Key Takeaways:

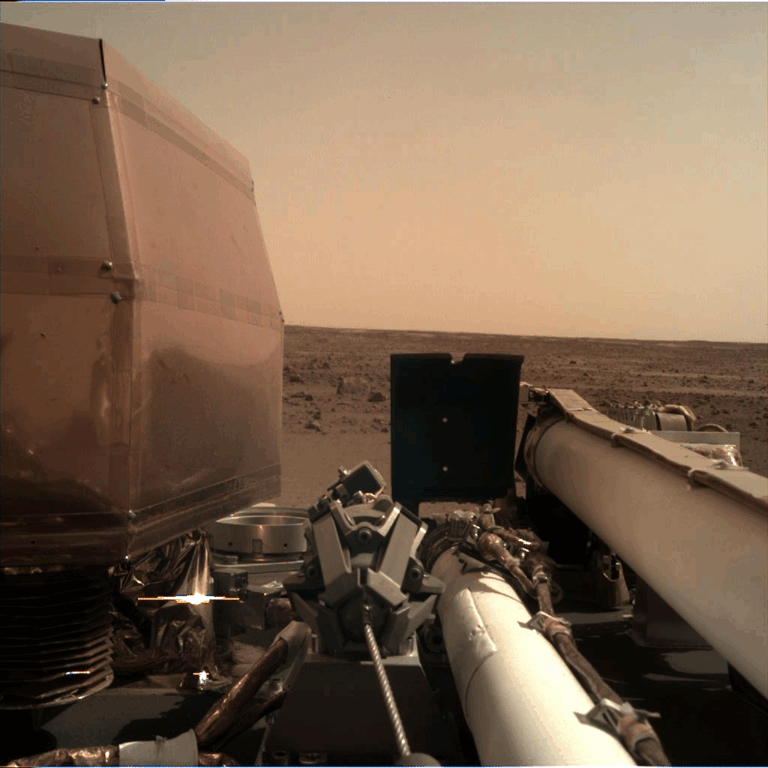

Mars is a world entirely populated by robots: Orbiters and landers from a half-dozen space agencies scout its wafer-thin atmosphere and stark surface to unveil a surprisingly active past. On the ground, a hardy six-wheeled rover named Curiosity observed its 10th anniversary on the Red Planet this summer. Dust-streaked and running on punctured wheels, it continues to explore a desiccated landscape of wind-chiseled mesas, isolated buttes, and swirling sands for relics of a warmer, wetter, perhaps habitable Mars.

The idea of life on the Red Planet has long exerted an irresistible pull, from the canals imagined by Percival Lowell to the monstrous otherworldly tripods of H.G. Wells to the classic lyrics of David Bowie. But while life-forms would find it difficult to thrive on this radiation-drenched wasteland, the infant Mars 3.5 billion years ago was unlike today’s grizzled, middle-aged world. Girdled by a thick carbon dioxide atmosphere and with free-flowing water on its surface, conditions then may have permitted life to take root.

Today, our quest to find hints of that life continues — not with observations from earthbound telescopes, but with on-the-ground reconnaissance from an ever-growing lineage of robotic explorers.

A rover is born

The car-sized Curiosity’s story truly began in 2003, when the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) — a mission to deliver a new rover to the Red Planet — earned hearty endorsement from the National Research Council. NASA chose 11 scientific instruments from seven nations, aiming to launch MSL in October 2009.

But costs spiraled. The initial $1.63-billion price tag swelled to more than $2 billion. To save money, spare parts were deleted, tests modified, and software redesigned. Engineers removed a zoom function on the rover’s Mastcam camera and replaced a rock-grinding device with a motorized wire-bristle brush.

It was not enough. Testing and hardware complexities made a 2009 launch unattainable. MSL was delayed to the next Mars launch window in late 2011.

The same complexities that slowed the launch and gave NASA headaches in 2009 are today part of Curiosity’s success. The rover’s 7-foot-tall (2.1 meters), multi-jointed robot arm is strong, yet sufficiently agile enough to drop an aspirin into a thimble. A cross-shaped turret houses five instruments, among them a percussive drill (the Rock Abrasion Tool or RAT), the motorized brush (called the Dust Removal Tool or DRT), and a scoop called the Collection and Handling for In-situ Martian Rock Analysis (CHIMRA) to gather, sieve, and portion soil specimens.

