But there is plenty more on tap during these pleasant spring nights. Jupiter will captivate anyone who looks up during the early evening hours, while beautiful Saturn entices viewers to stay up past midnight. It’s a month of superlatives and contrasts sure to thrill any planetary observer.

As twilight fades in early May, Jupiter rides about 60° above the southern horizon. It gleams at magnitude –2.3, far outshining the background stars of southern Leo the Lion. In fact, no other planet or star beats this giant world. Jupiter slowly pulls away from Earth during May, however, and by month’s end, it has dimmed by 0.2 magnitude.

The planet’s increasing distance will catch your eye if you view it through a telescope. Jupiter’s apparent diameter shrinks nearly 10 percent during May, dropping from 41″ to 37″. Fortunately, that’s still plenty big enough to reveal delicate shadings in Jupiter’s cloud tops. Pay particular attention to the two dark belts that straddle a bright zone coinciding with the planet’s equator. Under steady seeing conditions, a series of alternating belts and zones extend to higher latitudes. Don’t be afraid to observe the gas giant during twilight — this technique cuts down on glare and provides unexpectedly pleasing views.

Four bright moons accompany Jupiter as it circles the Sun. Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto change positions constantly relative to one another as they orbit the giant planet. Even a small scope lets you track their behavior. The most exciting views come when a moon passes directly in front of Jupiter (a transit) and shortly thereafter casts its shadow onto the jovian cloud tops (a shadow transit).

Although dozens of such events occur during May, only four involve outermost Callisto. And of those, only one occurs when Jupiter is visible across North America. On the night of May 6/7, the moon’s shadow looks like a black dot as it treks across the planet’s north polar region from 11:18 p.m. to 1:42 a.m. EDT. Don’t confuse Callisto’s shadow with that of Io, which begins its own transit much closer to Jupiter’s equator at 12:39 a.m. EDT.

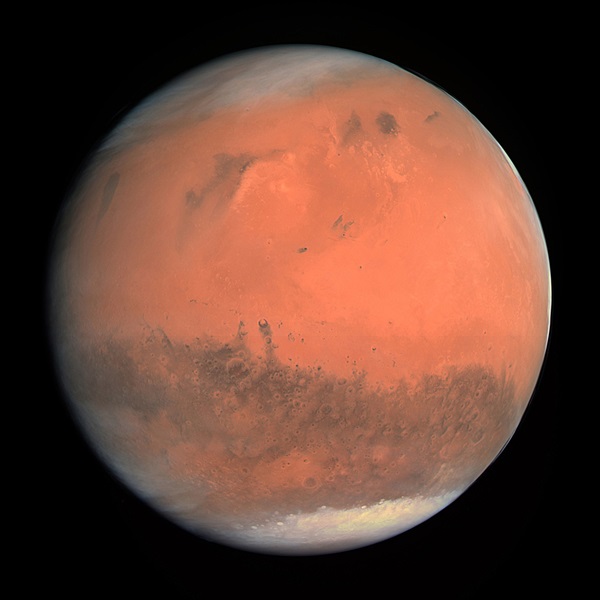

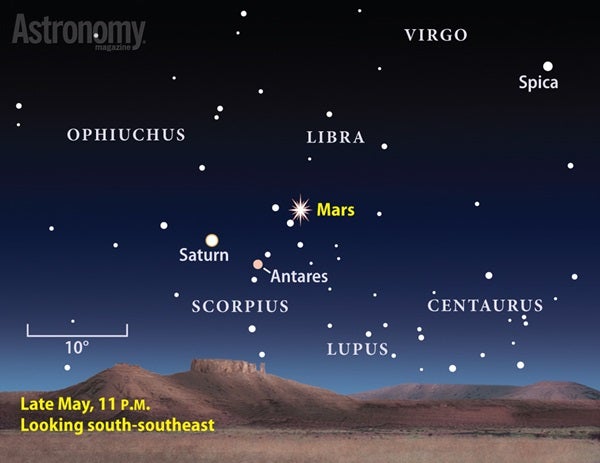

Mars reaches opposition and peak visibility during the latter half of May, but it remains an impressive sight all month. On the 1st, it rises around 10 p.m. local daylight time along with the background stars of northern Scorpius the Scorpion. Shining at magnitude –1.5, the Red Planet far surpasses every other celestial object in this part of the sky.

