Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) is often recognized as the founder of modern physics, perhaps even the father of modern science itself. But this popular image neglects one important facet of his Renaissance personality: Galileo the artist.

Art and science have always been intertwined, and Galileo exemplified how they can inspire and inform one another. In addition to being a skilled observer and a keen thinker, he was a talented artist, trained in cutting-edge perspective techniques pioneered by his fellow Italian artists. His artistic sensibility played a key role in his scientific insights, leading some 400 years ago to a new picture of the universe.

A man of science

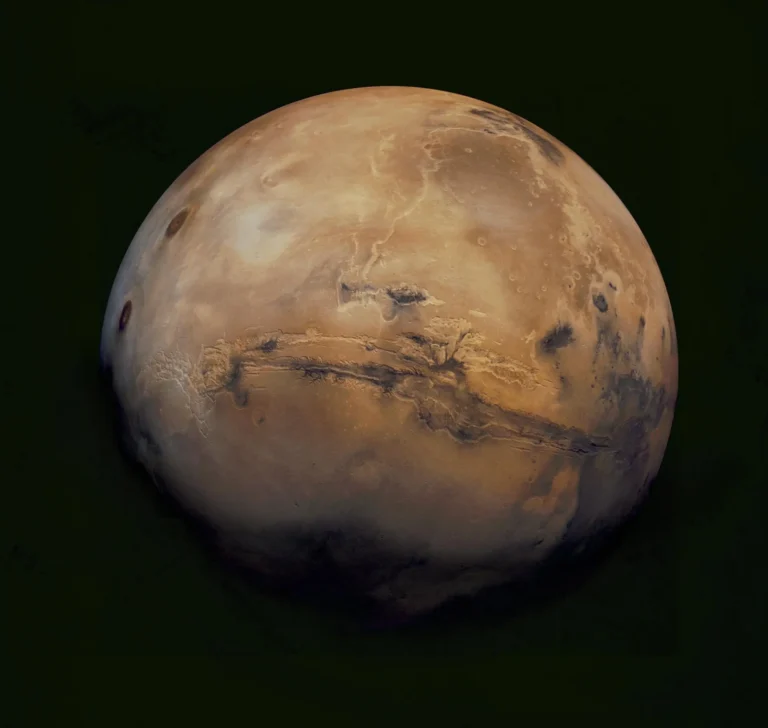

Galileo is remembered first and foremost as a scientist. His father was a skilled musician, teacher, and music theorist who produced several surviving compositions. Galileo’s mother was an educated woman from a well-to-do family who could claim a cardinal among her relatives. In 1581, the young Galileo set off to Pisa to study medicine — more to satisfy his father’s desires than his own. It soon became clear that his real interest was in mathematics; he had also been interested in astronomy from an early age. By the 1590s, he was already drawn to the Copernican model of the heavens, in which the Sun, rather than Earth, is recognized as the center of our system of planets. When a new star appeared in the sky in 1604 — the supernova now known as Kepler’s Star — Galileo delivered a series of lectures on the remarkable object, speculating on its significance.

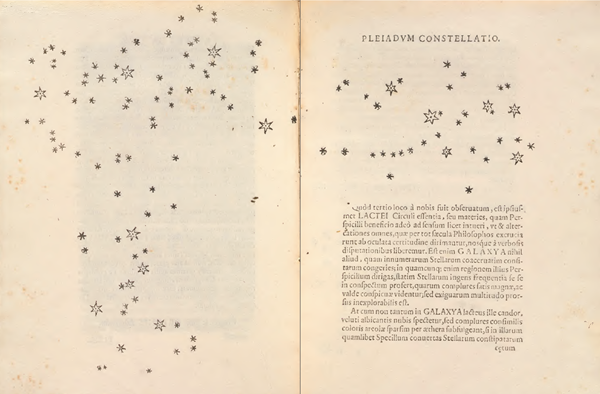

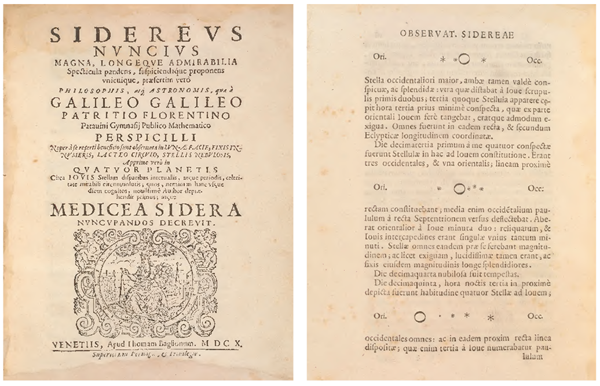

Galileo was teaching mathematics at the University of Padua in 1609 when he learned of a curious optical device from Holland that was said to make distant objects appear as if they were much closer. Improving on the original Dutch invention, Galileo made a device that could magnify 20 or even 30 times. In the fall of 1609 and the winter of 1610, he aimed this instrument at the night sky and made a series of jaw-dropping discoveries. With his telescope, he observed that the Moon has an irregular surface peppered with mountains, craters, and flat plains; that the Milky Way is made up of thousands of stars too faint to see with the unaided eye; and that Jupiter is accompanied by four “stars” seemingly in orbit around the great planet. All of these are recounted in Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger), which Galileo published in March 1610. He would later analyze sunspots and discover that Venus, like the Moon, displays distinct phases.

