Key Takeaways:

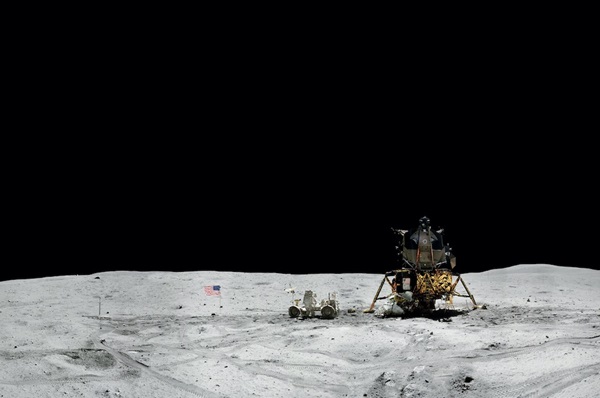

By the spring of 1972, traveling to the Moon was, if not routine, at least a more confident affair. When Apollo 16 astronauts John Young and Charlie Duke stepped off the ladder of the Lunar Module (LM) Orion onto the lunar surface, “there wasn’t any tentative step,” Duke later said. “It was just: Jump off and start work.”

When Duke and Young hit the regolith, it marked the first time that astronauts had set foot in the rugged lunar highlands. Apollo 16’s landing site was Descartes, a region some 7,400 feet (2,250 meters) higher than the Sea of Tranquillity, where Apollo 11 had touched down. Researchers believed the Descartes hills had been formed by lava flows and would yield volcanic material — like igneous rocks — older than the maria where Apollos 11 and 12 had landed.

For the laconic Young, the mission’s commander, it was the second trip to the Moon, having orbited it as the Command Module Pilot (CMP) on Apollo 10. He was also a veteran of the Gemini program, having flown on Gemini 3 and commanded Gemini 10. Duke, the mission’s Lunar Module Pilot, was an enthusiastic rookie; Apollo 16 would be his first and only spaceflight. Ken Mattingly had been slated to fly as CMP on Apollo 13 but was grounded after being exposed to the measles and shifted to Apollo 16.

All the while, uncertainty hung over the future of NASA. Political support for crewed space exploration had cooled. U.S. Vice President Spiro Agnew, speaking to launch controllers at Kennedy Space Center shortly after launch, joked, “I think you are getting a little bit bored with this thing, aren’t you?” But even with the end of Apollo in sight, the crew of 16 delivered, carrying out an expedition that brought its fair share of snafus and scientific surprises.

* * *

Apollo 16 got off to an inauspicious start, with a string of minor glitches. Paint was flaking off the LM’s insulation for no apparent reason. The crew discovered a software bug that crashed the guidance system. Upon arriving at the Moon, the LM’s communications antenna jammed and its landing radar malfunctioned. Charlie Duke had issues zipping up his spacesuit. And when he finally did, his mic was positioned awkwardly: It tended to bump into his drink tube, spraying the inside of his helmet with an orange-flavored sports drink. (The liquid was laced with potassium to ward off irregular heartbeats that had affected some previous Apollo astronauts.) So, when Young and Duke finally climbed into Orion and separated from the Command Module (CM) Casper, spirits were high. It seemed the mission was back on track.

Young (to CM): Boy, Ken, you look great!

Mattingly (to LM): Well —

Duke (to CM): You really got a pretty spacecraft!

Mattingly (to LM): Yours is a [garbled] pretty one, too.

Jim Irwin, Capsule Communicator (CapCom): Orion, this is Houston. How do you read?

Duke: Roger. You’re five by [five], Jim, and we’re sailing free. [Pause.] OK, Jim. It was a little rushed, but we got it done. The only bad thing is, I got a hat full of orange juice.

The two craft were in an elliptical orbit that dipped to just 11 miles (18 kilometers) above the lunar surface near the landing site. While on the farside of the Moon and out of contact with Houston, Mattingly in the CM would raise Casper’s orbit using the Service Module’s main engine. It was less than an hour before Young and Duke would begin their descent.

Duke (onboard LM): Here we go.

Young (onboard LM): Now, shall we do it?

Duke (onboard LM): Oh …

Young (onboard LM): Might as well. […]

Young: Ken, do you read us on VHF [Very High Frequency radio]? Over.

Mattingly: Yes, loud and clear.

Young: You fixing to do the burn, right?

Mattingly: Sure am.

