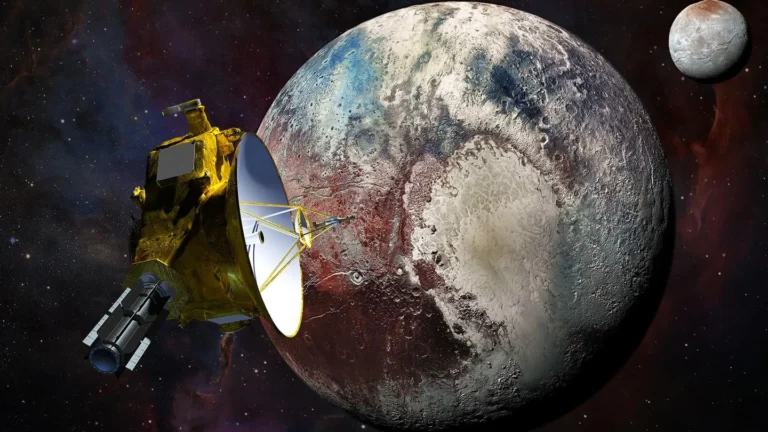

In France, meanwhile, Le Verrier encountered nothing but apathy. Finally, after he published a new calculation that put the planet just over a degree from where it actually was, and made a new pitch for astronomers to seek it out, Le Verrier found his man. Or rather men. They were Johann Galle, an astronomer at Berlin Observatory, and a student named Heinrich Louis d’Arrest, who suggested using a star map just published in Berlin that was not yet distributed to astronomers elsewhere to aid in their search.

After an hour’s work at the telescope on Sept. 23, 1846, with Galle calling out the positions of stars in the field and d’Arrest checking them on the map, one finally elicited the exclamation: “That star is not on the map!” Close scrutiny revealed the aquamarine world’s disc, of which Galle said, “My God in heaven, that’s a big fellow!” And so it was — a planet nearly the same size as Uranus and the last giant to be added to our solar system.

An international furor

The post-discovery history of Neptune is nearly as interesting as the find itself. The early efforts of Adams and Challis’ unavailing search came to light and provoked what threatened to be an international incident during a time of strained British-French relations. This was resolved with Le Verrier and Adams both receiving shares of the credit. A few historians have claimed there was a British conspiracy to doctor the documents in order to steal credit from the French. But there is no evidence of this at all.

