The evening sky possesses more subtle attractions. Uranus and Neptune remain binocular targets all month, while Mercury climbs into view during twilight after mid-December. But perhaps the month’s biggest event comes on the 14th when the annual Geminid meteor shower peaks under a Moon-free sky.

Let’s begin our tour of the solar system shortly after the Sun goes down in the latter half of December. Mercury appears above the southwestern horizon starting about 30 minutes after sunset. On the 15th, it lies only 4° high but should show up because it shines so brightly, at magnitude –0.6. (Binoculars will help you to spot it in the twilight glow.)

The innermost planet remains within 0.1 magnitude of this benchmark for the rest of December but becomes significantly easier to see as it climbs away from the horizon. By the time it reaches greatest elongation on the 28th, when it lies 20° east of the Sun, Mercury stands 9° high a half-hour after sundown and doesn’t set until an hour later. When viewed through a telescope in late December, the world shows a disk that measures 7″ across and appears close to half-lit.

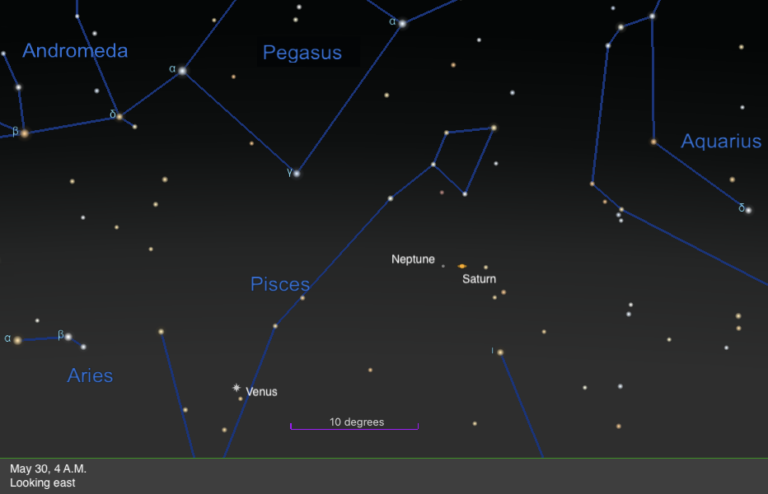

Keep your binoculars handy as the sky darkens, and you can put them to work tracking down the outer two major planets. Neptune lies farther west than Uranus and thus is closer to setting, so target it first. The ice giant planet lies in central Aquarius, a large and relatively inconspicuous constellation that appears nearly halfway from the southern horizon to the zenith as night falls. At midmonth, it sets after 10 p.m. local time.

Neptune glows at magnitude 7.9, nearly 20 times dimmer than Sigma. You may have a hard time seeing this faint with hand-held binoculars. Mount them on a tripod, however, and you can easily view objects a full magnitude fainter. Although binoculars certainly can reveal Neptune, you might not be able to identify it unambiguously. To confirm a sighting, point your telescope at the suspected planet. Neptune will show a disk that measures 2.3″ across and sports a blue-gray color.

Head 40° east of Neptune along the ecliptic — the apparent path of the Sun across the sky that the planets follow closely — and you’ll reach Uranus. This ice giant world, a kissing cousin to Neptune, resides among the faint stars of Pisces the Fish. Uranus appears slightly more than halfway to the zenith in the southeast as darkness falls and remains on view all evening. It doesn’t set until around 1 a.m. local time even as the month comes to a close.

The seventh planet shows up easily through binoculars. Glowing at magnitude 5.8, it is technically visible with naked eyes under a dark sky, though even a little optical aid makes the task much simpler. Uranus moves glacially (appropriate for cold December nights) relative to the background stars in December, remaining 2° due south of magnitude 4.3 Epsilon (ε) Piscium. To quickly find its general location, run an imaginary line diagonally across the Great Square of Pegasus from its northwestern corner (Beta [β] Pegasi) to the southeast (Gamma [γ] Peg) and extend it an equivalent distance.

