Of the solar system’s eight major planets, only two show up easily this month. Jupiter blazes high in the sky and will be the major planetary attraction on March evenings. Saturn rises before midnight and stands out a few hours later. The rest of the planets lie far closer to the Sun throughout March.

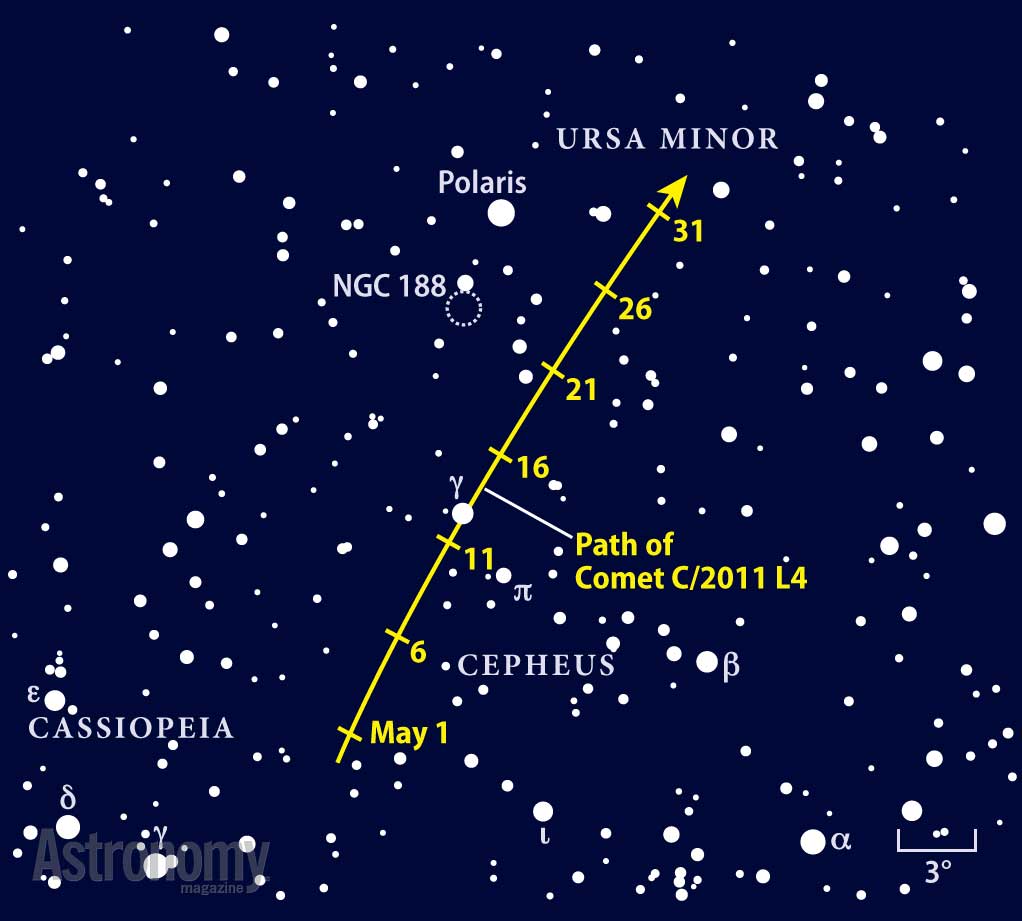

Let’s begin our tour of the solar system with Comet C/2011 L4 (PANSTARRS) and its potential for making this month memorable. It reaches perihelion (its closest point to the Sun) March 9, when it lies 28 million miles from our star. It should shine brightest around then, peaking perhaps at magnitude 0 or –1 if astronomers’ predictions hold true.

It likely won’t be easy to spot until a few days later, however. On March 12, look due west a half-hour after sunset, and you should see a slender crescent Moon hanging some 8° above the horizon. The comet’s head, or coma, lies just 4° to its left in the sky. You’ll likely have to wait for twilight to deepen before the coma comes into view, and you still may need binoculars. But if luck is on our side, the comet will show up easily. Then, as the sky darkens, the comet’s dust tail should come into view. Even if PANSTARRS fizzles somewhat, the binocular view still should be impressive.