It was then that Apollo 16’s most serious problem hit: Before the circularization burn, Mattingly had to run an automated test of all four of the Service Module’s engine gimbals, two in the primary system and two in the backup system. These gimbals swiveled the engine to steer its direction of thrust. Mattingly recalled the test in a 2001 NASA oral history: “So you start the little computer program, and it just automatically swings the gimbal up, swings it down, left, right, puts it back in the center, switches over to the other [backup] system, and does the same thing, and you just watch it. It’s a little thing that you do, kind of a ritual, happens about 20 seconds before the burn.”

While Young and Duke waited for Mattingly to light Casper’s engine, the pair tried to wipe down Duke’s helmet.

Young (onboard LM): Ain’t the clearest in the world, but it’s the clearest I could do, Charlie. Honest.

Duke (onboard LM): It’s terrible.

Young (onboard LM): You want to try it yourself? Just doesn’t come off. […] OK, we’re getting — we’re getting behind the timeline probably — maybe.

Duke (onboard LM): No, we aren’t. We’re OK.

Young (onboard LM): OK, nothing we can do here, huh?

Onboard Casper, Mattingly realized he had a problem. In the gimbal test, the second set of yaw gimbals was oscillating violently, causing the entire spacecraft to shake. Not knowing what the issue was, he started to blame himself. In 2001, he recalled: “[I’ve] practiced this stuff so much, it’s like knowing your name. […] We had already done this a couple of times on our way out, so it’s not like the first time we’d done this test, only this time the spacecraft was [shaking]. I stopped. [I thought,] ‘Oh, God. I’ve done this a thousand times. How could I screw it up now? I’ve got to do this again.’ ”

Mattingly (to himself): [garbled] marked. [garbled] [Long pause.]

[garbled] yaw. [garbled] [Pause.]

[garbled] [Pause.] It’s not gonna work.

Young (onboard LM): [sarcastically] Charlie, this is fun, by golly. [Laughs.] It’s really — it’s really — it’s the worst sim I’ve ever been in.

Mattingly (to himself): I be a sorry bird.

Mattingly: Hey, Orion?

Young: Go ahead, Ken.

Mattingly: I have an unstable yaw gimbal, no. 2. It’s just been oscillating and — oscillates in yaw any time it gets excited.

Young: Oh, boy.

Mattingly: You got any quick ideas?

Young: No, I sure don’t.

Unless the problem was resolved, mission rules dictated the landing could not continue.

While Mattingly tried to troubleshoot the gimbal problem with Houston, Young and Duke braced themselves for Houston to cancel their landing. “Our hearts sank,” Duke said in a 1999 NASA oral history. “If your heart can sink to the bottom of your boots in zero gravity, ours did, because there we were, two years of training, 240,000 miles [386,000 km] away, an hour before the landing, on an orbit you can look down at your landing site, 8 miles [13 km] beneath you, and they’re about to tell you to come home.”

Young (onboard LM): Man, I’m ready. I’m ready to go down and land. I think that’d really be neat.

Duke (onboard LM): I bet we dock and come home in about three hours.

The crew spent one more trip around the Moon waiting in agony. When they came around the lunar farside on their 15th lunar orbit and reestablished radio contact with Houston, they got good news: The landing was back on.

Irwin: We’ve run exhaustive tests down here, on the West Coast and East Coast on controllability aspects and structural aspects, and everything looks satisfactory. On Apollo 9, we ran — a similar test was run, as you probably remember. […] So we’re convinced down here that we have a satisfactory control mode if we have to revert to that one. Over.

In Mission Control, Stuart Roosa, the Command Module Pilot for Apollo 14, took over the CapCom’s mic to add more words of reassurance.

Roosa: You know, Jim was talking about the Apollo 9 test, and he said that you really feel it in the spacecraft. But this thing is stable. They’ve really checked that out, and it’ll rattle and roll a little bit if you have to use it, but it’s stable.

Mattingly: Sounds good. Once again, the ground earns their pay.

From there, the landing was smooth sailing. The site was on the Cayley Plains, nestled between two peaks of the Descartes Highlands — Smoky Mountain to the north and Stone Mountain to the south. Each mountain sported a nearby crater with prominent rays — North Ray and South Ray craters. Geologists hoped these craters would serve as natural drill holes where the crew could find samples of the underlying bedrock. Young and Duke set Orion down roughly 906 feet (276 m) from their target, near two craters named Double Spot.

Duke: Contact. Stop. Boom! PRO. ENGINE ARM. Wow! [garbled] man! Look at that! […]

Young: Well, we don’t have to walk far to pick up rocks, Houston. We’re among them. […]

Duke: Old Orion is finally here, Houston. Fantastic!