If you swing your telescope toward Uranus, you’ll see a blue-green disk that spans 3.6″. If you’re observing the slightly gibbous Moon on December 19, slew your scope about 1.5° due north, and Uranus will come into view.

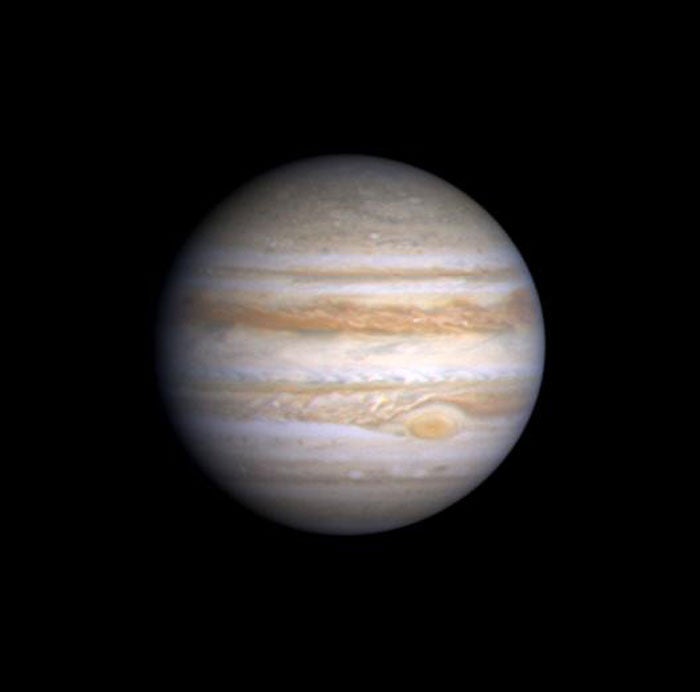

Just as Uranus sets in the west, the eastern sky lights up with the arrival of brilliant Jupiter. The giant planet rises around 12:30 a.m. local time in early December and more than an hour earlier by month’s end. Jupiter brightens from magnitude –2.0 to –2.2 during December against the backdrop of much fainter stars in southeastern Leo.

This large size means you should get exquisite views of jovian cloud features. Most obvious are two relatively dark belts, one on either side of a bright zone that coincides with the planet’s equator. The best views come during moments of steady seeing when the normally turbulent air flowing above your head (and telescope) calms for a few seconds. Take some time now to get familiar with Jupiter and the details visible in its massive atmosphere. This practice will prepare you to see the most when the world reaches opposition and peak visibility in March.

Any telescope also will show Jupiter’s four bright moons. Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto orbit above the planet’s equator and thus wander east and west of the gas giant. When one of them passes in front of Jupiter, you can watch as its dark shadow and then its brighter disk cross the jovian cloud tops.

The angle of the Sun shining on Jupiter diverges noticeably from our line of sight during December. You can get a good idea of the difference December 8. Callisto’s shadow falls on Jupiter’s northern hemisphere starting at 4:17 a.m. EST when the moon itself is still 1.6′ (nearly three Jupiter-widths) east of the planet.

Europa, the target of NASA’s next major planetary mission, casts its shadow on Jupiter’s cloud tops early on the mornings of Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve for observers in the Americas. On both days, Europa’s shadow starts crossing the jovian disk about 2.5 hours before the moon itself.

The planet remains on the far side of the solar system from Earth and thus still looks tiny: a mere 5″ across. At this size, only observers with large scopes can hope to pick up subtle surface details. Mars will grow much bigger, brighter, and more detail-rich next spring as it approaches opposition in late May.

