Mercury pulls off a rare trick in January. It shows up nicely both after sunset and before sunrise. Our solar system tour begins with the planet’s appearance at dusk during the month’s first week. You can spot Mercury low in the southwest on the first night of 2016 when it stands about 10° high a half-hour after sunset.

The planet shows up well despite the twilight because it shines so brightly, at magnitude –0.4. If you can’t spot it right way, binoculars will gather enough extra light to reveal it. When viewed through a telescope, Mercury appears 7″ across and about half-lit.

The inner world fades rapidly over the next few days. Its telescopic appearance changes just as quickly — on the evening of the 5th, the Sun illuminates just 25 percent of its disk. Mercury soon disappears as it prepares to pass between the Sun and Earth on January 14. It returns to view before dawn late in the month, when we’ll revisit it.

As Mercury dips below the horizon on the 1st, Neptune stands 30° high in the southwest. The outer planet glows at magnitude 7.9 against the backdrop of Aquarius the Water-bearer, some 4° southwest of 4th-magnitude Lambda (λ) Aquarii. You

can spot it through steadily held 7×50 binoculars.

During January’s final two weeks, Neptune lies close to magnitude 6.9 SAO 146230. This star resides a bit more than halfway along a line joining Lambda and 5th-magnitude Sigma (σ) Aqr. The planet lies 13′ due west of the star on the 19th and passes 5′ due north of it on the 26th.

Uranus rides high in the south as darkness falls in January. Although it lies just one constellation east of Neptune, in Pisces the Fish, Uranus remains on view three hours longer than its neighbor. It makes a tempting target for observers using binoculars or a telescope.

Unfortunately, southern Pisces is devoid of bright stars, which makes it a challenge to find Uranus from light-polluted sites. Start with the Great Square of Pegasus, a conspicuous asterism even when viewed from the city. Draw an imaginary line that spans the 20° separating Beta (β) and Gamma (γ) Pegasi (the Square’s northwestern and southeastern corners, respectively), then extend it 15° until you reach a line of three modestly bright stars. With binoculars, focus on the middle and brightest sun: magnitude 4.3 Epsilon (ε) Piscium. Uranus lies 2° south of Epsilon all month.

The magnitude 5.8 planet resides among a small group of 6th-magnitude stars, which complicates identifying the ice giant. The easiest way to confirm a sighting is to point a telescope at your suspected quarry. Only Uranus will show a disk — one with a distinctive blue-green hue that spans 3.5″.

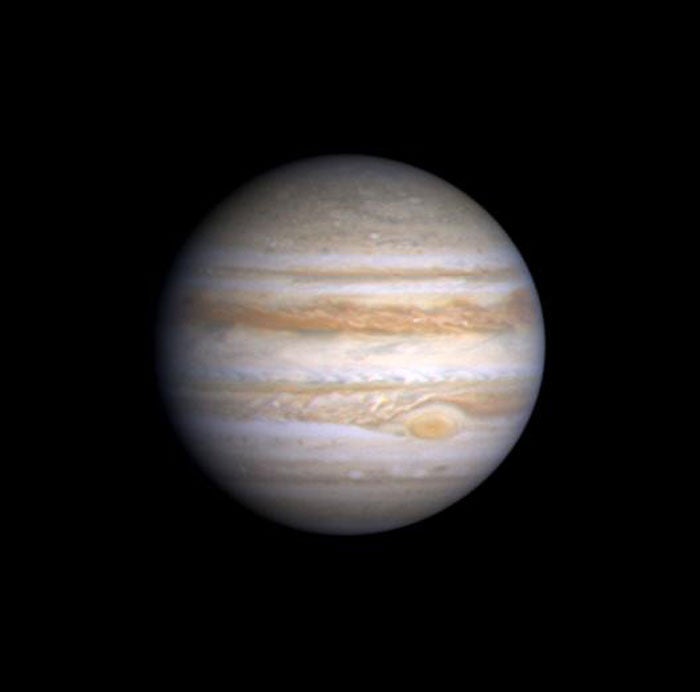

By late evening, you can find Jupiter climbing in the eastern sky. You’ll know that it is about to appear once the figure of Leo the Lion clears the horizon. Jupiter shines at magnitude –2.3, lighting up the rather barren background of southeastern Leo.

For observers eager to sample the planet’s atmospheric wonders, wait until it climbs higher in the sky after midnight. The views won’t disappoint. Jupiter’s equatorial diameter swells from 39″ to 42″ during January, providing a large canvas for seeing cloud-top detail.