Two other prominent objects join Mars within the next hour. The planet’s ancient rival, 1st-magnitude Antares in Scorpius, and magnitude 0.2 Saturn poke above the southeastern horizon nearly simultaneously a half-hour after Mars. The Red Planet lies 5° north-northwest of Antares and 8° west of Saturn. The two planets dramatically alter the Scorpion’s appearance this month.

Mars treks westward relative to the starry backdrop in May. It slides 1.2° north of the 7th-magnitude globular star cluster M80 on the 6th and 1.0° north of the 2nd-magnitude double star Delta (δ) Scorpii on the 19th.

On May 22, Mars lies opposite the Sun in our sky, so it rises near sunset and remains visible all night. The planet also appears most dazzling around opposition, peaking at magnitude –2.1. That’s about 70 percent more luminous than it was just three weeks earlier and the brightest it has been since 2005.

But in at least one aspect, the best is yet to come. On May 30, just two days after Mars’ westward motion has carried it across the border into Libra the Scales, the Red Planet comes closest to Earth. The centers of our two planets then lie just 46.8 million miles apart. The minimal separation means Mars looms large through a telescope, peaking at a diameter of 18.6″.

Although Mars will garner the lion’s share of attention from observers this month, don’t shortchange Saturn. The ringed planet will reach opposition in the first few days of June, and the view during May is hardly less impressive. Saturn brightens from magnitude 0.2 to 0.0 this month, making it second only to Mars in this part of the sky. And its yellow glow contrasts nicely with the ruddy hues of its neighbors, Mars and Antares. The ringed planet spends the entire month edging westward across the feet of Ophiuchus the Serpent-bearer.

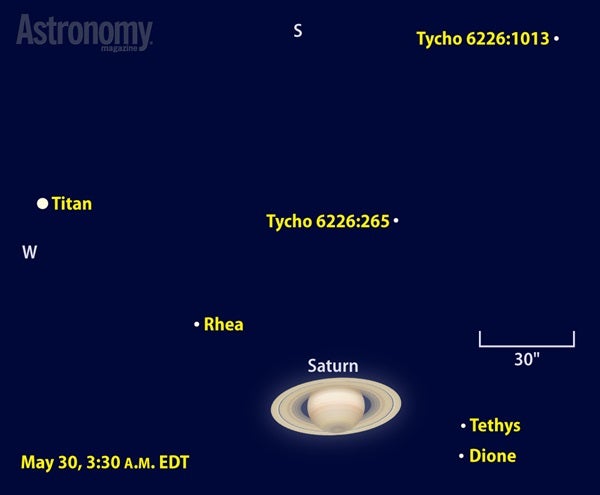

Saturn’s disk measures 18.3″ across the equator in mid-May, just 0.1″ short of its opposition diameter. Look carefully through a telescope and you may see at least one slightly darker belt in the planet’s atmosphere. Also notice that the area surrounding the north pole appears darker than the equatorial region.

Of course, the rings are what give Saturn its majesty. They span 41.6″ at midmonth and tip 26° to our line of sight. The large tilt affords observers exquisite views of the ring system through even the smallest scopes. Note in particular the dark Cassini Division that separates the outer A ring from the brighter B ring.

Small scopes also reveal Saturn’s largest moon, 8th-magnitude Titan. It passes due north of Saturn the mornings of May 5 and 21 and due south May 13 and 29. Between these dates, it can reach up to 3′ east or west of the planet.