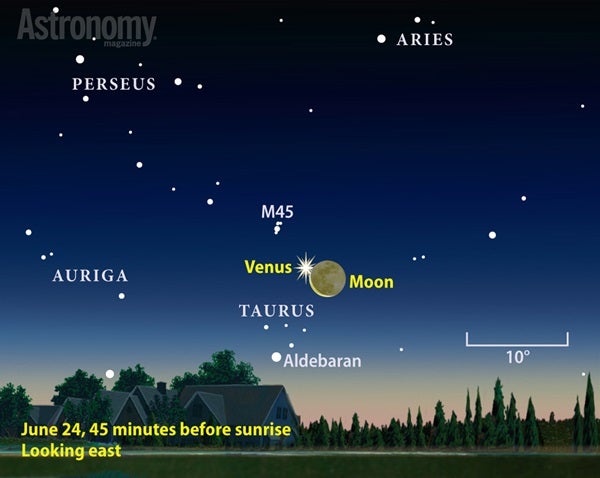

Venus rises about an hour after Mars on December 1 and appears conspicuous in the eastern sky by 4 a.m. local time. At magnitude –4.2, it is five full magnitudes (a factor of 100) brighter than its companion Spica, which stands just 4° away. Venus moves quickly this month, crossing into Libra on the 11th. Look for the magnitude 2.8 double star Zubenelgenubi (Alpha [α] Librae) 2° south of Venus on the 17th.

The rapid changes to Venus’ telescopic appearance this autumn slow considerably in December. The apparent size of its disk shrinks from 17″ to 14″ while its gibbous phase fattens from 67 to 77 percent lit.

If you’re observing the morning of December 7, you’ll no doubt notice the waning crescent Moon closing in on Venus. After sunrise, Luna passes directly in front of (occults) the planet for viewers across North America. You can follow this occultation through binoculars or a telescope.

The time when Venus disappears behind the Moon’s sunlit limb depends on your location. The following are accurate to the nearest minute for several cities across the country: Seattle at 7:54 a.m. PST; Los Angeles at 8:04 a.m. PST; Denver at 9:36 a.m. MST; Houston at 11:12 a.m. CST; Chicago at 11:18 a.m. CST; New York at 12:42 p.m. EST; Boston at 12:43 p.m. EST; and Miami at 12:52 p.m. EST. If you want to view the event through a telescope, be sure to set up at least 30 minutes before these times.

Whether Santa Claus delivers a new telescope or you use just your naked eyes, marvel at the Full Moon high in a late evening sky December 25. Chances are you’ll feel there’s something unusual about it. You’re right. Mare Crisium on the eastern limb looks like it’s nearly on the equator, and if you view through binoculars, the rays pointing back to Tycho reach near the southern limb. Plenty of “extra” light-hued terrain also appears near the north pole.

On the 25th, Luna lies about as far south of the ecliptic — Earth’s orbital plane around the Sun — as it can get. From our earthbound perspective, we see a little past the north pole and down the farside in what astronomers call a northern libration. If you’re up for a little adventure, let’s embark on a trek to the north pole.

Lunar cartographers named many features close to the pole after great polar explorers of past centuries. Two major craters honor the American adventurers Richard Byrd and Robert Peary. Like those pioneers, avoid eyestrain by using sunglasses or a filter to cut down on the Full Moon’s glare. Look just below the northern limb for Byrd, which appears as a large, flat, and fully illuminated oval.

On the 25th, sunlight nicely illuminates this crater’s back wall, which is almost indistinguishable from Peary’s southern flank. The shadows help our minds generate a 3-D view of the polar regions. We can see over and past Peary’s parapets into its partially shadowed floor right up to the back wall. Immediately behind that lies the north pole itself, which remains in shadow.

If you look carefully beyond Peary, you’ll see another lit wall. This is the outer rim of Rozhdestvenskiy, a large crater named for Soviet physicist Dmitriy Rozhdestvenskiy. This feature lies at 87° north latitude on the lunar farside. Off to the east and down the limb a little ways, you’ll find the crater walls of Nansen, named for the Norwegian polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen.

Meteor observers always look at the calendar to see which showers will occur near New Moon. Bright moonlight drowns out fainter meteors and renders the brighter ones less impressive. But no worries this month — the prolific Geminid shower peaks December 14, just three days after New Moon.