Four bright moons — Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto — accompany Jupiter as it orbits the Sun. Small scopes easily reveal their nightly wanderings, which take on added interest when one of them passes in front of (transits) or behind the planet. At least one such event occurs virtually every night.

Perhaps the most intriguing series of events takes place the night of January 10/11 when three moons transit the planet in rapid succession. Europa gets the ball rolling at 11:37 p.m. EST with a transit that lasts until 2:21 a.m. Less than an hour later, at 3:04 a.m., Callisto starts to cross Jupiter’s north polar region. More than halfway through Callisto’s two-hour transit, at 4:22 a.m., Io’s shadow falls on the cloud tops. Io itself begins to transit Jupiter at 5:27 a.m.

The parade of planets picks up once Mars pokes above the horizon in the early morning hours. On January 1, it rises shortly after 1:30 a.m. local time in the company of Virgo the Maiden, 6° east-northeast of that constellation’s luminary, Spica. At magnitude 1.3, Mars appears slightly dimmer than the star, but what really sets them apart are their contrasting colors — the planet has a distinct ruddy hue while the star shines blue-white.

Mars moves eastward relative to the starry backdrop in January, crossing into Libra on the 17th and ending the month 1.3° north of magnitude 2.6 Zubenelgenubi (Alpha [α] Librae). The Red Planet brightens considerably by then, however, shining at magnitude 0.8. Mars’ rapid motion nearly matches the Sun’s pace, so the world rises only about a half-hour earlier at January’s close than it did on New Year’s Day.

Mars was a telescopic dud during 2015 because its diameter never exceeded 5.5″. That starts to change in January because the planet pulls significantly closer to Earth. By month’s end, it appears 6.8″ across and may start to show some subtle surface markings through larger scopes. Conditions will improve quickly this spring as Mars approaches opposition in May, when it will appear bigger and brighter than at any time since 2005.

