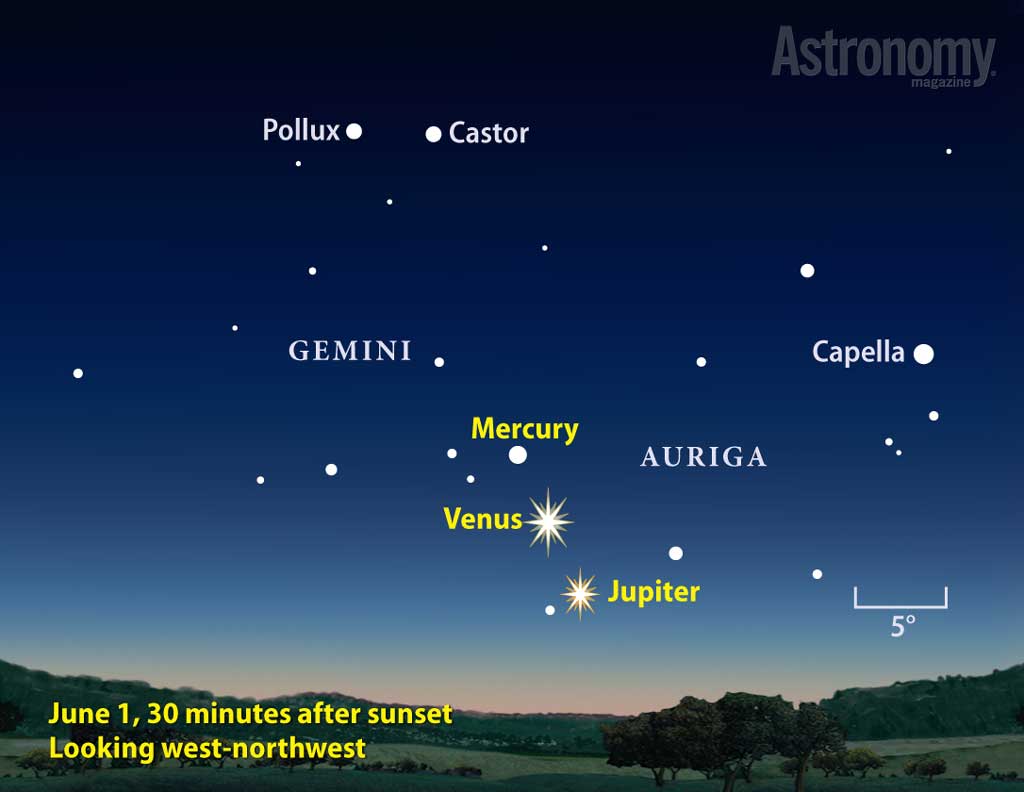

Let’s begin our tour in the western sky shortly after sunset. On June 1, Jupiter, Venus, and Mercury form a straight line angling to the upper left from twilight’s brightest glow. The trio spans just 9°, roughly the width of a closed fist held at arm’s length. Venus shines brightest at magnitude –3.8, followed by Jupiter (magnitude –1.9) and then Mercury (magnitude –0.3). Gemini’s brightest stars, Castor and Pollux, come into view above the planets as twilight fades. The angular separation of the three solar system objects stretches out each evening as Jupiter drops toward the Sun while Venus and Mercury track across Gemini.

Although Jupiter has been a fixture in the evening sky since early winter, its time in the spotlight is nearing an end. The giant planet disappears into the solar glare by June’s second week. It passes on the far side of the Sun on the 19th. Our star actually occults Jupiter that day, an occasion that happens twice during the planet’s 12-year orbit.

Meanwhile, Mercury is heading toward its peak evening altitude for 2013. On June 8, it stands 5° to Venus’ upper left, a degree more separation than on the 1st. Mercury then sets nearly two hours after the Sun, although it has faded to magnitude 0.2. When viewed through a telescope, the planet shows a growing disk with a waning phase. During June’s first week, its size increases from 6.6″ to 7.6″ while its phase dwindles from 60 percent to 45 percent lit.

By the time Mercury slides 2° south of Venus on June 20, the former glows at magnitude 1.2 — 100 times fainter than its neighbor. A wide-field telescope shows both planets together. Mercury appears 10″ across and only 23 percent illuminated. Venus displays a fat gibbous phase on a disk just 1″ wider than Mercury’s.

