Compared to the universe, human perspective is tiny. The fastest thing we know of is light, which travels at 186,282 miles (299,792 kilometers) per second. It takes light 8.3 minutes to travel from the Sun to Earth. Light needs over four years to cross the distance to the closest star outside our solar system, and 26,000 years to reach the center of the Milky Way. The nearest galaxy like our own is a dizzying 2.5 million light-years distant — but the rest of the universe? The rest of the universe is mind-bogglingly far away.

The latest estimates suggest there are over 200 billion galaxies in the universe, and over 90 percent of them are more than a billion light-years away. In fact, the light we see today from more than two-thirds of those galaxies was emitted before Earth even formed. We occupy a tiny, minuscule portion of a vast, vast cosmos.

It is difficult for the human mind to contemplate such tremendous scales, and just as difficult to study the myriad of fascinating objects that lie at them. But human curiosity and ingenuity is rising to that challenge. Our arsenal of astronomical tools has grown and improved at an ever-increasing rate over the past couple of hundred years. And so has another key factor in understanding the universe: the artists who depict those tremendous scales and fascinating objects.

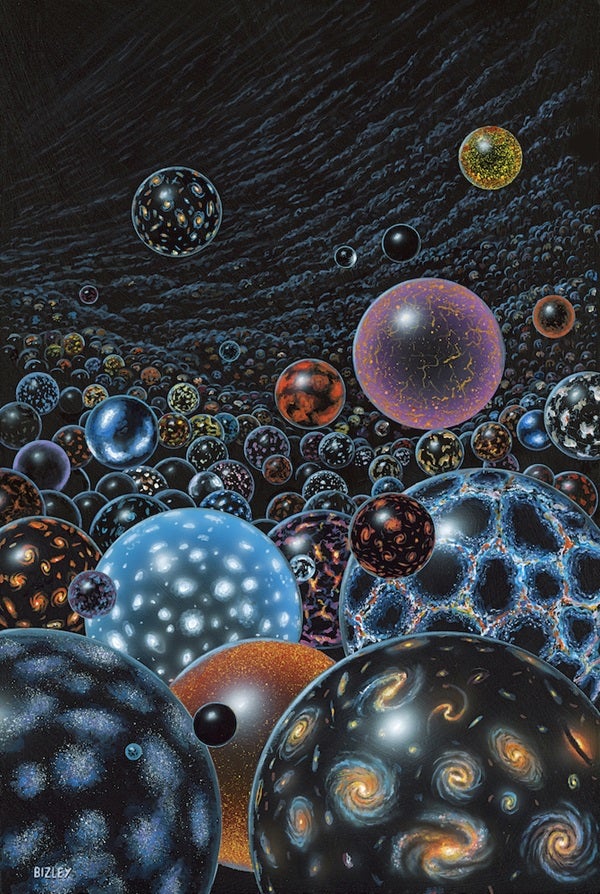

Humans are visual creatures. For us, being able to see something is crucial to understanding it. Unfortunately, the farther away an object lies, the harder it is for our astronomical tools to see. But the imagination of an artist can leap across those light-years to paint a picture from a closer or different perspective, and bring new understanding. Artists have done this since the beginning of astronomy, and nowhere has this been more useful than in studying objects in the ever-increasing depths of space outside our own galaxy.

In the 1960s, Fritz Zwicky compiled a catalog of galaxies and galaxy clusters with nearly 40,000 objects in it. This catalog wasn’t heralded just by scientists; it inspired artists by giving them a veritable smorgasbord of galactic shapes to paint. Spirals, barred spirals, ellipticals, lenticulars, irregulars, ringed galaxies, interacting galaxies — the artistic possibilities were breathtaking, and so were the images artists created in response.

We now have photographs of millions of galaxies from optical telescopes both on and off Earth. All of them have the same, limited viewpoint: looking in from afar. But an artist can show us what a sky filled with a cluster of galaxies would look like from deep space, or the view of a galaxy from the surface of a nearby planet. Artists can drop us into the center of a distant gaseous whirlpool, or spread a spiral arm of stars across the sky to marvel at — sights our earthbound cameras will never be able to capture.