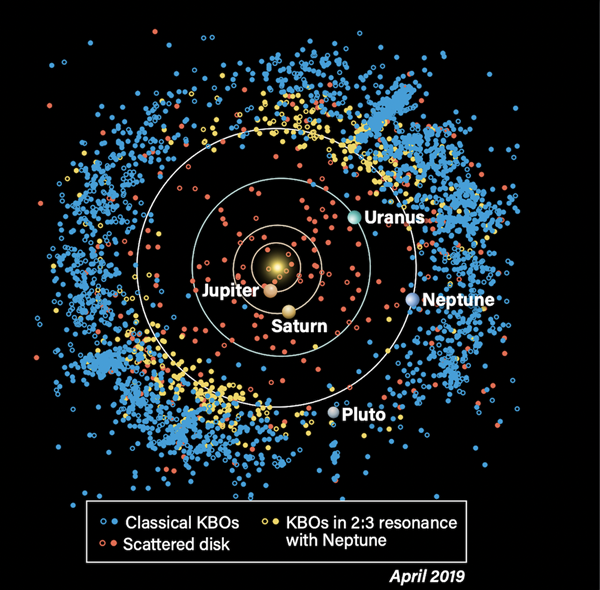

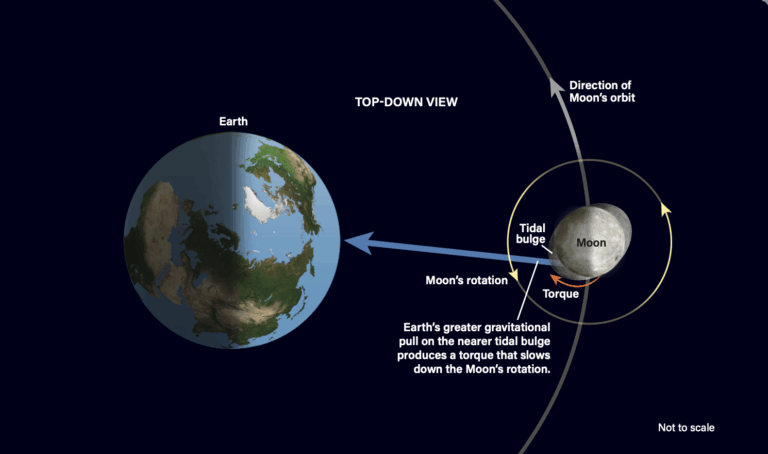

On the other hand, recent research has added new perspectives on some important issues about the calculations leading to the triumphant discovery. Soon after the discovery of Neptune, the American mathematician Benjamin Peirce suggested that Adams and Le Verrier had been lucky rather than good in some of their assumptions. In particular, those relating to the 2:1 orbital resonance between Uranus and Neptune. (For every orbit Neptune completes, Uranus completes roughly two.) Such resonances can wreak gravitational havoc: At the resonance itself, the planets’ orbits become unstable.

Adams and Le Verrier assumed Neptune was just outside the resonance, allowing its orbit to remain stable. But there were early hints that this was an incorrect assumption. As Adams refined his sixth and final set of calculations, he grew nervous: The planet’s predicted orbit was getting uncomfortably close to the 2:1 resonance, which would make it unlikely to exist at all. But his worries had been misplaced. In fact, it was quickly determined after its discovery that Neptune lies just inside the 2:1 resonance. As a result, Peirce argued that the apparent accuracy of Le Verrier and Adams’ calculations was a “happy accident.”

Most astronomers at the time, including Adams and Le Verrier, dismissed Peirce’s criticism — after all, the predictions had been accurate enough to successfully find Neptune. But Peirce had a valid point. The 2:1 resonance between the ice giants turns out to be extremely important in understanding how the planets’ gravitational pulls affect each other’s orbits.

This was clearly shown in 1990, when a team of researchers at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) published a paradigm-shifting paper that cleverly simplified the main features of the perturbation problem, eliminating the need to grasp the intricate arcana of classical celestial mechanics. With their model, they showed that the 2:1 resonance of Neptune perturbs Uranus’ orbital motion by an order of magnitude more than what Le Verrier and Adams had assumed. Le Verrier and Adams never uncovered these effects because they used incorrect values for Uranus’ orbit, including its eccentricity and average distance from the Sun.

The reason the orbital perturbations were much stronger than Le Verrier and Adams thought is related to the fact that the 2:1 resonance is not exact. (The period of Neptune differs from twice that of Uranus by 2 percent.) Though Le Verrier and Adams worried about the 2:1 resonance destabilizing their calculations, they couldn’t anticipate a side-effect of the actual near-resonance. Namely, the orbital perturbation Uranus experiences undergoes “beats,” slow variations in amplitude that occur when two objects are very nearly, but not quite, in resonance, like strings of a musical instrument slightly out of tune.

In light of this analysis, it turns out Le Verrier and Adams’ incomplete understanding of perturbation theory led them to make two mistakes. First, they made the deviations symmetric around the 1822 Uranus-Neptune conjunction, which was incorrect. The deviation from the mean motion that they thought was a maximum during this period was actually a minimum. Second, they entirely missed another possible location for Neptune, 180 degrees out of phase from the first, on the opposite side of the Sun! That they chose the position they did, which happened to be near the planet at the time, was indeed a happy accident.

Nevertheless, their efforts represented a significant accomplishment. According to CUHK physicist Kenneth Young, who co-authored the 1990 paper, “Le Verrier’s and Adams’ calculations were valid within the limitations of the theory they used.” In fact, Young adds, “even a search with many fewer parameters than those actually involved would have been a major computational endeavor in the days before electronic computers.”

So, the fulfillment of their prediction in d’Arrest’s exclamation, “That star is not on the map!” proves not to have been, as expected by later investigators, a model for future planetary discovery. Instead, it was a freak event, not likely to be repeated again in the history of astronomy.