Venus maintains its brilliance throughout June as it slowly gains altitude. It forms a straight line with Castor and Pollux on June 25, the same day it crosses from Gemini into Cancer.

As dusk settles in during June, Saturn stands nearly halfway to the zenith in the southern sky. It lies in eastern Virgo, where 4th-magnitude Kappa (κ) Virginis will remain its constant summer companion. Saturn lies 1.2° southeast of this star June 1. The gap closes to 0.4° — less than the Full Moon’s width — by month’s end. Saturn fades slightly in June, from magnitude 0.3 to 0.5, as it slowly pulls away from Earth.

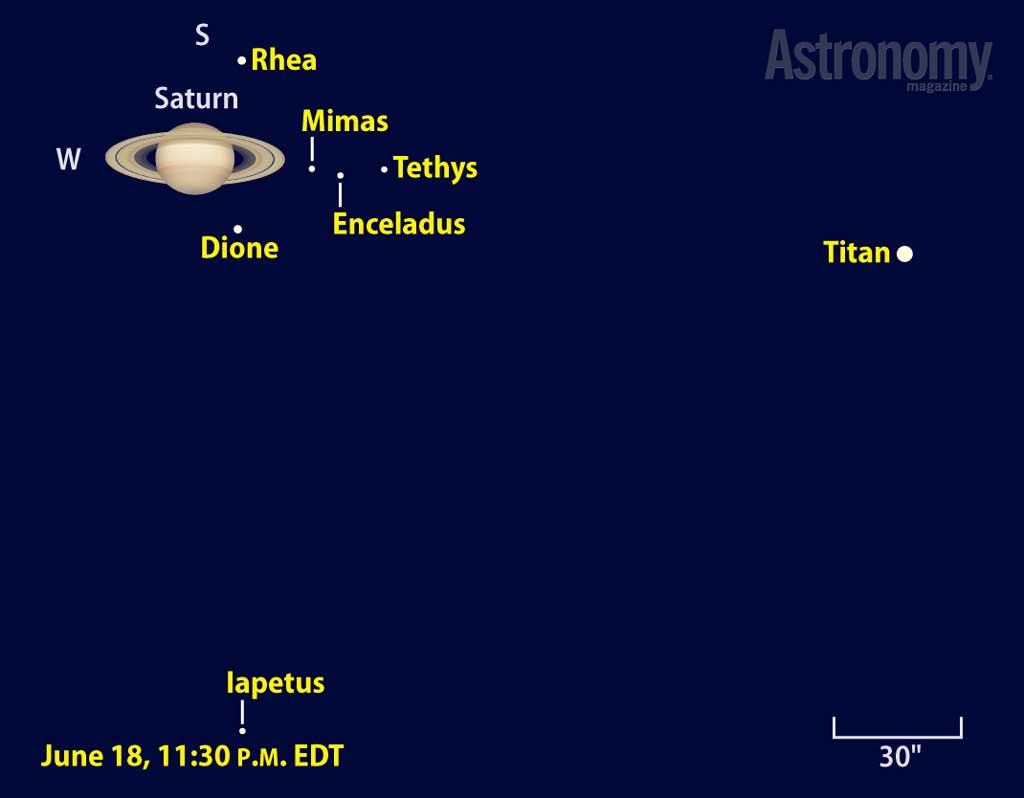

Although the ringed world is great for naked-eye viewing this month, it stands alone among solar system objects for those with telescopes. The magnificent rings are easy to see through any instrument. They span 41″ at midmonth and tilt 17° to our line of sight. They wrap around a disk that measures 18″ across the equator and some 10 percent less through the poles.

Saturn’s outermost major moon, Iapetus, lies 9′ west of the planet June 1, when it shines at 10th magnitude. It dims by a full magnitude by the time it passes 2.5′ north of Saturn on the 18th and 19th. It appears fainter then because its ice-covered hemisphere is rotating out of view. When Iapetus reaches greatest eastern elongation in July, it will glow at 12th magnitude.

Three additional moons shine at 10th magnitude and show up easily through 4-inch scopes, at least when they’re not too near the bright planet. Tethys, Dione, and Rhea circle Saturn on orbits inside Titan’s. They take 1.9, 2.7, and 4.5 days, respectively, to revolve around the ringed world.