Irwin: Sounds great.

* * *

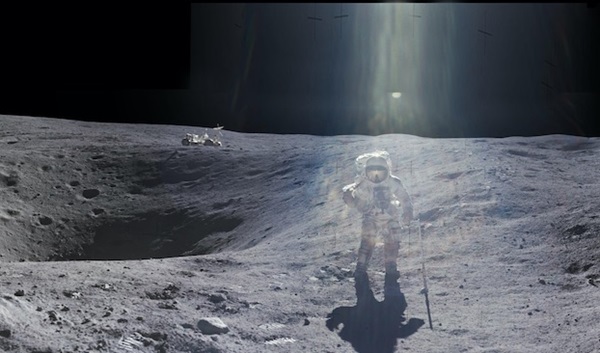

With the long delay, the crew opted to sleep and push back their first scheduled extravehicular activity (EVA) to the next day. The next morning, as Young clambered down the ladder, Duke couldn’t wait to get onto the lunar surface.

Duke: Hey John, hurry up!

Young: I’m hurrying. OK.

With that, Young stepped onto the Moon.

Young: There you are, our mysterious and unknown Descartes. Highland plains. Apollo 16 is going to change your image.

Duke was next to bound down the ladder.

Duke: Here I come, babe! […] Hot dog, is this great! […] Fantastic. That’s the first foot on the lunar surface. It’s super, Tony.

Anthony (“Tony”) England (CapCom): Sounds great.

Before they began their excursion, the pair set up the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), a suite of stationary scientific instruments. One highlight was an experiment developed by Columbia University’s Marcus (“Mark”) Langseth to measure the heat flow within the Moon’s interior. It was an upgraded version of a kit that had flown on Apollo 15; on that mission, problems with the drill prevented the heat probes from being planted at their intended depth.

Duke: OK. Man, you can’t believe how happy I am that [the first drill stem] went in there.

Young: Tony, he’s very happy.

England: Mark’s pretty happy, too.

But as Young worked at the ALSEP’s central station, with wires tangled at his feet, he accidentally caught his foot on a cable and stumbled.

Young: Charlie …

Duke: What?

Young: Something happened here.

Duke: What happened?

Young: I don’t know. Here’s a line that pulled loose.

Duke: Uh-oh.

Young: What is that? What line is that?

Duke: That’s the heat flow. You’ve pulled it off.

Young: I don’t know how it happened. Pulled loose from there?

Duke: Yes.

Young: God almighty. Well, I’m wasting my time. I’m sorry. I didn’t even know — I didn’t even know it. [Pause.] It’s sure gone —

England: Did the wire or the connector come off?

Young: — our first catastrophe. It broke right at the connector.

Duke: The wire came off at the connector.

England: OK, we copy. OK, I guess we can forget the rest of that heat flow.

Duke: Now, if I go do the — ah, rats!

Young: I’m sorry, Charlie. You know it.

Young took the mishap hard — he knew how hard Langseth and the other mission scientists had worked on the experiment. But there was nothing to do except carry on.

After deploying the rest of the ALSEP, the pair set out in the rover on their first traverse: a short excursion about 0.9 miles (1.5 km) west to Flag Crater, a crater nearly 800 feet (240 m) wide. There, they hoped to collect samples representative of the Cayley Formation. One rock caught the eyes of the scientists in the backroom in Mission Control, led by geologist William Muehlberger.

England: As you come around there, there is a rock in the near field on this rim that has some white on the top of it. We’d like you to pick it up as a grab sample.

Duke: This one right here?

England: That’s it. […]

Duke: OK, that’s a —

Young: That’s a football-size rock.

Duke: It’s a “Great Scott” size.

On Apollo 15, Commander David Scott had collected the largest Moon rock to date.

Young: Are you sure you want a rock that big, Houston?

England: Yeah, let’s go ahead and get it.

Young: That’s 20 pounds [9 kilograms] of rock right there.

Duke: OK. It has some big clasts in it, John.

Young: It sure has.

Duke: If I fall into Plum Crater getting this rock, Muehlberger has had it.

England: We agree.

Duke: OK, I’ve got it. […] Oh, Tony, it’s got some beautiful crystals in it though. That was a good guess.

England: Good show.

Hartsfield: I guess the big thing, Ken, was they found all breccia. They found only one rock that possibly might be igneous.

Mattingly: Is that right? [Laughs.]

