Less than 48 hours later, Venus passes between the Sun and Earth. This is Venus’ second solar transit in the past eight years but the last one until 2117. Observers nearly everywhere except eastern South America and western Africa will be able to watch at least part of this rare and historic event.

Following the transit, Venus moves into the morning sky and pairs with Jupiter in some spectacular predawn scenes. The evening sky has its own charm, with Mercury on display during twilight and Mars and Saturn prominent after darkness falls. Meanwhile, Pluto reaches opposition and peak visibility in late June. Although you will need a telescope to see the distant world, its position near a relatively bright star makes the task of finding it a bit easier than usual.

Let’s begin our tour in the western sky shortly after sunset. Mercury puts on a fine display starting the second week of the month. On June 7, the innermost planet lies 6° above the west-northwestern horizon 30 minutes after the Sun goes down. It then shines at magnitude –1.0, which is plenty bright enough to show up against the twilight sky. If you can’t spot it immediately with naked eyes, sweep just above the horizon with binoculars. A telescope reveals a 5.5″-diameter disk that looks nearly full (85 percent lit).

Mercury climbs higher as the month progresses, so it appears against a darker sky. Although the planet fades noticeably during June, its greater altitude helps its visibility. Mercury reaches greatest elongation on the 30th, when it lies 26° east of the Sun.

The planet’s telescopic appearance changes quickly during June. Its apparent diameter grows to 7.9″ by month’s end while its phase dwindles to 42 percent lit. The planet then glows at magnitude 0.4.

On June 1, Mars lies the width of a Full Moon southeast of the 5th-magnitude double star Chi (χ) Leonis. On the 27th, the planet stands less than half that distance southwest of another double, 4th-magnitude Beta (β) Virginis.

Mars reached opposition in early March. In the three months since, our planet has moved progressively farther away, so Mars now appears fainter and smaller. The Red Planet fades from magnitude 0.5 to 0.8 and its disk shrinks from 7.9″ to 6.6″ across during June. You likely will need a 10-inch or larger telescope to see any dusky surface markings, although the white polar cap should still stand out.

The gap between Mars and Saturn shrinks from 38° to 24° during June. And the two planets essentially match each other’s brightness this month. The ringed planet’s slightly yellowish color helps set it apart from its planetary cousin.

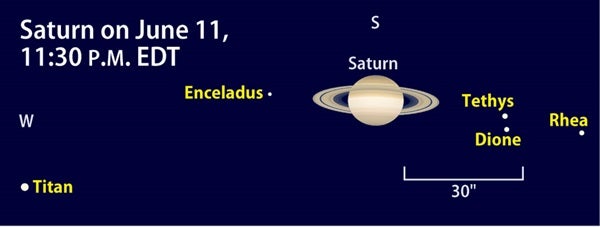

Saturn is a stunning object in the late evening through almost any telescope. (Try to catch it by midnight, when it starts to sink closer to the western horizon.) In mid-June, the planet displays an 18″-diameter disk wrapped by a ring system that spans 41″. The rings tilt 12.5° to our line of sight — their minimum angle of 2012. They begin to widen by month’s end, a trend that will continue into next year. Still, the 12.5° tilt provides great views of the rings’ northern face. Also look for the planet’s shadow falling on the rings behind Saturn, just off the planet’s eastern limb.

The ringed planet also hosts several bright moons. Eighth-magnitude Titan, which is larger than the planet Mercury, circles Saturn once every 16 days and is easy to see through any scope. It passes due south of the planet June 5 and 21 and due north June 13 and 29.