If the comet develops a long tail, March 13 will be a night to treasure. The waxing crescent Moon then lies in line with the gas tail. For complete details on viewing the comet, see “Get ready for Comet PANSTARRS” (p. 60).

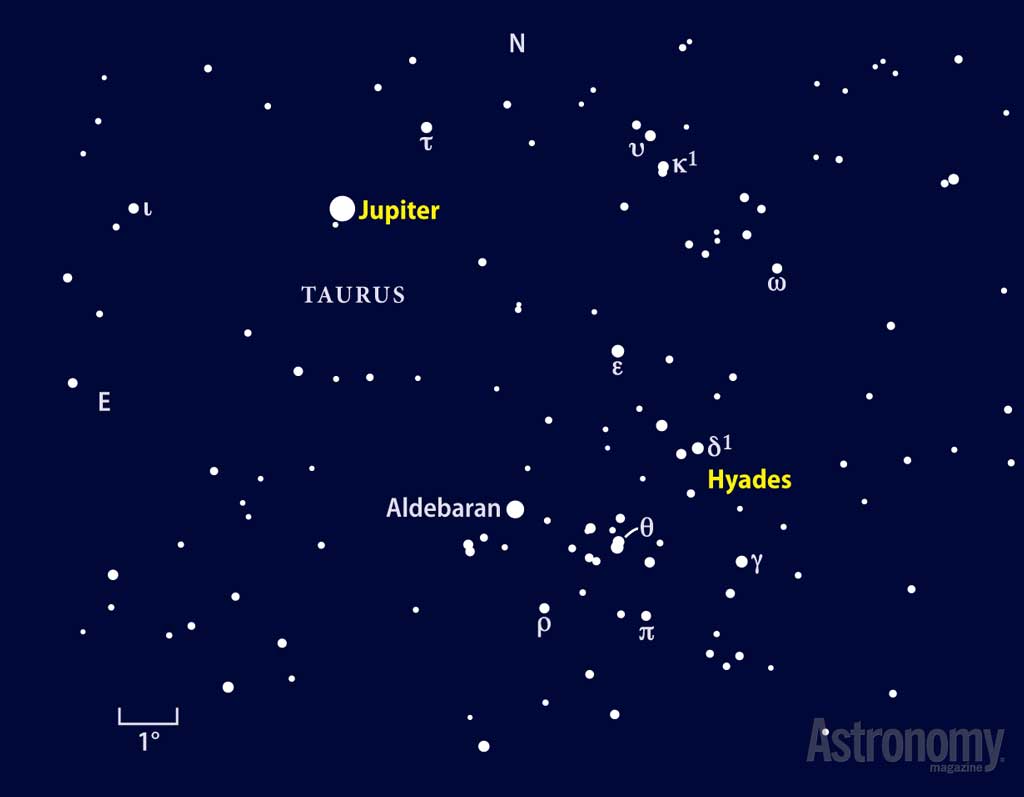

The solar system’s two largest planets, Jupiter and Saturn, are the only ones visible in a dark sky this month. Jupiter appears far brighter, shining at magnitude –2.3 March 1 and fading just 0.2 magnitude by month’s end. The giant planet currently lies against the backdrop of Taurus the Bull. Be sure to grab your binoculars and enjoy the stunning sight of Jupiter flanked by the Pleiades (M45) and Hyades star clusters.

Jupiter and its four Galilean moons provide many other notable events this month. On the evening of March 1, Ganymede’s large shadow falls on the jovian atmosphere starting at 9:46 p.m. EST, while Europa begins its own transit of the planet’s disk 17 minutes later.

On March 2/3, Io’s shadow marches across the jovian disk behind the innermost moon. Io first touches the planet’s eastern limb at 10:04 p.m. EST, followed by its shadow at 11:22 p.m. The moon exits the disk at 12:14 a.m., while the shadow lingers 79 minutes longer.