You’ll need an 8-inch scope to spy 12th-magnitude Enceladus. Its 1.4-day orbit keeps it within 35″ of Saturn’s center all month, less than twice the radius of the bright rings. You’ll need to increase the aperture another couple of inches if you hope to see Mimas. This tiny moon glows a magnitude fainter than Enceladus and flits around Saturn in just 23 hours, so it always hovers close to the outer edge of Saturn’s rings.

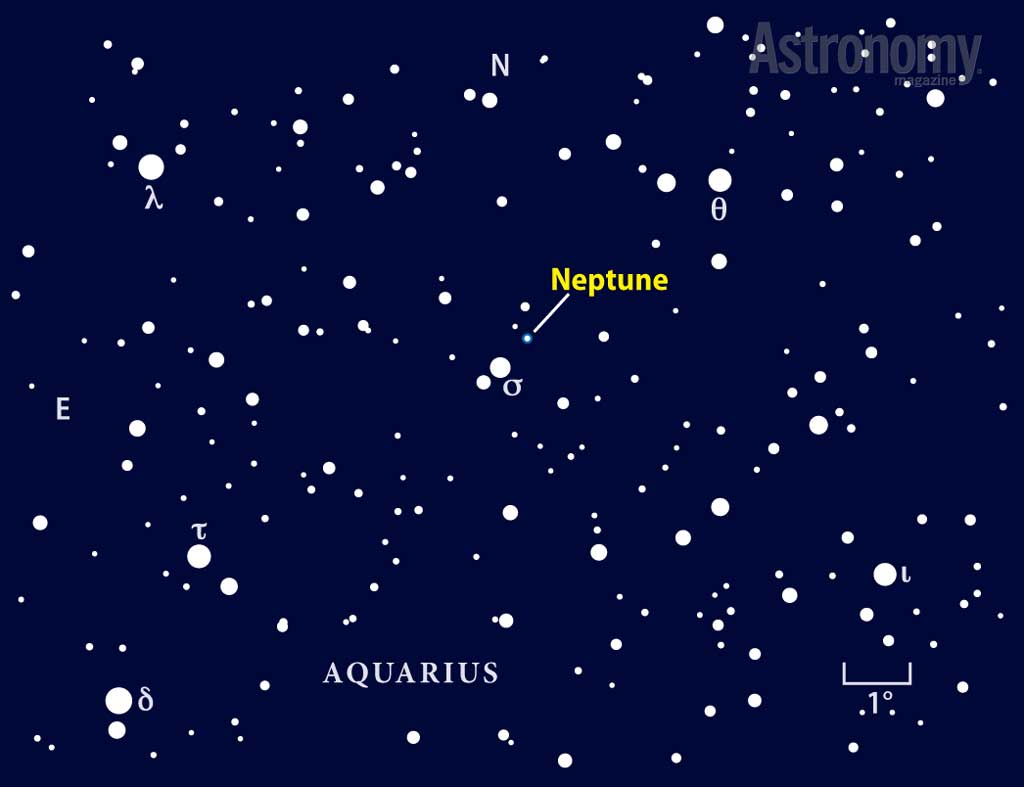

Neptune rises around 1:30 a.m. local daylight time June 1 and some two hours earlier on the 30th. It shows up best shortly before twilight begins, when it lies about 30° high in the southeast. Still, you’ll need some optical aid to spot the magnitude 7.9 planet.

The ice-giant world remains nearly stationary against the relatively barren region of central Aquarius. You can find it 0.6° northwest of 5th-magnitude Sigma (σ) Aquarii. To locate the area, start with four 4th-magnitude stars that form a distorted square: Lambda (λ), Theta (θ), Iota (ι), and Tau (τ) Aqr. Then, draw two imaginary diagonal lines across this figure. Neptune and Sigma lie near the intersection of these lines. When viewed through a telescope, the planet shows a disk that spans 2.3″ and has a noticeable blue-gray hue.

Uranus pokes above the eastern horizon around 3 a.m. local daylight time in early June and stands nearly 15° high as twilight begins. The magnitude 5.9 planet spends the month in Pisces about 4° south of 4th-magnitude Delta (δ) Piscium. A waning crescent Moon lies nearby on the 3rd, occulting the star across much of North America. Uranus shows up through binoculars even with the Moon’s proximity. A telescope reveals Uranus’ 3.5″-diameter disk and blue-green color.

At the end of June, you might catch a brief glimpse of Mars low in morning twilight. The Red Planet rises around 75 minutes before the Sun and climbs just 7° high a half-hour before sunrise. Use binoculars to glimpse the magnitude 1.5 world.