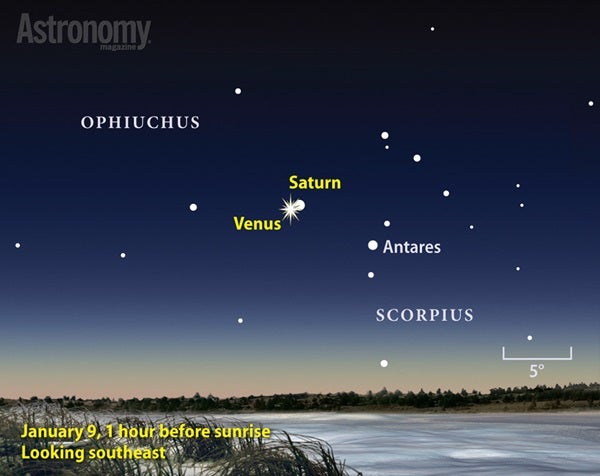

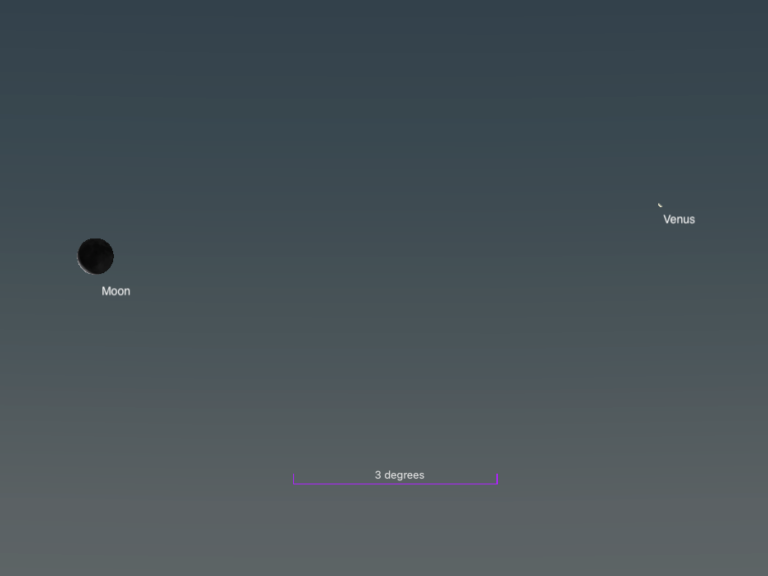

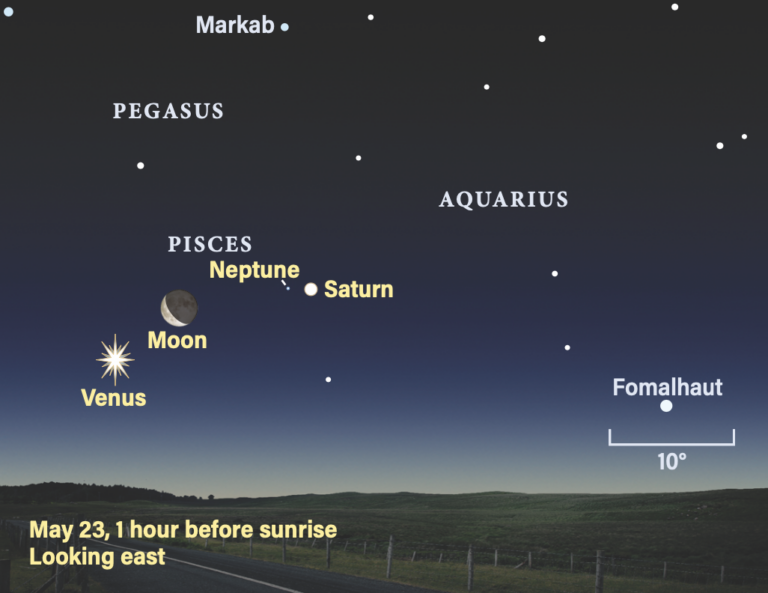

The gap between the two worlds closes rapidly, however. Venus skips across the narrow northern section of Scorpius in just four days, entering Ophiuchus on January 5. A pretty scene occurs the following morning when a waning crescent Moon joins the planets before dawn. Look for the Moon 7° above Venus with Saturn standing 3° below its sister world.

Three mornings later, on January 9, Venus and Saturn make their closest approach in a decade. Western Europeans have the best view, with the two planets passing just 5′ apart at 4h UT. By the time the pair rises in eastern North America, 17′ separate the two, and the gap grows to 25′ on the West Coast. Still, both objects will appear in a single field of view through a telescope at low power. Venus shows a 14″-diameter disk that is 80 percent illuminated while Saturn appears 15″ across with a ring system that spans 35″.

Mercury approaches Venus at the tail end of January. The innermost planet stands 9° high in the southeast a half-hour before sunrise on the 31st, when you can locate it 7° to Venus’ lower left. It shines at magnitude 0.0 and should show up clearly through binoculars. Of academic interest only, Mercury passes 0.5° north of Pluto (invisible in twilight, of course) on the 30th.

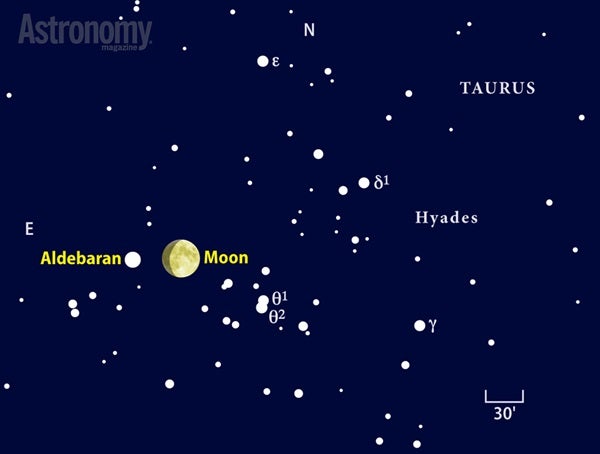

Although no planet calls Taurus home this month, the constellation does host a spectacular solar system event. On the evening of January 19, the Moon occults Aldebaran, the Bull’s brightest star, for observers north of a line that runs across northern Mexico and the U.S. Gulf Coast. The unlit edge of the waxing gibbous Moon overtakes Aldebaran in twilight along the West Coast but after darkness everywhere else. Be sure to set up ahead of time, center the star in your telescope’s field of view, and watch the magnificent show.