Also atop the turret, the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS) irradiates samples and maps X-ray emissions to measure chemical constituents. And the Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI), with a focus range from 0.8 inch (2 centimeters) to infinity, snaps high-resolution pictures. It has acquired multiple self-portraits of the rover on Mars, winning awards for the best “space selfies.”

The Rover Environment Monitoring Station (REMS) on the mast measures local humidity, temperature, pressure, and wind. One of its two anemometers was hit by a rock during landing, but the other works just fine. REMS also analyzes ultraviolet radiation at the surface to better inform future human missions.

The Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) collects, heats, and analyzes soil and atmospheric specimens. The Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN) looks for subsurface water at depths up to 2 feet (0.6 m). The Chemical and Mineralogy (CheMin) instrument uses X-ray diffraction to measure mineral abundances. And the Chemistry and Camera complex (ChemCam) employs infrared laser pulses to zap rocks from up to 23 feet (7 m) away and observe their emitted spectra.

Name and address

Engineers placed the names of 1.2 million people (including the author’s) onto the rover, inscribed on two microchips as part of the Send Your Name to Mars campaign. But MSL needed its own name. In partnership with Walt Disney’s 2008 Pixar movie WALL-E, NASA asked U.S. students aged 5 to 18 to find one.

More than 9,000 names were submitted. The winner, selected in May 2009, was suggested by 12-year-old Clara Ma of Lenexa, Kansas, who won a trip to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, to sign her name on the rover. “Without curiosity,” Ma wrote in her essay, “we wouldn’t be who we are today.”

Picking a landing site came next. Scientists mulled over dozens of locations, all exhibiting traces of Mars’ watery past, potentially housing biomarkers that ancient organisms might once have left behind. Curiosity’s robustness made previously hard-to-reach places now reachable. The right site, NASA noted in September 2008, “will combine a deep love of adventure with due respect for safety.” Safe, in this case, meant “flat and fairly free of rocks,” while adventure “generally involves streambeds, rugged terrain, and rocks exposed in steep cliff walls.”

In July 2011, NASA chose Gale Crater.

Destination: Gale Crater

Ninety-six miles (154 km) wide and covering an area equal to Connecticut and Rhode Island combined, Gale Crater today is a dry, desolate locale south of the martian equator. Its current state has more in common with the Badlands of southern Utah than the Garden of Eden. Named for the Australian astronomer Walter Gale (1865-1945) — who, like Lowell, was a proponent of canals and oases on Mars — the crater formed from an asteroid strike between 3.8 billion and 3.5 billion years ago.

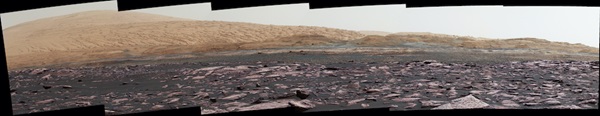

Over time, this gaping wound filled with sediment, first deposited by water, then by wind. Eons of erosion then scoured out the sediments to leave an isolated peak: the 18,000-foot-high (5,500 m) Aeolis Mons, nicknamed Mount Sharp for U.S. geologist Robert Sharp (1911-2004). Rising taller than Mount Rainier stands over Washington state and nearly three times higher than the Grand Canyon is deep, Mount Sharp’s layer-cake stratigraphy promised to lay bare some 3 billion years of the martian landscape’s evolution, and maybe even reveal how the planet morphed from an Earth-like paradise into an arid, rusty desert.

“Mount Sharp is the only place we can currently access on Mars where we can investigate this transition in one stratigraphic sequence,” said John Grotzinger of Caltech, then chief scientist for the mission, in a 2012 NASA press release. “The hope of this mission is to find evidence of a habitable environment; the promise is to get the story of an important environmental breakpoint in the deep history of the planet.”

Yet accessing Gale would be tough. Its potential to unlock a crucial chapter in Mars’ past had seen it considered for the earlier Spirit and Opportunity rovers; their limited capabilities and the challenging terrain ultimately ruled it out. But Curiosity, with a unique landing system and long-duration nuclear battery, would be a more capable beast.

Seven minutes of terror

Curiosity’s three-week launch window opened Nov. 25, 2011. That first day was missed, as engineers replaced a flight termination battery. But the Atlas V rocket speared into a cloud-dappled Florida sky at 10:02 A.M. EST on the 26th, “seeking clues to a planetary puzzle about life on Mars,” the launch commentator gushed. And thus, Curiosity began its 352-million-mile (567 million km) voyage to the Red Planet.