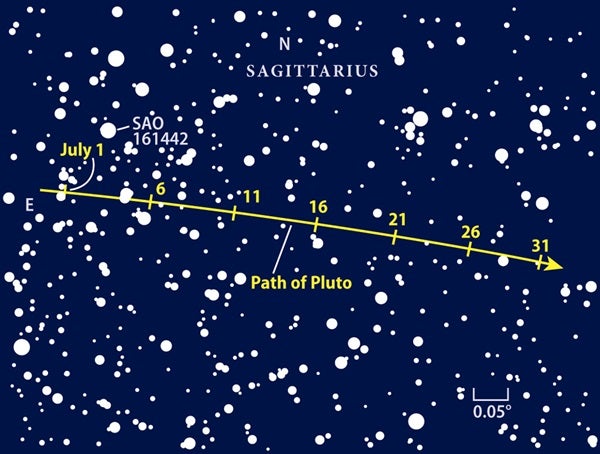

Pluto reaches opposition June 29. On that date, the distant world lies opposite the Sun in our sky (the month’s third syzygy), so it remains visible all night. Pluto also shines brightest at opposition, although, at magnitude 14.0, “bright” is not the most descriptive term. You’ll need a dark transparent sky and an 8-inch telescope with good optics to spot it visually, and a larger instrument certainly helps.

Pluto does pass near a relatively bright guide star, however, which makes the task of finding the correct field of view much easier. On June 1, the distant world lurks near a line of 7th-magnitude stars, the brightest of which is cataloged as SAO 161665. These stars lie a little more than 1° due east

of the open star cluster M25 in Sagittarius. (The cluster lies just outside the field shown in the finder chart on page 43.) By June 17, Pluto passes just 2′ south of the 7th-magnitude star SAO 161635. A series of CCD images taken through a 4-inch or larger scope over three nights on either side of June 17 will reveal Pluto. You then can create your own movie file of the dwarf planet’s motion.

Shortly after the clock strikes midnight, Neptune pokes above the eastern horizon. But you’re better off searching for the planet once it climbs higher an hour or so before dawn begins. Glowing at magnitude 7.9, Neptune is within reach of binoculars. Mount them on a tripod for the steadiest views — even slightly unsteady hands will reduce what you can see by a magnitude.

Neptune lies some 3° south-southeast of the 4th-magnitude star Theta (θ) Aquarii. The planet appears stationary relative to the background stars June 4/5, but it barely changes position during the rest of the month. When viewed through a telescope, Neptune shows a blue-gray disk that measures 2.3″ across.

Uranus stands about 20° above the eastern horizon as twilight begins in mid-June. Although this world resides among the background stars

of Cetus the Whale, it appears even closer to the pattern that forms Pisces the Fish. The magnitude 5.9 planet lies in the same binocular field as 44 Piscium, a star about as bright as the planet and located 1.5° to its west-southwest. Turn your telescope toward Uranus, and you’ll find a 3.5″-diameter disk with a distinct blue-green color.

Venus climbs quickly into the morning sky after the transit. As it emerges into bright twilight around midmonth, it finds Jupiter there to greet it. The gas-giant planet, which returned to the eastern sky before dawn in early June, grows more prominent with each passing day.

On June 14, it pokes above the horizon more than an hour before the Sun. A crescent Moon rises some two hours earlier and serves as a guide to the planet. Venus rises 40 minutes after Jupiter in the rapidly brightening sky.

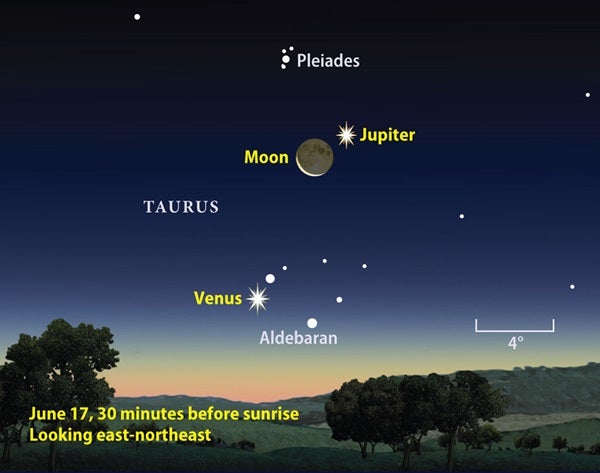

The waning crescent Moon drops closer to Jupiter with each passing day. Less than 2° separate the two June 17; Venus then hangs 7° to the Moon’s lower left. The scene will be stunning with naked eyes or binoculars, but the extra light-gathering ability of binocs also should reveal the Pleiades star cluster (M45) some 5° above Jupiter. That morning, Venus gleams at magnitude –4.2 while Jupiter shines at magnitude –2.0.