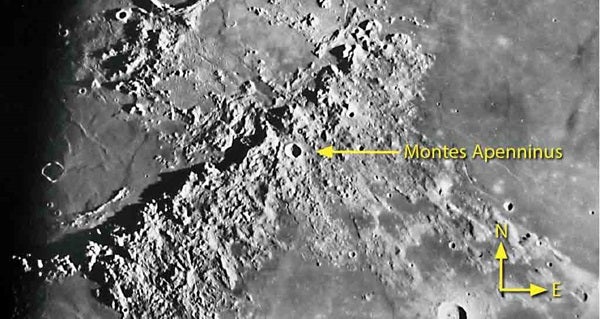

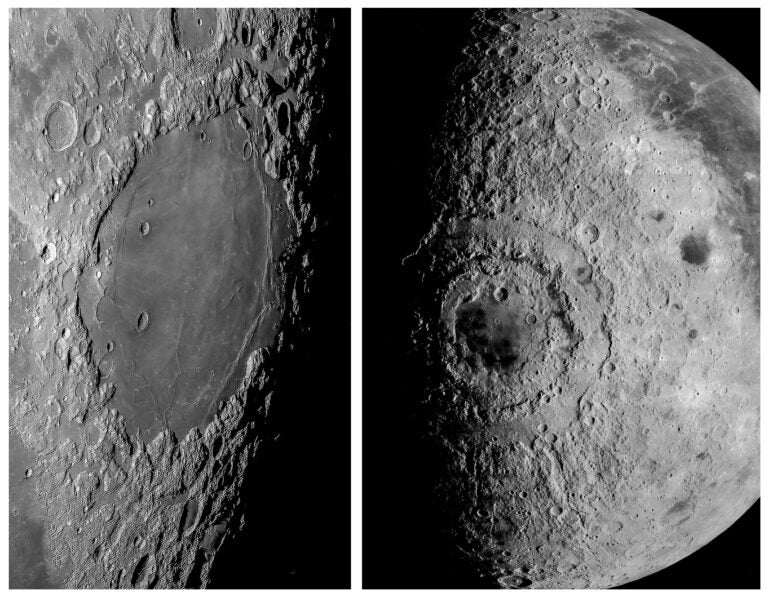

A half-lit Luna is a detail-packed world of dramatic contrasts. If you observe the First Quarter Moon on January 16, you’ll find a grand mountain range straddling the middle of the disk just north of the equator. Montes Apenninus (Apennine Mountains) are rugged compared with the smooth lava plains to their east. The long shadows at sunrise tell us the peaks thrust upward some 3 miles. Identify a black saw-tooth shape reaching for the nightside, then return to it every 10 minutes or so and see it grow shorter.

The spine of the Apennines curves gently to the northeast, eventually turning into Montes Caucasus (Caucasus Mountains). They also continue southwest into darkness, a region that becomes fully visible on the 17th.

Three decades after Galileo’s first observations of the Moon, lunar cartographer Johannes Hevelius published a map using names inspired by European geography. The earthly Apennines form the backbone of Italy. Of the nearly 300 lunar features Hevelius labeled, however, only 10 remain today, and they are all mountains and ranges.

A century ago, observers would have been stunned to learn that the lunar Apennines are but a small section of a vast bowl some 710 miles across that formed when a hefty asteroid slammed into the young Moon. Millions of years later, the Imbrium Basin filled with lava bubbling up from the molten interior. Look closely along the shoreline and you’ll see partially filled craters and blocks of rock collapsed away from the wall. Also look for wrinkle ridges — features that formed as the lava cooled and contracted — on the smoother plains that show up at low Sun angles.

SHOOTING STARS WELCOME THE NEW YEAR

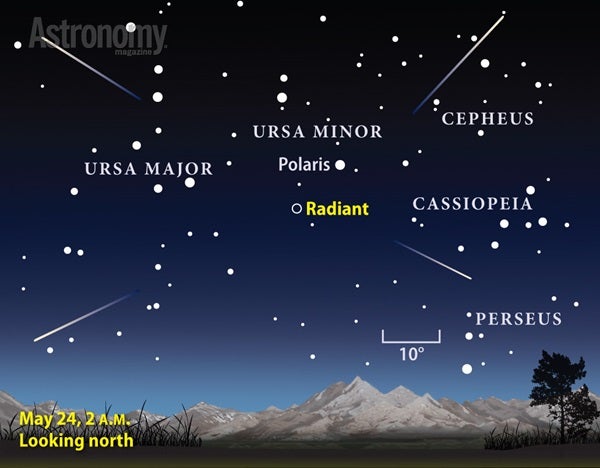

This year’s meteor calendar starts off with a bang. The Quadrantid meteor shower peaks before dawn January 4, and though a waning crescent Moon shares the sky with this prolific shower, its minimal light won’t have much effect. Observers under an otherwise dark sky can expect to see up to 120 meteors per hour shortly before morning twilight commences.

Quadrantid meteors appear to radiate from a point in the constellation Boötes. Yet the shower doesn’t take the name of its host constellation like most others do. In the 19th century, when astronomers first described this shower, the radiant resided in the now-defunct constellation Quadrans Muralis. The name stuck, and the only Boötid meteors now come during a relatively minor shower that peaks in late June.