During the 36-week cruise, four mid-course correction maneuvers helped shift Curiosity’s landing point 4 miles (7 km) nearer to Mount Sharp. This correspondingly shaved months of drive time off the rover’s journey to reach selected sampling locations sooner.

Also during the cruise, the Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD) measured radiation levels inside a Marsbound spacecraft for the first time. Researchers hoped the readings would reveal the environment that humans might experience during a similar trip — and they did. Results published in 2013 highlighted the biggest solar particle event in a decade, finding that radiation levels surpassed NASA’s current astronaut career limit. One scientist opined that an astronaut’s accumulated radiation dose on the way to Mars would be like undergoing a full-body CT scan every week of the flight.

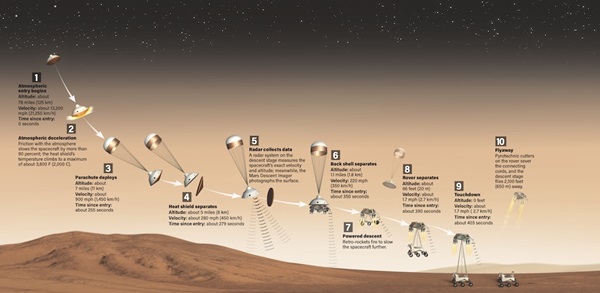

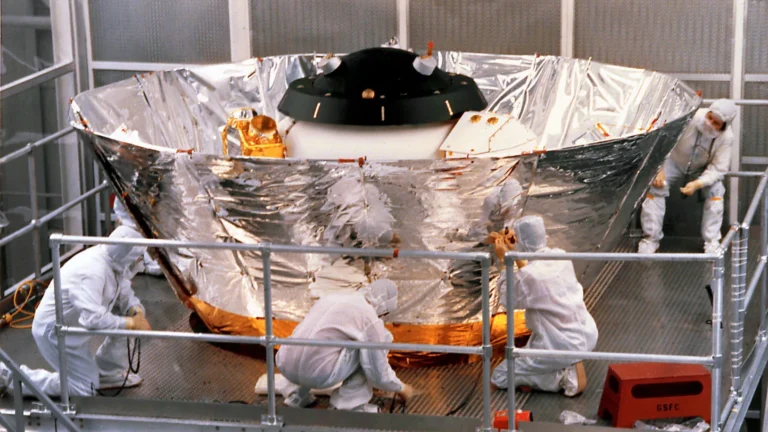

Curiosity reached the Red Planet after just over eight months of travel. Its approach for landing on Mars differed from earlier missions. At 1,982 pounds (899 kilograms), it was too heavy for just parachutes, landing legs, or airbags to carry it safely to the ground. Instead, Curiosity used an innovative new piece of technology: a rocket-powered sky crane that lowered the rover, wheels-down, to the surface on 25-foot (7.6 m) tethers.

Because of the immense distance between Earth and Mars, there is no way for earthbound controllers to land a rover in real time. Instead, an entirely autonomous procedure enabled Curiosity to land itself with pre-loaded software. NASA’s Mars Odyssey and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) watched from orbit, relaying their data back home. Seven minutes elapsed between when Curiosity reached the top of Mars’ atmosphere (called entry interface) and landed on the surface — and all the while, the rover’s status remained unknown. NASA called these the “seven minutes of terror.”

The craft discarded its cruise stage just before entry interface and the rover, still cocooned in its protective aeroshell, hit the thin atmosphere at 13,200 mph (21,250 km/h). The heat shield guarded its cargo from temperatures of 3,800 degrees Fahrenheit (2,000 degrees Celsius), as friction slowed its meteoric descent. Once Curiosity was plummeting at 900 mph (1,450 km/h), or 1.7 times the speed of sound, it jettisoned several tungsten ballast weights and its supersonic parachute opened, unfurling a canopy 165 feet (50 m) long and nearly 52 feet (16 m) wide.

Next, the craft discarded its aeroshell. The Mars Descent Imager (MARDI) on Curiosity’s chassis started recording video of the landing site. From orbit, MRO photographed Curiosity descending beneath its parachute. “You could consider us the closest thing to paparazzi on Mars,” joked MRO team member Sarah Milkovich when the photo was released. “We caught NASA’s newest celebrity in the act.”