Look near the southwestern limb of a waxing gibbous Moon, and an arresting shoeprint-shaped impact feature will grab your attention. The Sun lights up Schiller on June 19, a few days before Full Moon. The crater’s mostly flat floor and strongly elliptical shape first catch the eye. Although even circular craters appear oval when close to the Moon’s limb, an effect called foreshortening, Schiller seems squashed twice as much as any other in the area.

Until a few decades ago, lunar observers were left scratching their heads trying to explain its form. But research into high-velocity impacts showed that single projectiles hitting at grazing angles can produce some unusual craters, including ones like Schiller. Well after the impact, lava welled up through crustal fractures to form the smooth floor. Messier A in Mare Fecunditatis is the poster child for such low-angle impacts.

To the northeast of Schiller, it’s hard to miss the complex elliptical crater Hainzel. But look closely and you can figure out that separate impacts created it. The northwestern part is a roughly circular feature with a classic central peak. The southeastern section appears to have formed later because its floor better matches the texture and albedo of the overlapping area. Hainzel’s southern component came first. You can tell because the other two overlay it and its rim appears softer from long-term bombardment.

When you’re done here, look at Aristarchus in the Moon’s northern third. When Earth’s atmosphere is turbulent, refraction effects can make this crater appear to be outgassing.

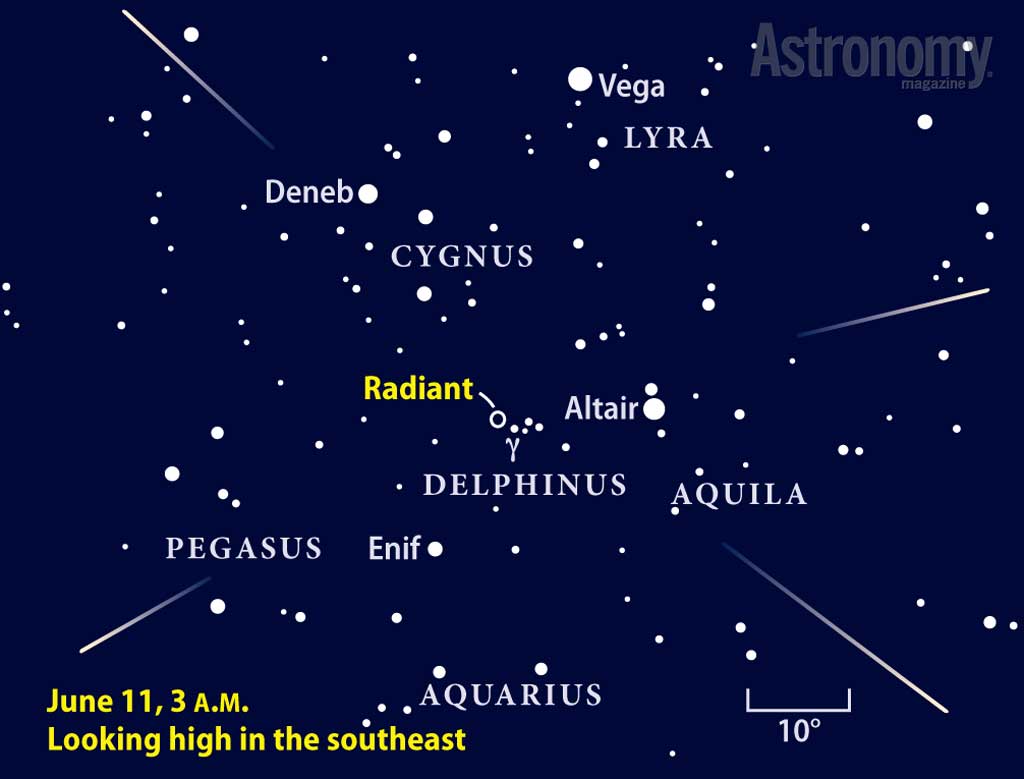

Although June is typically a quiet month for meteors, three experienced observers saw a flurry of activity June 11, 1930. The witnesses recorded meteors from a radiant in the constellation Delphinus, near the 4th-magnitude star Gamma (γ) Delphini.

Despite decades with no reported activity, meteor expert Peter Jenniskens of the SETI Institute predicts 2013 could see a return. His best estimates have a peak occurring June 11 at about 4:30 a.m. EDT. This timing is ideal for early morning viewing from the United States. The radiant then lies high in the sky, and the crescent Moon sets before midnight.