Jupiter’s low altitude this month keeps it from showing much detail through a telescope. Don’t expect to see more than its two dark equatorial belts spanning a 33″-diameter disk.

Venus tells a different story, however. The inner planet never shows any surface or atmospheric detail, but it does display dramatic changes in size and phase. On June 20, its disk appears 52″ across but only 7 percent illuminated. By the 30th, its diameter has shrunk to 45″ while its phase has thickened to 16 percent lit. Venus then rises nearly two hours before the Sun and shines at magnitude –4.6 among the background stars of the Hyades star cluster in Taurus the Bull.

The final event of this busy month is a partial lunar eclipse on June 4. In North America, the eclipse occurs before dawn. Earth’s umbral shadow takes its first bite from the Moon at 6:00 a.m. EDT (3:00 a.m. PDT). This is after the Moon sets in the continent’s northeastern part, but everyone else can see at least part of the event. Maximum eclipse comes at 4:04 a.m. PDT, when 37 percent of the Full Moon will be darkened by our planet’s shadow. The eclipse wraps up at 5:07 a.m. PDT.

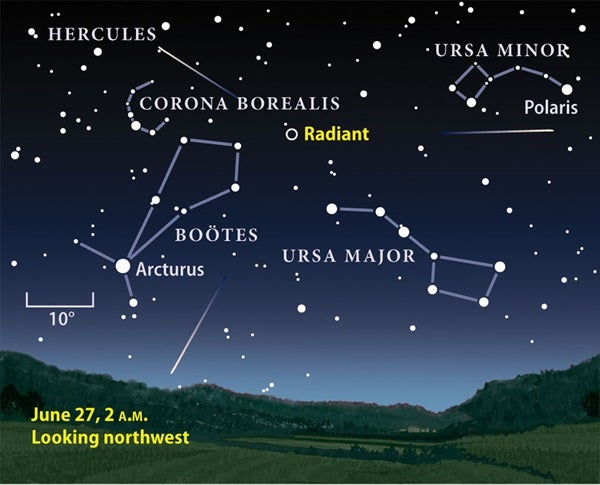

The typically minor June Boötid meteor shower occasionally has delusions of grandeur. After decades of inactivity, the shower returned in force in 1998, when observers witnessed up to 100 meteors per hour. Rates about half that high appeared in 2004. Although astronomers aren’t predicting an outburst this year, veteran viewers will keep their eyes to the sky for a few days around the Boötids’ June 27 peak.

Observing conditions should be excellent. The First Quarter Moon sets shortly after midnight, leaving the prime hours before dawn Moon-free. The meteors appear to emanate from a point, called the “radiant,” in the northern part of Boötes the Herdsman. These cosmic vagabonds stand out because they move so slowly, entering Earth’s atmosphere at “only” 11 miles per second.

To many newcomers, Full Moon seems like the best time to view our satellite. After all, its entire Earth-facing hemisphere is bathed in sunlight and nothing hides in the shadows. A few looks at a Full Moon through a telescope quickly changes that perception — those very shadows provide a depth and contrast that gets washed out when the Sun shines nearly straight on.

But this doesn’t mean you should pack away your scope when the Moon waxes toward Full. There are still plenty of areas worth exploring. The first week of June and July deliver great views this year.

The terrific ray system emanating from the crater Tycho dominates the Full Moon. These bright streaks — debris thrown out by the massive impact that created this crater — fan out across much of the lunar nearside. Scientists know they formed in the relatively recent past because the incessant solar wind darkens them over time.

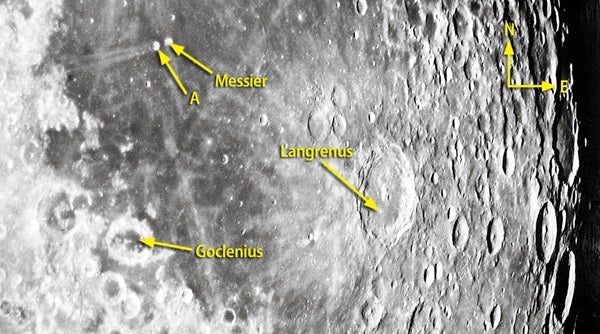

Let’s follow one of Tycho’s long rays to Mare Fecunditatis, the Sea of Fertility. This ray first crosses Mare Nectaris, where it practically pierces the small crater Rosse. Then, after passing some highlands, the ray seems to skip over the perfectly round, lava-filled crater Goclenius near the western edge of Mare Fecunditatis. The streak then picks up again and continues across the rest of the mare. Did the higher elevations of the highlands and crater rims produce “ray shadows” where no ejecta material fell? Astronomers still don’t know the answer.