At an altitude of 1.1 miles (1.8 km), the backshell containing the parachute detached. Still moving at 220 mph (350 km/h), the sky crane’s eight retrorocket engines, perched on extendible arms, roared to life, their exhaust almost invisible in the martian air. After it slowed to 1.7 mph (2.7 km/h), the rover’s wheels snapped into position as the crane began to lower Curiosity via tethers. At 1:32 A.M. EDT on Aug. 6, 2012, Curiosity plonked down onto alien soil. The sky crane paused a couple seconds for a “weight on wheels” signal, then cut the tethers and flew away to crash at a safe distance. (Curiosity serendipitously recorded the sky crane’s demise when one of its rear-mounted hazcams came online 40 seconds after landing and captured a plume of dust on the horizon.)

On Earth, flight controllers waited anxiously. First came the call of “Tango Delta nominal” — phonetically denoting “T D” for a safe touchdown — followed by verification that Curiosity was on firm ground, then confirmation of a strong ultra-high frequency (UHF) signal. Finally, the words “touchdown confirmed” visited a sheer pandemonium of cheering and joyous applause on the control room.

More than 3 million people watched online as Curiosity landed that morning. A thousand others gathered in New York’s Times Square for a live broadcast. JPL engineer Bobak Ferdowsi became an unexpected Twitter sensation with his yellow-starred Mohawk haircut. In the following days, Curiosity transmitted back to Earth words from NASA Administrator Charlie Bolden and played will.i.am’s “Reach for the Stars,” the first time recorded human voices had been broadcast to Earth from another planet.

Looking for signs of life

A laboratory like no other was ready to get to work.

The rover’s touchdown spot was named Bradbury Landing after science fiction writer Ray Bradbury, who had died earlier in 2012. Curiosity’s first port of call was Glenelg, a patch of terrain 1,300 feet (400 m) from the landing site. Along the way, ChemCam zapped its first target (the fist-sized Coronation Rock) with 30 laser pulses over 10 seconds, delivering more than a million watts of power per shot.

Analysis of a football-sized rock (named Jake Matijevic for MSL’s late surface operations chief engineer) drew parallels with volcanic materials on Earth, revealing high levels of feldspar and traces of magnesium and iron. Curiosity saw evidence of long-vanished streambeds with rounded gravel — ranging in size from grains of sand to golf balls — prompting excited suggestions that perhaps water had once flowed through the area at a comfortable human walking pace of 3 feet (90 cm) per second, rising to ankle or even waist height.

A wind-deposited ripple of sand called Rocknest gave Curiosity a chance to scoop up some soil. This revealed uncanny similarities with the weathered basalts of Hawaii. At a shallow depression called Yellowknife Bay, which might be the end of an ancient river system or intermittently wet lakebed, the rover first used its DRT to prepare a rock dubbed Ekwir-1 for inspection and mineralogical analysis.

In February 2013, Curiosity drilled into its first rock, nicknamed John Klein for the mission’s late deputy project manager. The 2.5-inch (6.4 cm) hole uncovered traces of sulfur, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and carbon, all key ingredients for life. Such findings — again showing Mars may have had flowing surface water just as the first signs of life appeared on Earth — kindled speculation that life on Earth and Mars might have arisen around the same time. Certainly, Yellowknife had pointed to habitable conditions for tens of millions of years, as lakes rhythmically emerged, dried, then re-emerged. Even when the soil was dry, the subsurface remained wet, as shown by mineral veins deposited into fractures in the rocks by underground water.

The planet’s past came even more alive at Cumberland, a patch of bedrock at least 3.9 billion years old, whose surface bumps were possibly forged by flowing water. SAM revealed organic molecules, though whether these could have formed on Mars or been transported by meteorites remains unclear. The rover also discovered smectite clays, which can absorb and retain water, potentially providing an environment for life to thrive.

Data from Hidden Valley on Mount Sharp’s lower flank, which Curiosity entered in 2014, suggested long-lived lakes existed there some 3.8 billion to 3.3 billion years ago. And in 2018, researchers announced that over the previous three years, Curiosity had observed ancient organic molecules within the Gale Crater region that contained carbon and hydrogen in sedimentary rocks within 2 inches (5 cm) of the surface.

Curiosity also found nitric oxides and organic salts, whetting many astrobiologists’ appetites. Nitrates can be processed by biological systems; their discovery thus provided another line of evidence in favor of Mars once having had suitable conditions for microbial life. None of these finds conclusively proved that life does or did once thrive in this now-blasted landscape; indeed, most compounds can arise through non-biological processes. But these underscored a growing realization that Mars’ past was far more hospitable than its present.