Hartsfield: Yeah. I guess the guys are a little bit surprised by that.

Mattingly: […] [Laughs.] Well, it’s back to the drawing boards, or wherever geologists go.

Inside the LM, as Young and Duke prepared to sleep, Duke paid tribute to the mission geologists who had trained them.

Duke: Let me say that all our geology training, I think, has really paid off. Our sampling is really — at least, procedurally — has been real team work, and we appreciate everybody’s hard work on our sampling training.

England: OK. And I sure think it’s paying off. You guys do an outstanding job.

Young: Yeah. You noticed how good I carried the bags, huh?

Unbeknownst to Young, his radio remained open, allowing Houston — and the press corps — to eavesdrop on a decidedly private conversation.

Young: I got the farts again. I got ’em again, Charlie. I don’t know what the hell gives it to me. Certainly not — I think it’s the acid in the stomach. I really do.

Duke: It probably is.

Young: I mean, I haven’t eaten this much citrus fruit in 20 years! And I’ll tell you one thing, in another 12 f—— days, I ain’t never eating any more! And if they offer to sup[plement] me potassium with my breakfast, I’m going to throw up! [Pause.] I like an occasional orange — really do. [Laughs.] But I’ll be darned if I’m going to be buried in oranges.

After a few more minutes of unguarded conversation, Houston intervened.

Joe Allen (CapCom): Orion, Houston.

Young: Yes, sir.

England: OK, uh, John. You — we have a hot mic.

Young: How… How long have we had that?

England: OK. It’s been on through the debriefing.

Young: How could we be on hot mic with normal voice? […]

England: John, would you exercise your push-to-talk button there? It may be stuck.

Young: Yeah, I hit it then.

England: John, it doesn’t seem to be a hot mic now. Evidently, you got it off.

Young: OK. Fine.

* * *

The next day, Young and Duke trekked to the lower slopes of Stone Mountain, 2.4 miles (3.8 km) south. Driving the rover up a 20 percent grade, they reached a cluster of five craters, called the Cincos, 500 feet (150 m) above the Cayley Plains. Their goal was to find chunks of the mountain’s bedrock — true samples of the Descartes Highlands. However, this was complicated by the nearby presence of South Ray Crater on the plains below: The crew realized that many of the craters they were seeing were secondary craters formed by flying debris from the South Ray impact.

Duke: You know, John, with all this — these rocks here, I’m not sure we’re getting [samples of] Descartes.

Young: That’s right. I’m not either.

Duke: We ought to go down to a crater without any rocks. […]

As Young and Duke stood at the rim of one secondary crater with a rake for collecting samples, they debated the best spot to sample from.

Duke: This is steep. OK, where do you want this [rake]?

Young: Well, on the rim, I think, Charlie.

Duke: Why don’t we get outside the rim? That would be definitely Descartes, right down here. OK?

Young: The object is to get the stuff that’s been knocked out of the ground [bedrock from the deepest point] and landed on the rim.

Duke: Yeah, I know it, but I thought that would definitely — we could say that would be definitely — oh, OK, I’ll sample right up here.

The next day’s third and final EVA was originally going to be cancelled due to the landing delay, but it was retained at the insistence of the science team. They argued that EVA 3’s main target, North Ray Crater, offered the mission’s last, best chance to find Descartes bedrock material.

Indeed, North Ray Crater was a crown jewel of the area. At roughly 3,600 feet (1.1 km) in diameter, it was nearly as large as Arizona’s Meteor Crater — and with even steeper slopes, as the pair found out.

Young: Man, does this thing have steep walls.

Duke: They said 60 degrees.

Young: Well, I tell you, I can’t see to the bottom of it and I’m as close to the edge as I’m gonna get. That’s the truth. […]

England: Man, is that a hole in the ground!

Duke: […] It really is. I see no bedrock, though. All I see is boulders around the crater. There’s nothing that reminds me of bedding, just loose boulders.

Though no bedrock seemed available to sample, the crew took the opportunity to scout and sample an enormous boulder several hundred feet in the distance.

Duke: Look at the size of that biggie!

Young: It is a biggie, isn’t it. It may be further away than we think because —

Duke: No, it’s not very far. It was just right beyond you.

Young: Theoretically, huh?

Apollo crews found it notoriously difficult to judge distances on the Moon. The lack of air meant distant terrain never appeared hazy as it would on Earth, robbing astronauts of a helpful distance cue.

Duke: Look at the size of that rock!

England: We can see.

Duke: The closer I get to it, the bigger it gets.