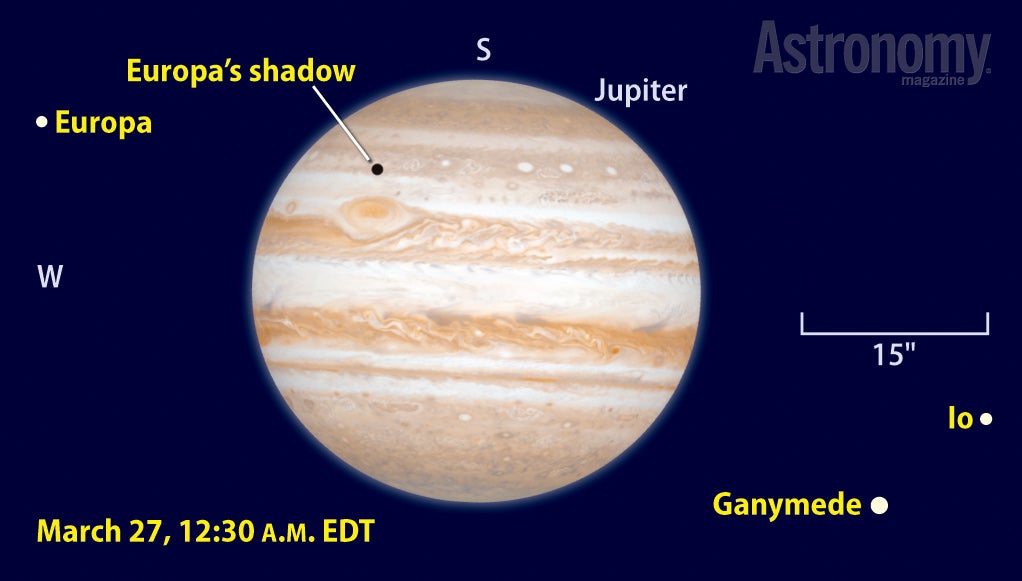

Perhaps the most intriguing series of events occurs the night of March 26/27. For a brief period of time, Jupiter appears to have just one moon. Callisto lies far west of the planet and is the only one visible all night. As darkness falls across the eastern half of North America, however, Jupiter blocks both Io and Ganymede from view while Europa transits the planet’s disk.

Ganymede starts to reappear from behind the planet’s northeastern limb at 10:12 p.m. EDT. At 10:43 p.m., Europa’s shadow begins a transit, and five minutes later, Europa exits the disk. Although Io leaves the planet behind soon thereafter, you won’t see it because Jupiter’s giant shadow envelops it in darkness. The moon moves out of eclipse at 12:04 a.m., when it appears well east of the jovian disk. Io gradually brightens to full luminosity a few arcseconds southeast of Ganymede. From then until Jupiter sets, the three inner moons cluster near the planet.

Saturn rises before midnight local time all month and becomes prominent in the southeast shortly thereafter. It shines at magnitude 0.3 in mid-March and ranks among the brightest objects in the sky. The ringed planet lies among the dim background stars of western Libra the Balance, slightly less than 20° east of 1st-magnitude Spica, Virgo’s brightest star.

Although the ringed planet will reach opposition and peak visibility in late April, the views of it through a telescope this month won’t be much different. The main change is that you’ll have to wait until early morning for Saturn to climb high enough to deliver crisp views. In mid-March, the planet’s disk measures 18.3″ across the equator but only 16.7″ through the poles. This difference is noticeable and arises from a combination of Saturn’s rapid rotation and gaseous nature.