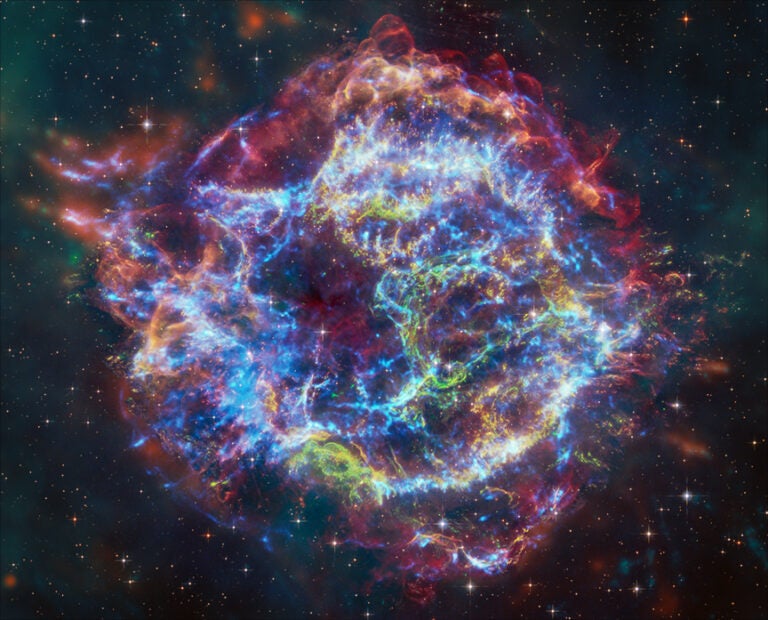

There is more to the universe than just visible light, though. Radio telescopes like the Very Large Array in New Mexico and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile have opened new realms of discovery, as have instruments that can collect X-rays, gamma rays, neutrinos, and even gravitational waves. Each new type of telescope has opened new ways to study the universe — like sampling particles from the cores of exploding stars and sensing the ripples in space-time caused by colliding black holes. With all of these come new artistic opportunities.

As fascinating as these rich troves of new data are, we cannot see what a radio telescope or gravitational-wave observatory sees. The data are just numbers. Although we can sometimes create false-color images from the streams of ones and zeros, their resolution is limited. But a skilled astronomical artist can take the reams of non-visible observations from an active galaxy 100 million light-years away and create a plausible up-close image depicting an erupting galactic core with vast jets of material shooting into the void, vividly illustrating the physics of these immensely powerful objects. Depictions of rarer and more mysterious deep-space objects rely even more heavily on artistic skill — like the event horizons of supermassive black holes, protogalaxies, and fast radio bursts.

Artists can also make sense of the most tenuously connected structures in the cosmos. For most of the 20th century, astronomers assumed that galaxy clusters were the universe’s largest organized collections of matter. But in the 1980s, astronomers realized that structure exists on a much larger scale. Surveys detected vast walls and humongous filaments of galaxies crisscrossing the universe, and great empty voids that span hundreds of millions of light-years.

More recently, astronomers have analyzed hundreds of thousands of galaxies cataloged in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and found that filaments may also have coherent motion. In 2021, a team of astronomers reported that these structures appear to rotate, their galaxies twisting around each other in astonishingly gigantic displays of angular momentum. The scale of such structures is almost unimaginable, but a well-crafted image can convey their immensity and complexity in an instant.

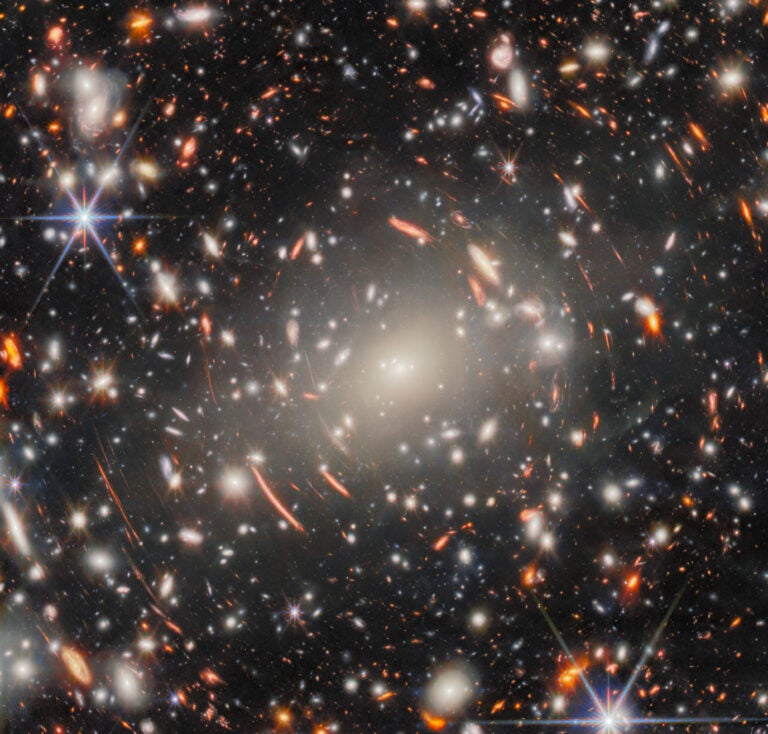

Hubble Ultra Deep Field, Digital photograph

The Hubble Ultra Deep Field (2014) was produced by combining over 2,000 exposures of the same small spot of sky taken over 10 years into one image. This image is made up of roughly 25 days of exposure time and shows about 10,000 galaxies.

Red Galaxy Sunset, Digital

A barred spiral galaxy dominates the sky as it sets over the ocean of a distant planet populated with alien life forms.

View of a Pulsar From a Lonely Planet, Digital

A lifeless world is bathed in intense radiation from a quasar, even from tens of thousands of light-years away.

Extra-Galactic Web, Digital

Extragalactic space is much more tenuous than interstellar space or the interior of the solar system, but even the emptiest places are not completely empty. Gas surrounds galaxies and exists between them in a great weblike structure called the cosmic web.

Galactic Islands, Digital

The spiral arms of a galaxy are splayed in the foreground, bursting with hot, young stars giving off blue light. The radiation from these stars are energizing patches of hydrogen gas, which glow red.

Cradle of Life, Digital

The Next Generation Very Large Array (ngVLA) is the proposed successor to the Very Large Array. It would be the flagship facility of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, which commissioned this artwork. The piece symbolically portrays ngVLA and the objects it will study.