The “shooting stars” appear to radiate from a point near Castor in Gemini. The radiant climbs higher in the east throughout the evening and passes nearly overhead around 2 a.m. local time. Don’t stare at the radiant, however — you’ll see longer streaks if you look 40° to 60° away. For the best views, find an observing site far from the city, where you can expect to see up

to 120 meteors per hour.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS |

||

| Evening Sky |

Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Mercury (southwest) |

Jupiter (east) |

Venus (southeast) |

| Uranus (southeast) |

Uranus (west) |

Mars (southeast) |

| Neptune (south) |

Jupiter (south) |

|

| |

Saturn (southeast) |

|

| |

||

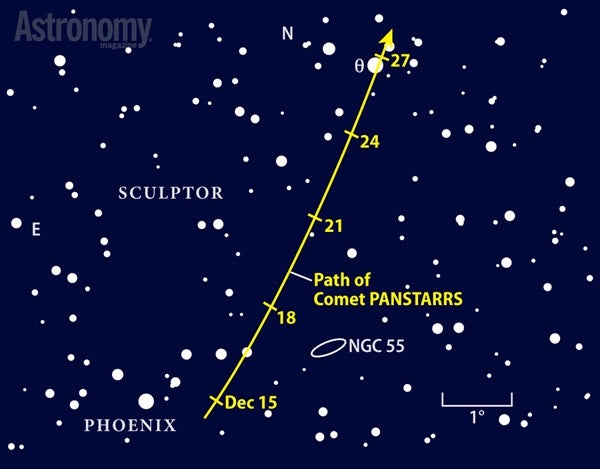

With bated breath, observers across the Northern Hemisphere have been waiting for Comet Catalina (C/2013 US10) to pop into the predawn sky. If all goes according to plan, it could shine as bright as 4th magnitude in early December.

To many people, 4th magnitude hints at naked-eye visibility. Unfortunately, other considerations come into play. First, cities throw up a veil of light that will hide all but the central area. Second, magnitude predictions assume all the light is compressed into a star-like point. In reality, a comet’s glow spreads out into a fuzzy ball and the average surface brightness is lower. Finally, the Moon spills its own light into the sky during early December.

But don’t let that discourage you. The comet should be a pretty sight through binoculars or a telescope at low power. Imagers should be prepared the morning of the 7th to capture Catalina sharing an 8° field with Venus and a thin crescent Moon.

After the 8th, two weeks of Moon-free skies will let observers get detailed views of the comet’s dust and gas tails. From our perspective, the two tails appear distinct. Although the comet’s surface remains hidden by a veil of dust, the surrounding coma may show a greenish hue.

The Moon returns to the morning sky in late December as Catalina sets its sights on brilliant Arcturus. By then, the comet likely will have faded to 5th magnitude.

A small space rock could trigger some excitement among astroimagers when it passes close to the popular galaxy M77. On December 9 and 10, asteroid 39 Laetitia poses as a 10th-magnitude star on the fringe of this bright spiral, mimicking the light from a supernova nearly 50 million light-years away.

M77 is the founding member of Carl Seyfert’s class of active galaxies. Hidden from view by gas, dust, and dense swarms of stars, the galaxy’s core harbors a supermassive black hole busily devouring its surroundings.

You can pick up Laetitia and M77 with a 4-inch telescope from a dark site or an 8-inch instrument from the suburbs. The pair lies less than 1° east-southeast of 4th-magnitude Delta (δ) Ceti. Bump up the power past 100x, let yourself dark adapt a bit, and you should see three other faint fuzzies nearby, all part of the M77 group of galaxies.

To the eye, Laetitia will not move enough to notice during a single viewing session. When it’s near M77 or between Delta and the spiral galaxy NGC 1055, make a quick sketch of the field and return to it the next clear night. The object that has shifted position is the asteroid.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.