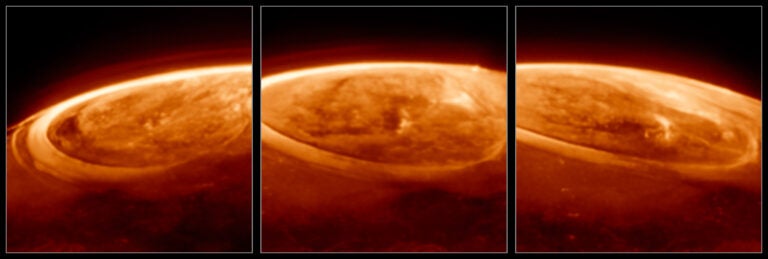

Saturn’s atmosphere usually doesn’t show more than a few pale bands. High-altitude haze hides the deeper cloud layers where activity normally occurs. Large storms occasionally punch through the haze layer, however. A white spot typically heralds the start of such a storm.

Of course, few observers spend a lot of time examining the planet’s disk — the rings are just so magnificent. The ring system spans 41″ and tilts 19° to our line of sight in March. The outer A ring, the brighter B ring, and the dark Cassini Division that separates the two all appear clearly through any size telescope. Under good conditions, you also might spot the innermost C ring. The planet’s limb often shows through this semi-transparent region.

Although Saturn’s moons appear fainter than Jupiter’s quartet, several show up to discerning eyes. Titan glows at 8th magnitude and will look obvious through any size instrument. This large moon passes due south of Saturn March 4 and 20 and north

of the planet March 12 and 28. Saturn’s trio of 10th-magnitude satellites — Tethys, Dione, and Rhea — typically show up through 4-inch scopes. Each orbits closer to the planet than Titan.

Intriguing Iapetus varies in brightness because one hemisphere reflects more than 90 percent of the sunlight that hits it while the opposite side reflects less than 10 percent. It brightens to 10th magnitude when it lies far west of Saturn but dims to 12th magnitude when it’s well east. Iapetus reaches greatest western elongation March 13 and should be fairly easy to spot 9′ from the planet.

You might spy Uranus on one of the first evenings of March. It sets two hours after the Sun on the 1st and appears 6° high in the west 90 minutes after sundown. You’ll need binoculars or a telescope to see this 6th-magnitude world.

Ten days later, Uranus takes part in the closest planetary conjunction in several years. Mars passes 43″ north of Uranus on March 22, but the pair lies just 6° east of the Sun and will be hopelessly lost in its glare. Unlike Uranus, Mars stays close to our star all month and doesn’t put in any appearance.

Uranus passes on the far side of the Sun on March 28, coincidentally just eight hours after Venus does. Uranus then lies 0.7° south of our star, and Venus is the same distance south of Uranus. Like Mars, Venus remains too close to the Sun’s glare to see throughout March.

On March’s final morning, you should be able to find Mercury and perhaps catch a glimpse of distant Neptune. Mercury reaches greatest elongation on the 31st, when it lies 28° west of the Sun. Unfortunately, the innermost planet doesn’t climb high for observers at mid-northern latitudes. Mercury lies 5° above the eastern horizon 30 minutes before sunrise. It shines at magnitude 0.2, however, bright enough to show up against the twilight sky.

Neptune appears a bit higher than Mercury but much fainter. It glows at 8th magnitude from a spot 7° high in the east-southeast 45 minutes before the Sun comes up. Viewers with transparent skies and plenty of patience might try to track down the distant world through binoculars or a telescope.