The Quadrantid radiant lies in northern Boötes, below the Big Dipper’s handle in January’s morning sky. The area climbs high in the northeast during the predawn hours on the 4th.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS |

||

| Evening Sky |

Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Mercury (southwest) |

Jupiter (east) |

Mercury (southeast) |

| Uranus (south) |

Venus (southeast) |

|

| Neptune (southwest) |

Mars (south) |

|

| |

Jupiter (southwest) |

|

| Saturn (southeast) |

||

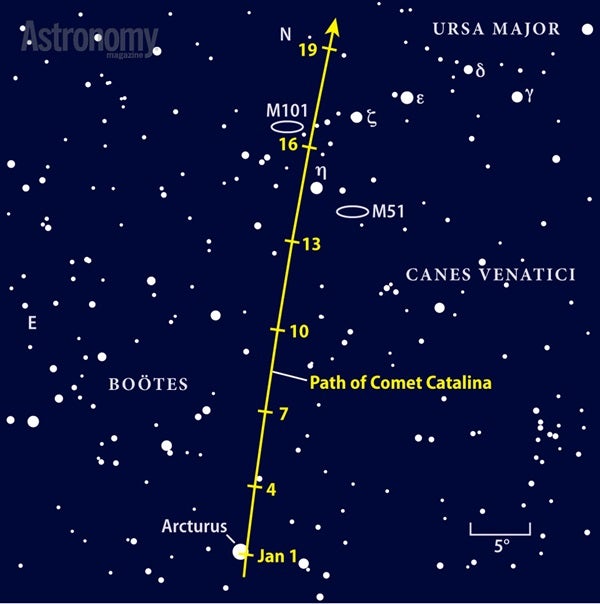

With almost perfect timing, Comet Catalina (C/2013 US10) crests the eastern horizon just after the ball drops on New Year’s Eve. But can you see the 5th-magnitude comet in the glare of magnitude 0.0 Arcturus? Catalina passes within 0.5° of the star in the predawn hours of January 1. It doesn’t hang around for long, however — this dirty snowball cruises northward at better than 2° per day.

The waning Moon exits the morning sky on the 7th, by which time Catalina rises before midnight. Still, your best views will come when the comet rides high in the sky before dawn. Pay particular attention from January 14–17, when this visitor from the distant Oort Cloud passes near the Whirlpool Galaxy (M51) and M101, a pair of photogenic spiral galaxies. Wide-angle images should capture the scene beautifully. Chance grants us these vistas shortly before the waxing gibbous Moon puts an end to this month’s dark-sky window.

When viewed through a telescope, a 5th-magnitude comet typically sports a fair bit of detail. Use low power and sweep along the length of the tail, which should allow you to trace the comet’s ejecta for several degrees. The tail’s northern flank will be sharp because this is the border between the comet’s ionized gas and the relative emptiness of interplanetary space. The southern flank appears softer because the dust thins out more gradually.

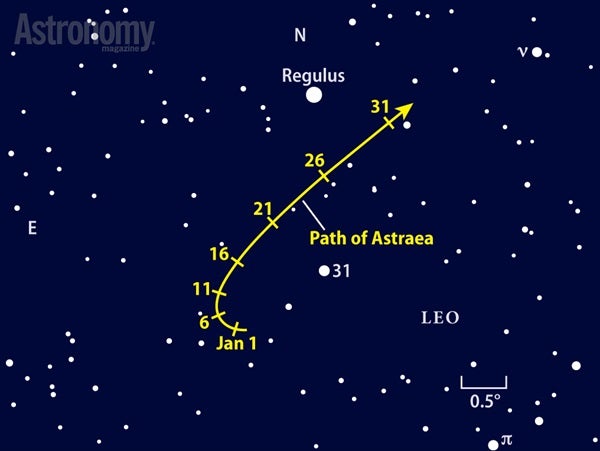

Leo the Lion rides high in the east in the late evening sky and peaks in the south after midnight. The constellation’s brightest star is 1st-magnitude Regulus, a name that translates as “little king.” (You’ll also see it called Cor Leonis [“heart of the lion”] in reference to its position in Leo.)

This blue-white luminary serves as the starting point for locating asteroid 5 Astraea. The minor planet passes 1° due south of the star January 25 but pulls even closer (0.75° away) a few days later. Astraea glows at 9th magnitude and should be easy to pick out from the starry backdrop near Regulus.

Use the chart below to home in on the asteroid earlier in the month. Fourth-magnitude 31 Leonis serves as a nice secondary anchor. None of the background stars near Astraea’s path are as bright as the asteroid, so identifying it should be a snap.

German astronomer Karl Hencke discovered Astraea in December 1845. In the nearly 40 years after Vesta’s 1807 discovery, most astronomers were convinced that just four objects existed between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, and many considered them planets. Astraea’s discovery triggered their downfall from planethood and ushered in the age of asteroids.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.