Physics also commanded Galileo’s attention. Throughout his life, he studied motion — especially accelerated motion — by experimenting with falling bodies and by rolling objects down inclined planes. He also studied what we now call inertia, investigated the strengths of various materials, and developed the modern science of mechanics

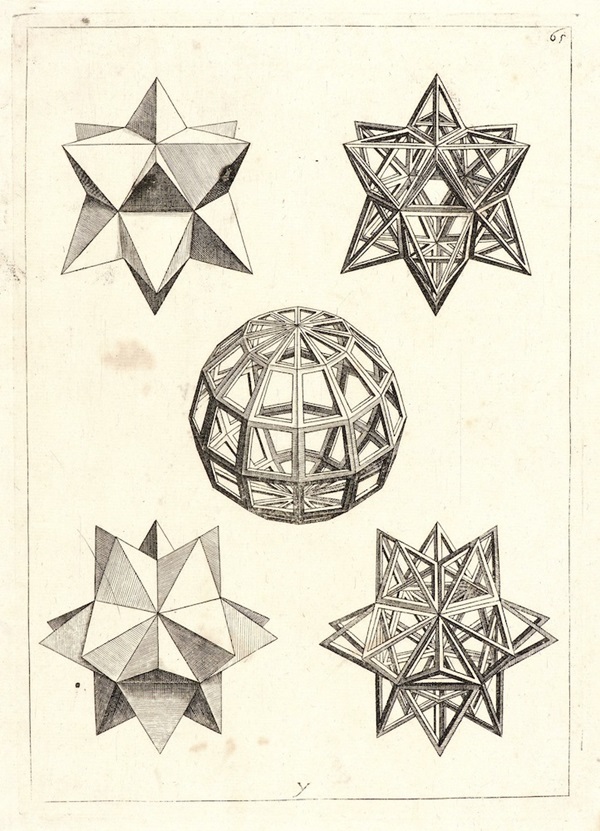

All of these facts paint the traditional picture of “Galileo the scientist.” But he was also a skilled artist, drawing in part from knowledge that he acquired at the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno (Florentine Design Academy), where painters, sculptors, and architects gathered to discuss the intricacies of their profession. Galileo is believed to have studied there in 1585 and was elected to its membership in 1613. At the Academy, he would have been exposed to key ideas such as linear perspective — the technique employed by artists to render objects in three dimensions, developed a century earlier by the architect and designer Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446). Artist and polymath Leon Battista Alberti (1404–72) had produced two lavishly illustrated treatises in which he expounded on the importance of realism and three-dimensionality; it’s likely that Galileo absorbed these ideas.

Galileo also appears to have struck up lasting friendships with some of the leading artists of his day. They often sought out his opinions, recognizing his skill as a draftsman and as a master of perspective. Galileo collected paintings and loaned money to artists, as well. “He really thought of himself as being deeply involved in the art world,” says Eileen Reeves, a professor of comparative literature at Princeton University and the author of Painting the Heavens: Art and Science in the Age of Galileo (Princeton University Press, 1997). “I see Galileo as being very interested in the arts and in visual representation in general.”

Science through art

This specialized knowledge paid off when Galileo first aimed his telescope at the Moon, although he initially struggled to interpret what he saw. While light and dark areas on the Moon are visible to the naked eye, his telescope revealed what appeared to be mountains and valleys. But how could he be sure? After all, he was viewing them from above, as well as from about a quarter of a million miles (384,400 kilometers) away. So, he sketched what he saw and tried to make sense of it. “He must have drawn on the tricks of perspective that he had learned years before,” says Reeves. For Galileo, “drawing was a means of discovery, a form of thinking.”

Galileo paid particular attention to the features visible along the terminator, the line that divides the light and dark parts of the Moon. He noticed how the peaks of mountains on the dark side are lit up first, with the sunlight slowly making its way down their sides. As he observed the play of sunlight on those lunar mountains, Galileo was reminded of familiar sights on our own planet. As he wrote in Sidereus Nuncius, “There is a similar sight on earth about sunrise, when we behold the valleys not yet flooded with light though the mountains surrounding them are already ablaze with glowing splendor on the side opposite the sun. And just as the shadows in the hollows on earth diminish in size as the sun rises higher, so these spots on the moon lose their blackness as the illuminated region grows larger and larger.”