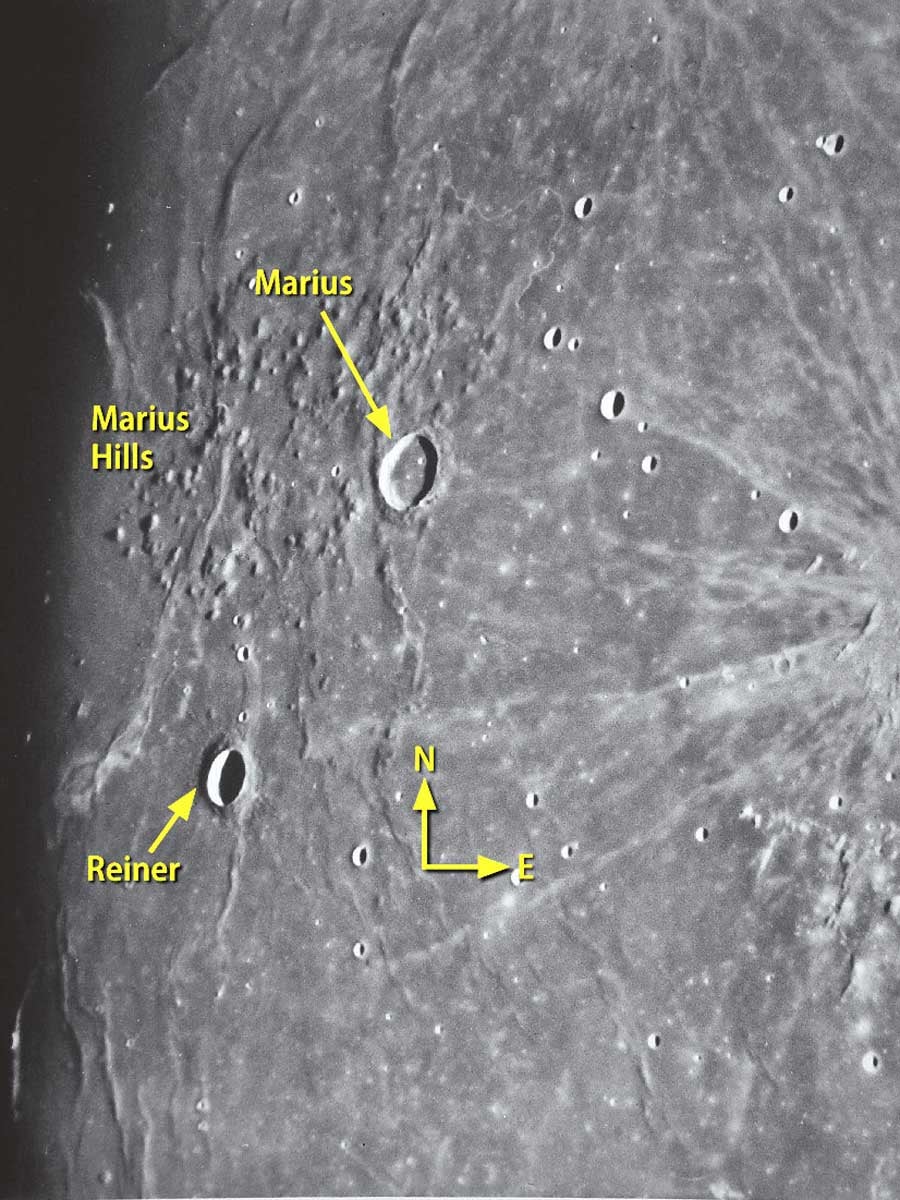

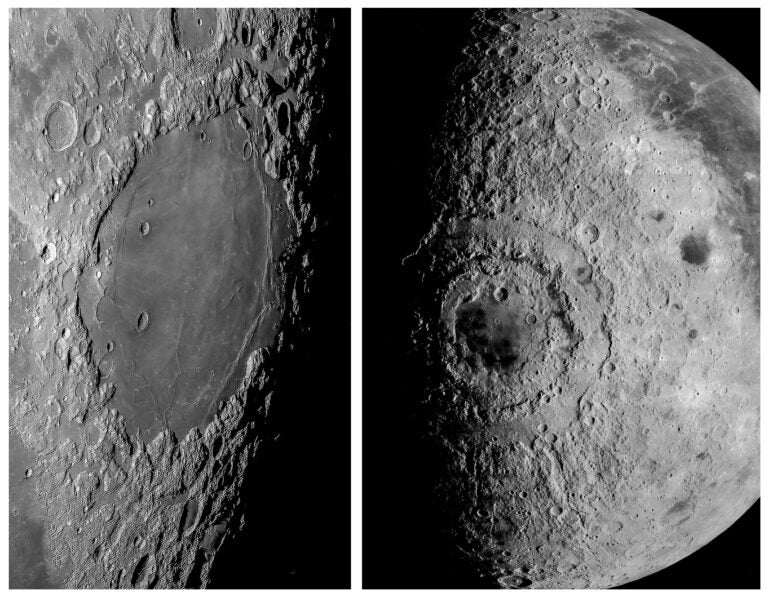

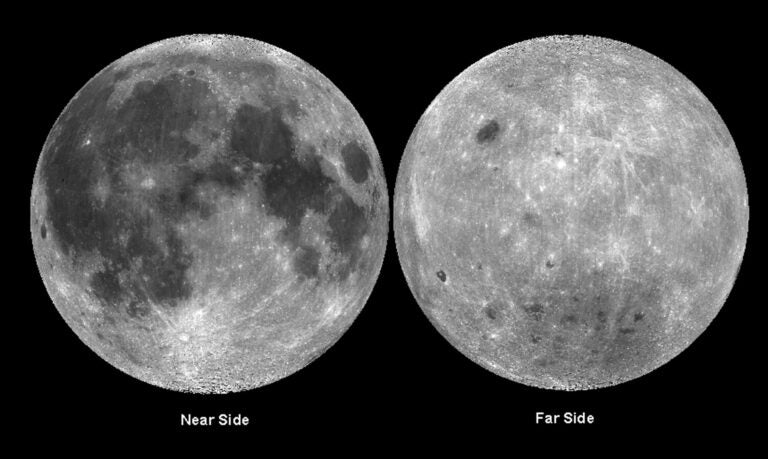

The best volcanic features on the Moon’s face are the lava-filled circular basins called maria (Latin for “seas”). But the field of volcanic domes known as the Marius Hills makes a good second choice. Located in the vast Oceanus Procellarum, the hills appear as coarse, sandpaper-like terrain near the craters Marius and Reiner. This region sees first light about three days before Full Moon.

The Moon shines brightly the evening of March 23, and an inexpensive filter (even sunglasses) will help reduce the glare. Tycho’s spectacular ray system will first draw your attention, and then brilliant Aristarchus in the north will catch your eye. Enjoy them for a few minutes before shifting your gaze to the Marius Hills. The area lies along the terminator — the dividing line between light and dark on the surface — just north of the lunar equator and west of the bright rays emanating from the relatively young crater Kepler.

Boost the magnification for a good look, and then think about how the Moon developed this outbreak of hives. The evidence points to a few episodes of volcanism. First, a few hundred steep-sided volcanoes erupted when a huge zone of magma welled up from below. Less violent eruptions then built the dome structures that surround them. Finally, lava oozed out of cracks and filled much of Oceanus Procellarum. The huge expanse of darker, smoother terrain convinced early observers to call it an ocean.