The next day’s third and final EVA was originally going to be cancelled due to the landing delay, but it was retained at the insistence of the science team. They argued that EVA 3’s main target, North Ray Crater, offered the mission’s last, best chance to find Descartes bedrock material.

Indeed, North Ray Crater was a crown jewel of the area. At roughly 3,600 feet (1.1 km) in diameter, it was nearly as large as Arizona’s Meteor Crater — and with even steeper slopes, as the pair found out.

Young: Man, does this thing have steep walls.

Duke: They said 60 degrees.

Young: Well, I tell you, I can’t see to the bottom of it and I’m as close to the edge as I’m gonna get. That’s the truth. […]

England: Man, is that a hole in the ground!

Duke: […] It really is. I see no bedrock, though. All I see is boulders around the crater. There’s nothing that reminds me of bedding, just loose boulders.

Though no bedrock seemed available to sample, the crew took the opportunity to scout and sample an enormous boulder several hundred feet in the distance.

Duke: Look at the size of that biggie!

Young: It is a biggie, isn’t it. It may be further away than we think because —

Duke: No, it’s not very far. It was just right beyond you.

Young: Theoretically, huh?

Apollo crews found it notoriously difficult to judge distances on the Moon. The lack of air meant distant terrain never appeared hazy as it would on Earth, robbing astronauts of a helpful distance cue.

Duke: Look at the size of that rock!

England: We can see.

Duke: The closer I get to it, the bigger it gets.

Appropriately dubbed House Rock for its size, the boulder was one of the most impressive seen on any Apollo mission. Excavated by the North Ray impact, its samples gave scientists one of their best looks at lunar highlands material.

When Young and Duke returned to the LM, they had planned to stage a lighthearted “Lunar Olympics” for the TV camera. After all, 1972 was an Olympic year. But time was running short.

Young: We were gonna do a bunch of exercises that we had made up as the Lunar Olympics to show you what a guy could do on the Moon with a backpack on, but they threw that out.

As Young talked, he decided to show off his high-jump abilities, repeatedly jumping up and down in front of the rover’s camera.

England: For a 380-pound [172 kg] guy [including the weight of the spacesuit], that’s pretty good.

The camera panned over to Duke, who also started jumping up and down.

Duke: Yeah, jump flat-footed straight in the air, three hundred — about 4 feet [1.2 m]. Wow!

Then, Duke had a brush with disaster. Losing his balance, he toppled over backward, his legs flailing — and his critical life support systems in his backpack about to impact the surface. “That was a moment of panic,” he said in 1999. “I really — you know, I was in trouble. You could watch me scrambling like that, trying to get my balance. And my heart was just pounding. You know, the backpack is very fragile. I thought the suit would hold, but the backpack, with the plumbing and connections and all — if that broke, it was just like having a puncture in the suit.”

Young: [disapprovingly] Charlie!

Duke: That ain’t any fun, is it?

Young: That ain’t very smart.

Duke: That ain’t very smart. Well, I’m sorry about that.

Young: Right. Now we do have some work to do.

After returning to the LM and securing their samples, Young and Duke immediately prepared to depart the Moon.

After a successful rendezvous with Casper, the crew could reflect on what had been, despite all the gremlins, a successful field expedition. Over the course of 20 hours and 14 minutes of EVA, the rover covered 16.6 miles (26.7 km) and Young and Duke collected roughly 209 pounds (95 kg) of samples. The lack of igneous rocks suggested that Apollo 16’s landing site had been shaped less by volcanoes and more by impacts and the resulting massive rock flows. It taught geologists an important lesson — that lunar terrain was more complex than it might appear from orbit.

The next day, the crew lit the Service Module engine once more to begin their journey back to Earth.

On the mission’s 11th day, less than 24 hours before Apollo 16 splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, the crew took part in a press conference, answering questions from reporters relayed to them by CapCom Henry Hartsfield. Though the press had many questions for the astronauts about the expedition’s numerous technical glitches, the lead topic of that day’s news cycle was clear.

Hartsfield: Apollo 16, the questions in this press conference have been prepared by newsmen covering the flight here at the Manned Spacecraft Center. I’m going to read them to you exactly as worded by the newsmen and in a priority specified by them. Question no. 1 for John Young: “A couple of times you were on hot mic and didn’t know it, but how could a nice Florida boy like you say what you did about citrus fruit?”

Crew (onboard): [Laughter.]

Young: That’s a very good question. Wait until you drink it day and night for two weeks and let me know what you think.