One likely source of inspiration for these insights was a book by Daniele Barbaro called La Pratica della Perspettiva, published in 1569. It contained, among other things, lessons on how to draw spheres — not only perfectly smooth spheres, but also spheres with various protuberances. Another book, Lorenzo Sirigatti’s La Pratica di Prospettiva, published in 1596, contained similar practical instructions. Galileo also sat in on lessons on Euclidean geometry taught by the Florentine mathematician Ostilio Ricci (1540–1603).

These innovations certainly helped artists render the world around them more vividly — but some scholars argue they also could have helped pave the way for the Scientific Revolution itself. Writing in Art Journal in 1984, Samuel Edgerton, an emeritus professor of art history at Williams College in Massachusetts, claimed there is “a clear case of cause and effect between the practice of Italian Renaissance art and the development of modern experimental science.” Edgerton, now 94, says he “absolutely” stands by that assessment more than 30 years later. The key, he says, was the discovery of the idea of “viewpoint” by Renaissance artists. When we look at a set of railway tracks converging toward the horizon, the convergence is not a property of the tracks (which are, after all, parallel), but a property of our minds. The effect “is in your head and in your eyes,” Edgerton says, “and the artists knew that.”

And only someone as skilled as Galileo could see that mountains on the Moon were just like the mountains here on Earth — once he understood the viewpoint from which they were being seen.

A trained artist

Galileo’s depiction of the lunar surface, as rendered in a series of engravings, are one of the highlights of Sidereus Nuncius. Instead of the perfect Moon imagined by the ancients, we see the rugged, pockmarked Moon that we know today. The book’s engravings were preceded by a series of wash drawings — paintings made with a technique in which brown ink is diluted in water so the brushstrokes are nearly invisible, often allowing the underlying paper or canvas to be seen. These drawings, along with some of Galileo’s original notebooks, are now housed in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Florence. Astronomers and historians agree that the drawings are based on observations of the Moon carried out between November 30 and December 18, 1609.

The wash drawings are more than just instructions for the engraver — they are works of art in their own right, says Roberta Olson, an art historian and Curator of Drawings at the New York Historical Society. She describes the wash drawings as “illusionistic studies” that are “artistically superb.” Galileo’s skill at applying the wash, carefully revealing the paper below only in specific areas, required enormous talent, Olson says. “Only a very highly trained and sophisticated artist would know how to do that.”

Edgerton, too, has praised the artistic nature of Galileo’s lunar sketches. In his book The Heritage of Giotto’s Astronomy (Cornell University Press, 1991), he writes: “With the deft brushstrokes of a practiced watercolorist, he laid on a half-dozen grades of washes, imparting to his images an attractive soft and luminescent quality.” Galileo’s use of an “almost impressionistic technique” in rendering lighting effects “reminds us of Constable and Turner, and perhaps even Monet.”

Interestingly, the published drawings that appear in Sidereus Nuncius are quite different from the wash drawings. Most obviously, a gigantic crater larger than any that actually exists on the Moon’s surface figures prominently on the Moon’s terminator as depicted at First Quarter or Last Quarter. (The closest real-life candidate for this oversized feature is a medium-sized crater known as Albategnius; however, either Galileo or his engraver seems to have embellished it almost beyond recognition.) Historians speculate that Galileo gave his drawings to the engraver as a guide but also encouraged him to employ his artistic license, exaggerating certain features to support the accompanying text.

In another light

Another phenomenon that challenged Galileo as both an artist and a scientist was earthshine — the faint illumination of the dark part of the Moon’s face caused by light from the Sun reflecting off of Earth. It is most readily seen in the first few days following New Moon. In Galileo’s time, this ghostly shine, which he referred to as the Moon’s “secondary light,” was far more mysterious.

As he described it in Sidereus Nuncius, “When the moon is not far from the sun, just before or after new moon, its globe offers itself to view not only on the side where it is adorned with shining horns, but a certain faint light is also seen to mark out the periphery of the dark part which faces away from the sun … This remarkable gleam has afforded no small perplexity to philosophers.”

Galileo eventually concluded that the phenomenon originates in light reflected from our own planet, and again, his interpretation may have leaned on his artistic knowledge. The principles of reflected light were already quite familiar to artists. Edgerton points out that Alberti offered a description of the phenomenon not for the Moon specifically, but in terms of general principles, in his treatise Della Pittura (On Painting). Alberti noted that the “reflection of rays always takes place at equal angles” and that such rays “assume the color they find on the surface from which they are reflected. We see this happen when the faces of people walking about in meadows appear to have a greenish tinge.” Artists had long applied Alberti’s logic to depicting terrestrial objects, but Galileo may have been the first to apply it to the heavens.