The Marius Hills become harder to see March 24, and by the 25th, the Sun’s higher elevation wipes out the shadows necessary to view the textured terrain.

March features no major meteor showers, and the only minor one — the Gamma Normids — lies deep in the southern sky and out of the reach of northerners. Yet this month offers a chance to view millions of meteoroids whose combined glow gives rise to the zodiacal light.

The Sun illuminates these tiny bits of dust that orbit in the solar system’s plane, or what astronomers call the “ecliptic.” The zodiacal light shows up best when the ecliptic inclines steeply to the horizon, as it does in March after darkness falls in the Northern Hemisphere.

You need to look for the faint glow from a dark site. And try during March’s first two weeks when the Moon is gone from the evening sky. The cone-shaped glow extends from the western horizon up through Aries and into Taurus.

| When to view the planets | ||

| EVENING SKY | MIDNIGHT | MORNING SKY |

| Jupiter (southwest) | Jupiter (west) | Mercury (east) |

| Uranus (west) | Saturn (southeast) | Saturn (southwest) |

| Neptune (southeast) | ||

It’s time to get ready for what should be a delightful comet. Even grizzled amateurs who think they’ve seen it all are looking forward to seeing Comet C/2011 L4 (PANSTARRS). At its peak just before midmonth, the comet will be set against a deepening azure sky. If predictions hold, it could show a small, bright core that lies close to the horizon with the pale blue flame of its gas tail slanting upward and a feathery whitish plume from its dust tail curving to the left.