Up the mountain

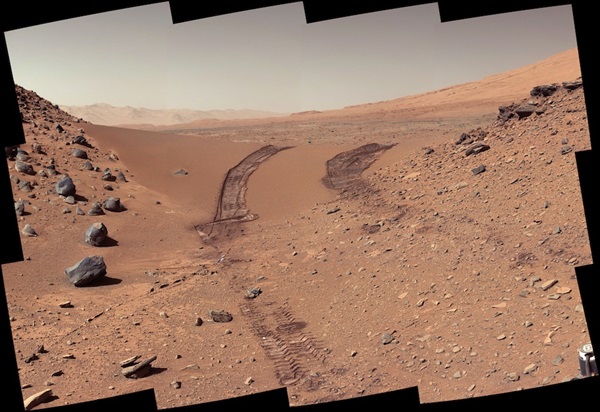

In July 2013, the rover began to head for the slopes of Mount Sharp to the southwest. To progress across difficult, rugged terrain, the engineers tested Curiosity’s autonomous navigation, with the Mastcam cameras identifying hazards in advance. This enabled Curiosity to compute its own route without requiring constant attention from its human handlers back home.

The journey from Bradbury Landing to the foothills of Mount Sharp took two years. Curiosity crested Panorama Point, photographed a pale-toned outcrop named Darwin, and observed the striated region called the Kimberley, including a 16-foot-high (5 m) isolated butte called Mount Remarkable. Rocks here were darker than the mudstone slabs of Yellowknife, revealing more magnetite and the presence of orthoclase, a potassium-rich feldspar. All this implied that Gale Crater underwent complex geological processing in the distant past, including multiple episodes of melting and possibly even volcanism.

Passing through a gap in a band of dunes and entering a rockier landscape, Curiosity’s exploration of Mount Sharp finally began in earnest in September 2014 at Pahrump Hills.

Since then, Curiosity has gingerly threaded its way up the slopes of Mount Sharp, surveying its lower levels and revealing the presence of an iron-oxide material called hematite. Later sampling halts revealed jarosite, which forms in acidic conditions, and the silica mineral cristobalite. Since these minerals are known to be formed or altered in wet environmental conditions, their discovery furnished important clues about multiple episodes of fluid motion in Mars’ far-off past. At higher levels, the rover found polygonal sand ripples, rockier terrain, and extraordinary sandstone plateaus carved by eons of wind erosion into isolated ridges and knoblike buttes.

But after a decade on Mars, Curiosity is clearly aging. By late 2014, the rover’s wheels were already showing signs of wear. Engineers began selecting routes to avoid sharp rocks and deployed driving techniques to alleviate pressure. By 2016, punctures had begun to perforate the wheels’ outer skins; the wheels are now monitored via imaging every 3,280 feet (1 km). Since 2017, software algorithms have been implemented to adjust the wheels’ speed while climbing to prevent slipping that can cause further damage.

Curiosity has also weathered multiple computer reboots, a transient short circuit in its arm, and trouble opening and closing CHIMRA’s scoop. Its percussion drill suffered a motor malfunction that suspended operations from December 2016 to May 2018. And in mid-2018, it survived the planet-circling dust storm that ended the life of the solar-powered Opportunity rover, leaving Curiosity as the only functioning rover on Mars for a time.

Ten years after arriving in Gale Crater, the rover has covered more than 17 miles (27 km), and Curiosity’s future remains to be seen. Little trace of the rover now survives at Bradbury Landing, as the martian wind and dust have long since begun to cover its earliest tracks. For now, though, Curiosity continues to live up to its name.

As Clara Ma wrote in her prize-winning essay, “Curiosity is an everlasting flame that burns in everyone’s mind.” And it surely guides the teams who tenderly watch over Curiosity as it greets each martian morning, prepared for whatever the day ahead may hold.

Curiosity for all

Public outreach goes hand in glove with science on what NASA has called a “mission for everyone.” MAHLI’s calibration target, which provides a reference for color and brightness in the rover’s images, includes a 1909 Lincoln penny — a tip of the hat to geologists’ practice of using coins to provide context. The choice has a public outreach function, too. “Everyone in the United States can recognize the penny and immediately know how big it is, and can compare that with the rover hardware and Mars materials in the same image,” said MAHLI principal investigator Ken Edgett in a press release. “The public can watch for changes in the penny over the long term on Mars. Will it change color? Will it corrode? Will it get pitted by windblown sand?