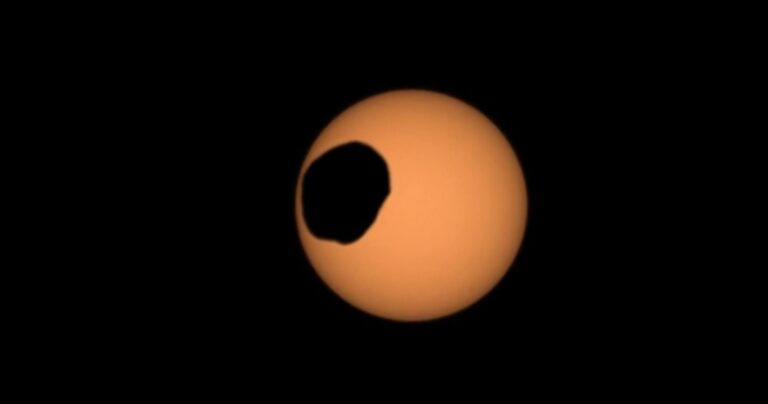

Galileo faced a very different challenge when he aimed his telescope at the great planet Jupiter. He saw four small bodies that appeared to change their positions from night to night, but always remained close to the planet itself. The only reasonable conclusion was that these were moons revolving around Jupiter. But his notebooks reveal that he was struggling to make sense of what he was seeing. For starters, the moons didn’t always appear in a straight line. “At first, Galileo ‘corrects’ his drawings,” says Reeves. “He figures they should be lined up.” But eventually, Galileo concluded that the moons’ orbits around Jupiter must be inclined to our line of sight, and drew the moons as they actually appear in the sky.

Galileo was always drawing, sketching, and painting. “I think he found it hard to think without drawing,” Reeves says. If he was unsure how something ought to be treated, he would ask his artist friends — and they would likely consult him, too. This back-and-forth “was a constant process with Galileo, and with his friends.”

In good company

Evidence that artists held Galileo in the highest regard can be found in a painting by the Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens. In his Self Portrait in a Circle of Friends from Mantua, dating from about 1604, we see six figures: Rubens; his brother; the son of a merchant; the son of a nobleman; a Flemish scholar; and a young man near the center of the canvas, pegged by some historians as Galileo. We know that Galileo was friendly with both Rubens and his brother and that “they probably shared similar philosophical ideas,” says Reeves. It’s also possible that they shared the Copernican view of the cosmos, though this is much harder to prove. If they did, however, then this intriguing painting could be “a sly way of doing it,” without overtly identifying oneself as a Copernican, she says.

Artists were also inspired by Galileo’s astronomical discoveries. Most notable is the painter Lodovico Cardi, better known as Cigoli (1559-1613). Cigoli’s most important commission came when he was asked to paint the chapel of Pope Paul V in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. He began the work that would adorn the inside of the cupola, often called the Immacolata, in September of 1610, and completed it by 1612. The biblical scene it depicts, based on the book of Revelation, shows the Virgin Mary as the Queen of Heaven standing on the Moon, wearing a multicolored robe and carrying a scepter in her right hand. A halo of 12 stars looms above her head; at the bottom we see a coiled serpent.

The fresco’s most striking feature is the lunar surface, clearly pockmarked with craterlike features. Scholars have concluded that Cigoli’s depiction of the Moon is directly indebted to one of the lunar images published in Sidereus Nuncius, in which the Moon is seen at its First Quarter phase. But it is also possible that Cigoli made his own observations, perhaps peering through one of Galileo’s telescopes. “I would think that [Cigoli] had, at the very least, access to a telescope,” says Reeves.

Interestingly, while the traditional Aristotelian view of the Moon was that of an unblemished, perfectly spherical body, Cigoli appears to have had no hesitation in depicting it as irregular and mountainous, just as Galileo had. While Galileo would be hauled before the Inquisition some 20 years later in 1633 — in part for his vocal support of Copernican astronomy — the Catholic authorities do not seem to have been particularly bothered by Cigoli’s bold depiction of the Moon.

Clearly, Galileo was much more than a single-minded man of science; rather, he was a polymath with artistic leanings that deserve greater attention. Those artistic skills helped him beyond measure as he struggled to comprehend the sights revealed by his telescope and to communicate those sights to a mass audience.

“It was all about discovery,” says Olson. “Discovery of the physical world, discovery of the principles that make it work.” The scientists of Galileo’s day, as well as the artists, wanted “to see how the cosmos worked.”