Jenniskens hasn’t made any predictions about the level of activity or how bright the meteors might be, but the one sure thing is that if you don’t watch June 11, you will never know. Astronomers at the International Meteor Organization (www.imo.net) would like to hear from anyone who carefully records their meteor observations that morning.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS |

||

| Evening Sky |

Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Mercury (northwest) |

Saturn (southwest) |

Mars (northeast) |

| Venus (northwest) |

Uranus (east) |

|

| Jupiter (northwest) |

Neptune (southeast) |

|

| Saturn (south) | ||

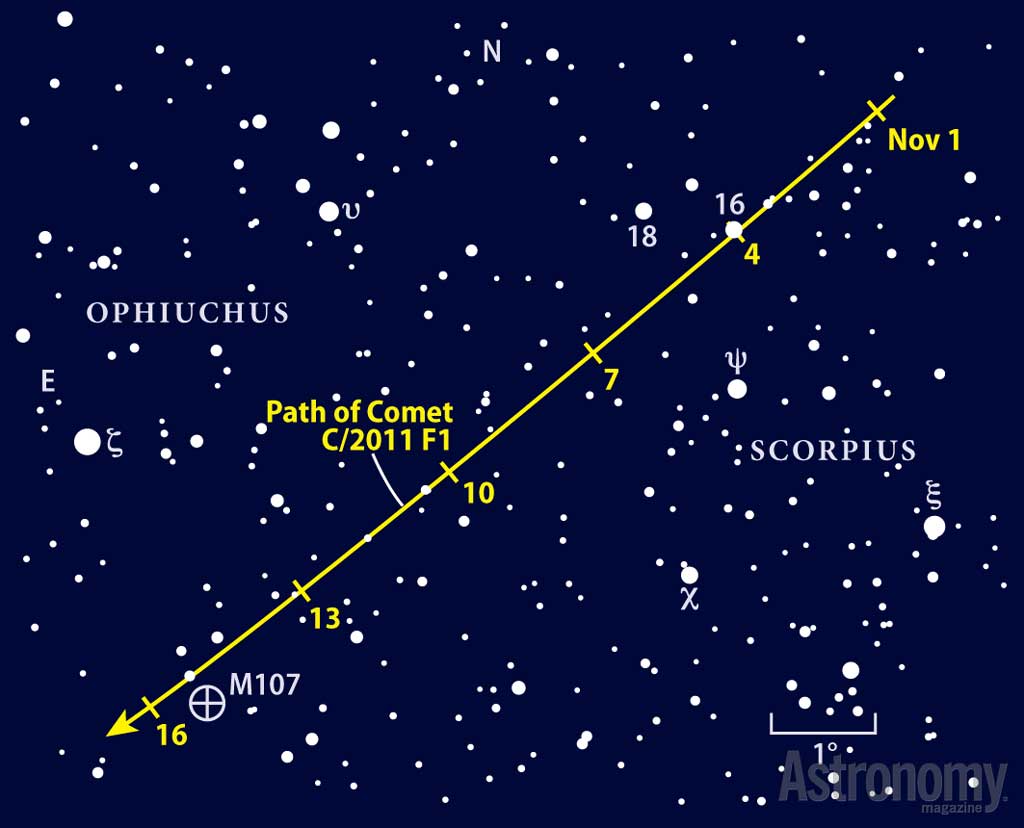

As it recedes from the heat of the Sun toward its home in the frigid Oort Cloud, spring’s lovely Comet C/2011 L4 (PANSTARRS) releases less dust to scatter sunlight back in our direction. Coupled with the comet’s increasing distance from both its light source and Earth, the fuzzy snowball should fade to 9th or 10th magnitude during June.

On the positive side for Northern Hemisphere observers, the comet remains visible all night because it lies near the North Celestial Pole. It slides past Polaris and its cosmic security, the so-called guard stars Kochab and Pherkad (Beta [β] and Gamma [γ] Ursae Minoris, respectively).

The only deep-sky objects in this region are faint galaxies, so you won’t misidentify the grayish cotton ball in 4-inch or larger telescopes. But it will be pretty tough to see PANSTARRS from the suburbs through the veil of light pollution. And because it lies nearly due north, you should scout out a new dark-sky site north of your city and skip the more common ones to the south. Don’t assume that the comet will be easy to bag from June 16 to 19 when it passes within 1° of 2nd-magnitude Kochab. Interference from a waxing gibbous Moon will make that a challenging observation.