The apparition begins with a tease about 50 minutes after sunset March 7. Observers looking just south of due west should see a pale glow extending to the upper left that looks like a jet contrail. A day later, the comet’s compact yellow-white head will appear above the horizon. Each night thereafter, the comet climbs higher into a darker sky, the gas tail’s angle to the horizon grows more vertical, and the expanding dust tail fans to the left. Observers at higher latitudes will see the same progression but delayed by one to two nights.

Unfortunately, the Moon’s light gets worse after the 12th and will partially obscure the delicate tails that should continue to grow. By the time the Full Moon leaves the evening sky in late March, PANSTARRS likely will have faded to 4th magnitude — although that’s nothing to complain about! For more information on viewing the comet, see “Get ready for Comet PANSTARRS” (p. 60).

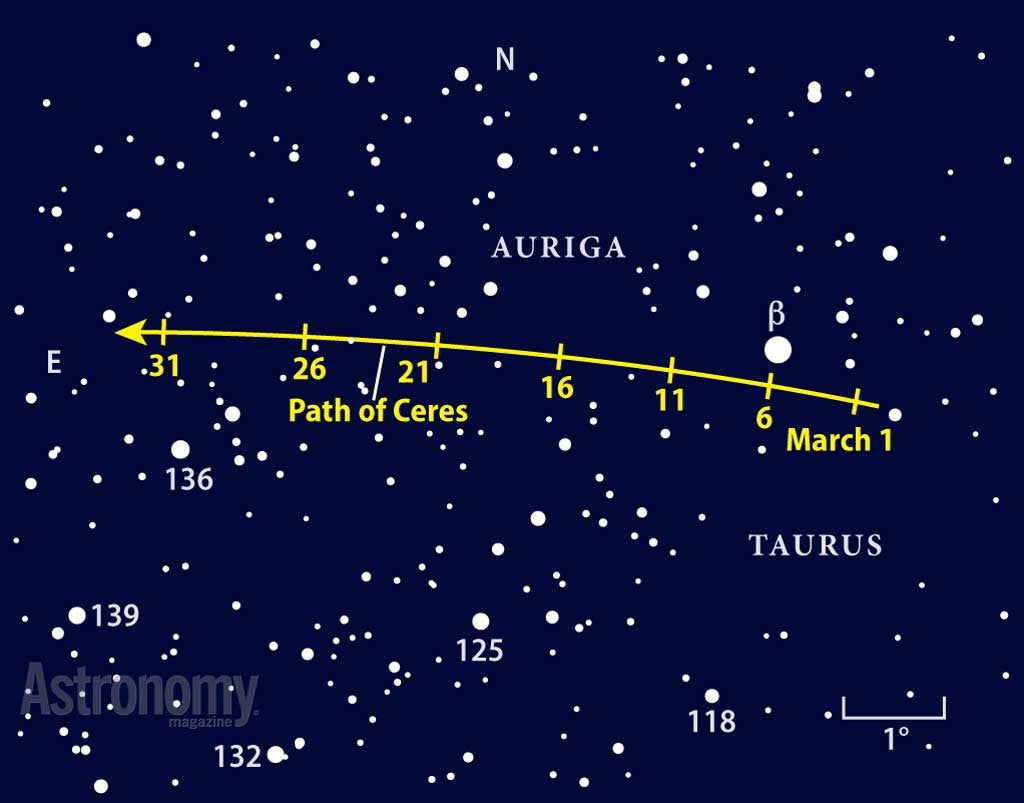

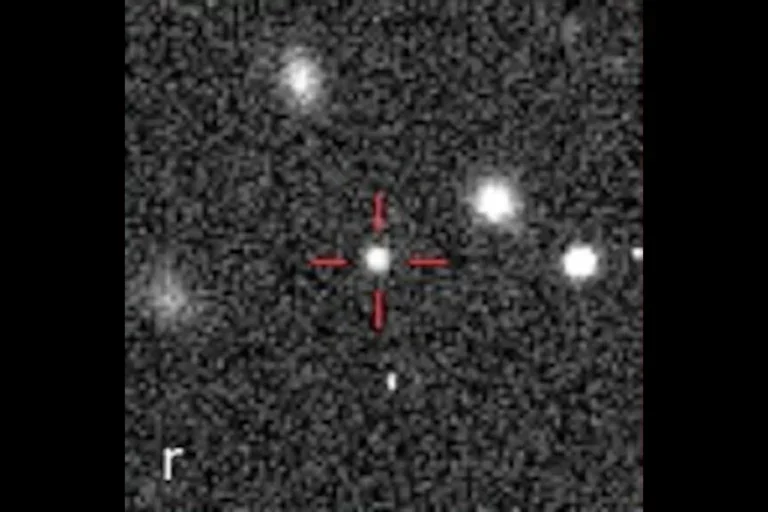

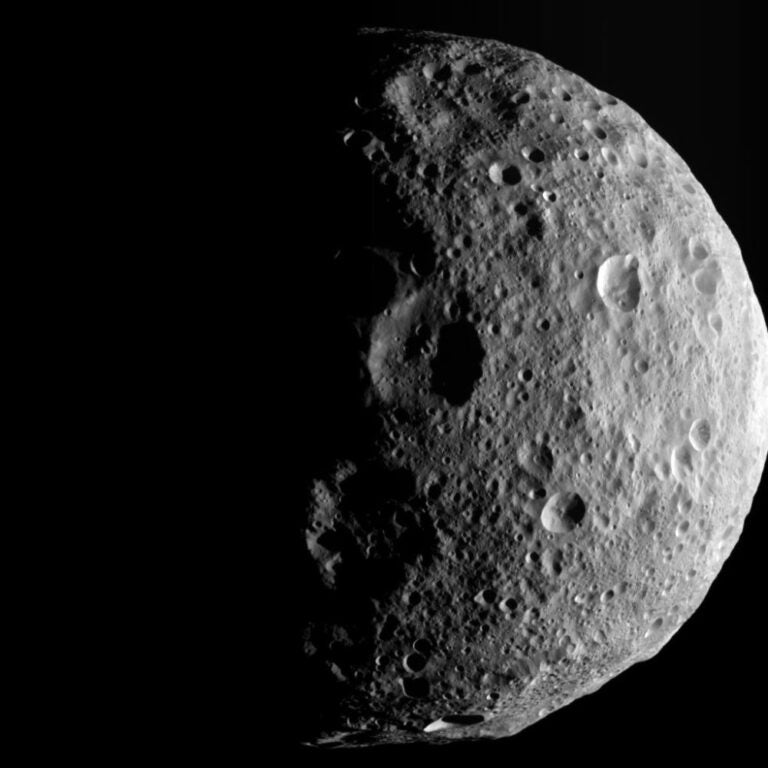

Bagging the dwarf planet Ceres doesn’t get much easier than this. The king of the asteroid belt passes less than 1° from the bright star El Nath (Beta [β] Tauri) this month, and through a telescope it will appear as the first “star” south of Beta. Magnitude 1.7 El Nath represents the northern horn of Taurus the Bull, a constellation that lies high in the southwest after darkness falls.

Although it spans slightly more than 600 miles, Ceres is barely one-quarter the Moon’s size. Put it some 210 million miles away, and you can understand why it looks like a dot through a backyard telescope.

But it is a decently bright dot, glowing at magnitude 8.3 as it slides past Beta during March’s first 10 days. So few background stars exist here that Ceres lies in the open. The typical defining characteristic of an asteroid — the night-to-night motion against the stellar backdrop — is a lot tougher to see.

That changes in the following two weeks. The space rock gradually moves in front of a richer star field, and you won’t be able to pick it out at first glance. Still, the pattern of fixed stars gives you a framework to spy the one object that changes place from one night to the next.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.