Key Takeaways:

I’ll admit it: I am an addict. I am hooked on vintage astronomy books. One of my favorites is Astronomy With an Opera-Glass by Garrett P. Serviss, first published in 1888. Serviss, a newspaper reporter by trade, was a prolific author of the late 19th and early 20th century. He wrote nine astronomy books for backyard stargazers, as well as six lesser-known science-fiction books. His words describing this month’s target are a perfect way to introduce one of my favorite springtime sights:

“The three [stars], Denebola, Spica, and Arcturus, mark the corners of a great equilateral triangle. Nearly on a line between Denebola and Arcturus, and somewhat nearer to the former, you will perceive a curious twinkling, as if gossamers spangled with dew-drops were entangled there. This is the little constellation called Berenice’s Hair.”

Historically, Berenice II was queen of Egypt, married to Ptolemy III Euergetes. Around 240 B.C., after her husband left to fight a particularly dangerous battle against the Seleucid Empire in western Asia, Berenice vowed to the goddess Aphrodite that if Ptolemy returned safely from battle, she would cut off her flowing hair and place it in the goddess’ temple. He did, so she did. But the hair mysteriously disappeared. Thinking quickly on his feet, their court astronomer Conon calmed the royal couple by pointing toward a hazy glow in the sky between Denebola and Arcturus. He announced that the mist seen faintly by eye was actually Berenice’s hair, transformed by Aphrodite and placed among the stars.

Berenice’s Hair, more formally known as Coma Berenices, is a faint constellation by eye, composed of only three modest naked-eye stars set in a right triangle. But what catches our eyes under darker skies is also a faint glow west of those stars. No, that misty glow is not the transfigured tresses of the ancient queen’s hair. That glow is actually an open star cluster lying 280 light-years from Earth.

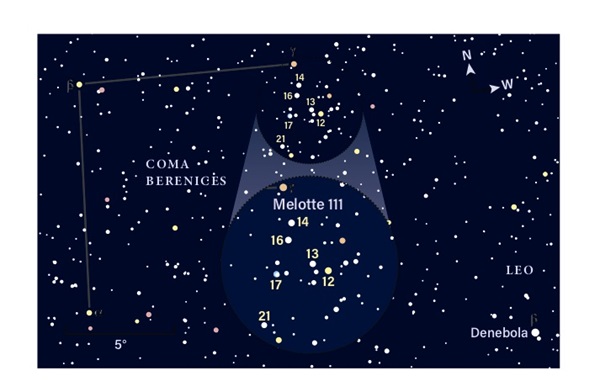

The Coma Star Cluster, known more formally as Melotte 111, often goes unnoticed through telescopes but is perfect for binoculars. That’s because the cluster spans 5° of sky, far more than a telescope can drink in at once. Its stars are also quite scattered, making it difficult to appreciate the cluster even with a careful telescopic scan.

According to Star Clusters by Brent Archinal and Steven Hynes (Willmann-Bell, 2003), over 270 stars populate the Coma Star Cluster. Of those, about 40 shine brighter than 10th magnitude. Many are easily within range of pocket binoculars and a half-dozen even break the naked-eye barrier under dark skies.

Although I can’t make out individual stars by eye from my suburban backyard, I do get a “mystical” sense to the east of Denebola (Beta [β] Leonis). When I raise my old 7×50 wide-field binoculars its way, the Coma Star Cluster immediately pops into view. Although it is not as jam-packed with stars as some open clusters in the summer or winter skies, this is always one of my first stops when I head out this time of year.

The first thing that strikes me is the cluster’s distinctive shape. Those five brightest stars are arranged in arcs and lines that collectively remind me of a V-shaped skein of northward-flying geese. Others see a lower-case Greek lambda (λ) or an inverted V.

The cluster’s brightest star is not Gamma (γ) Comae Berenices, despite its prominent position at the northern edge of the cluster. Although it adds some color to the scene, Gamma, an orange type K star, lies in the foreground 170 light-years away. The brightest true cluster stars include 12, 13, 14, 16, and 21 Comae Berenices.

Several stellar pairings highlight the Coma Cluster. Of these, 17 Com, just east of the cluster’s center, is the most striking. Even the smallest opera glass will have no trouble resolving 17’s 7th-magnitude companion, found 2.5′ to its west-southwest.

Do you have a favorite star cluster or some other binocular target that you enjoy revisiting? Drop me a line in care of my website, philharrington.net, and tell me about it.

Until next month, remember that two eyes are better than one.