To help maximize the contrast between the comet and sky, push the magnification to 120x or more and use a dark hood over your head to keep out stray light and allow your eye to dark adapt as much as possible. PANSTARRS should look somewhat similar to NGC 3077, the satellite galaxy of the bright spiral M81 roughly 20° away in Ursa Major. Both should appear brighter in the middle with diffuse edges, although the sunward-facing edge of the comet should appear sharper.

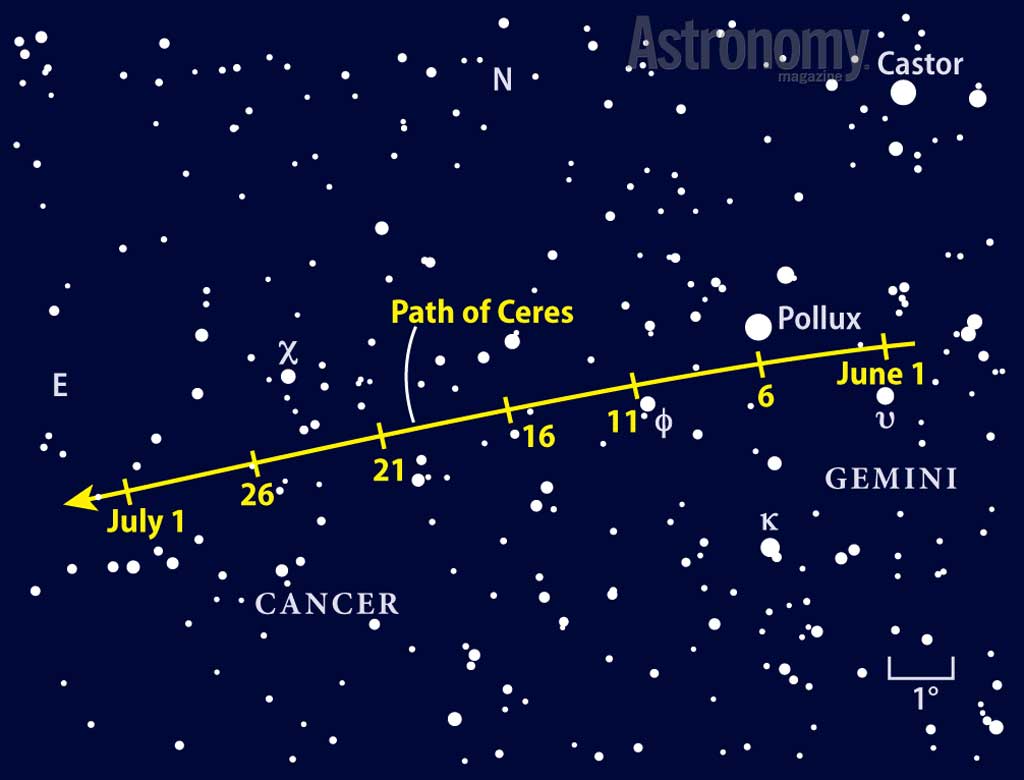

Early June provides a perfect opportunity to star-hop to an asteroid. Just set your scope on 1st-magnitude Pollux and you’re almost on top of Ceres. If you can’t remember which of Gemini’s twins is which, noted astronomy author Ken Hewitt-White suggests this mnemonic: “Castor is closer to Capella, Pollux closer to Procyon.”

Because Ceres sets early, start searching about an hour after sunset. From June 5 to 7, the king of the asteroid belt lies less than 1° south of Pollux. Ceres glows at magnitude 8.8, and only one star in its immediate vicinity appears brighter, at magnitude 8.4. For weekend nights on either side of the asteroid’s close approach to Pollux, star-hopping requires a bit more care and a couple extra minutes.

During June’s second half, 595-mile-wide Ceres crawls across the stardust of Cancer the Crab’s celestial beach. The background stars here appear much the same as the dwarf planet. To make a positive ID, quickly sketch your telescope’s field of view and return a night or two later — the dot that shifted is Ceres. It often can be more satisfying to see the sky change than to take for granted a tick mark on a finder chart.

By June’s close, Ceres dips below the northwestern horizon just before twilight ends. It will pass behind the Sun from our vantage in August and return to the morning sky in late September.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.