On the mare’s opposite shore, numerous short rays spread out from the crater Langrenus like spokes on a bicycle wheel. But the coolest rays in Fertility are just north of the sea’s center: a pair of parallel rays shooting from the double crater Messier and Messier A.

| When to view the planets | ||

| EVENING SKY | MIDNIGHT | MORNING SKY |

| Mercury (northwest) | Mars (west) | Venus (east) |

| Mars (southwest) | Saturn (southwest) | Jupiter (east) |

| Saturn (south) | Uranus (southeast) | |

| Neptune (southeast) | ||

Our nearly constant companion over the past year, Comet C/2009 P1 (Garradd), is now fading rapidly. It should hold at 10th magnitude in early June but may be down to 11th magnitude later in the month as it moves steadily away from both the Sun and Earth. You’ll likely need a 6-inch telescope and a dark sky to pick up the small fuzzball and any short tail it may have left.

Comet Garradd lies in eastern Cancer, not far from its border with Leo. This region lies highest soon after darkness falls. Here, background stars are like grains of sand on a celestial beach — there are plenty of them and they look much alike. The most recognizable guideposts are the 5th-magnitude stars Nu (ν) and Xi (ξ) Cancri. Be patient, ensure you are dark adapted (keep your observing eye closed while checking the finder chart), and confirm the star patterns as you close in on the comet.

In the likely event you can’t see it at low power, don’t panic. Pop in an eyepiece that gives around 120x and use averted vision (by looking to the side of the field) while gently tapping on the scope. Our eyes evolved to detect faint things when they move.

Next month, Comet 96P/Machholz zips through the inner solar system. If we’re lucky, it may put on a quick binocular show in evening twilight. And for Internet users, it should cross the field of view of the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory in mid-July.

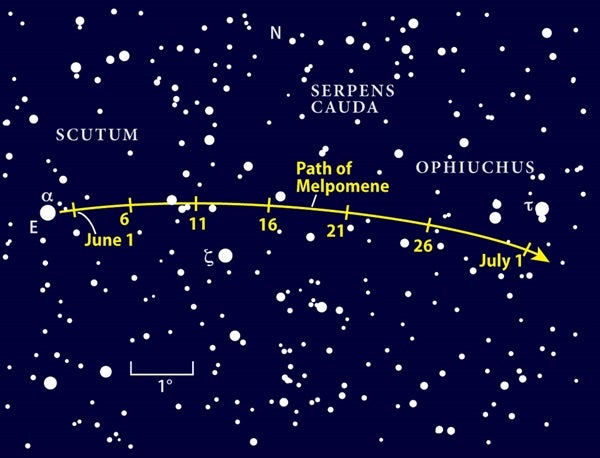

Trying to identify wildlife is much easier when an animal moves out of the forest and into a clearing. We can spot the main-belt asteroid 18 Melpomene as it does the celestial equivalent in June. The space rock crosses from Scutum the Shield into Serpens the Serpent this month, a region that lies in the southeastern sky in late evening.

The magnitude 9.8 asteroid slides away from the camouflage provided by the rich Milky Way backdrop in Scutum. Once the Moon has left the evening sky in the second week of June, Melpomene resides in an open area among a handful of background suns just 1° north of 5th-magnitude Zeta (ζ) Scuti. Its night-to-night shift against these distant beacons duplicates the method Englishman John Hind used to discover the asteroid in 1852.

The meager smattering of stars here is not really a clearing, but an obscuring veil of dust and cold gas in front of the distant Milky Way throngs. This dark nebula is a close cousin to the more famous Horsehead Nebula in Orion the Hunter and the Great Rift that splits the Milky Way in half in Cygnus the Swan.

Martin Ratcliffe provides professional planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. Alister Ling is a meterologist for Environment Canada.