Not surprisingly, Saturn’s smaller moons glow more dimly. Tethys, Dione, and Rhea all shine at 10th magnitude and will show up through 4-inch instruments. They orbit closer to the planet than Titan and appear no more than 1′ from the edge of the rings. Don’t mistake these moons for two 10th-magnitude field stars that appear in the same general area the night of May 29/30.

Mercury passes directly between the Sun and Earth on May 9 for the first time since November 8, 2006. Observers across most of the globe (excluding Australia, New Zealand, eastern Asia, and the surrounding oceans) can witness some or all of this 7.5-hour transit. You’ll need a telescope equipped with a safe, full-aperture solar filter to see the planet’s 12″-diameter black disk against the Sun’s surface. For specifics on observing this exceptional event, see “How to view Mercury’s rare transit” on p. 62.

Following the transit, Mercury moves into the morning sky. By late May, the innermost planet has climbed into view low in the east before dawn. On the 31st, it lies 23° west of the Sun but stands just 4° high a half-hour before sunrise. Shining at magnitude 0.9, Mercury will be hard to see so low in the twilight glow. Better views await observers in early June when the planet brightens and climbs higher.

Joining Mercury before dawn is the outermost major planet, Neptune. You’ll need binoculars or a telescope to spot this 8th-magnitude world against the backdrop of Aquarius the Water-bearer. It remains within 0.5° — the diameter of a Full Moon — of 4th-magnitude Lambda (λ) Aquarii all month, appearing due south of the star during May’s first week. On the 2nd, a waning crescent Moon passes less than 1° north of Neptune with Lambda residing between the two.

Uranus remains too close to the Sun this month to see easily from mid-northern latitudes. Twilight interferes until May’s final week, and even then, the 6th-magnitude planet appears only a few degrees above the eastern horizon.

It and its host constellation, Pisces the Fish, will come into better view next month.

Venus now lies on the far side of the Sun from Earth and is hopelessly lost in our star’s glare. It will return to view after sunset in July.

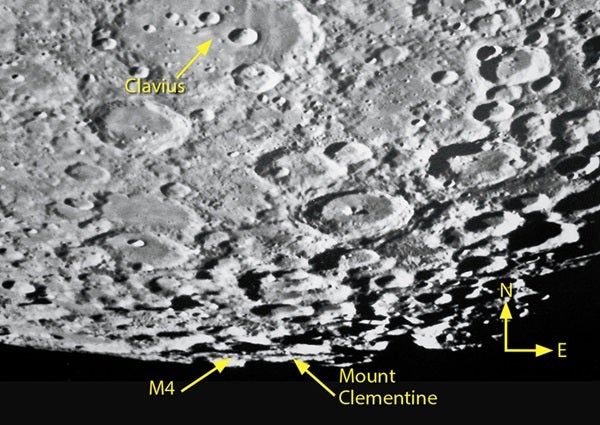

Where’s the best place on the Moon to build a solar-powered station? It’s on a hill on the lunar farside just “beyond” the south pole that suffers only a brief interruption from continuous sunlight. M5, unofficially known as Mount Clementine, undergoes a short eclipse as the shifting shadow of its neighbor M4 swings across it once a month. Most lunar locales endure total darkness for nearly 15 days.

Without a doubt, Mount Clementine is the easiest farside feature to see — if the timing is right. When the Moon climbs well north of Earth’s orbital plane (the ecliptic), we can peer a bit “under” its south pole. The timing this month coincides with Full Moon on May 21, delivering near-perfect views with an outstanding 3-D perspective. The extra viewing angle shows us the shadow cast by every hill.

Elsewhere on the Moon, a rising Sun casts a mountain’s shadow to the west. But near the south pole, shadows gradually swing around in a circle. The modestly tall bump in front of Clementine first casts its shadow to the base of M4. It marches eastward on following nights, crossing the base of Clementine. A few nights later, M4 itself puts Clementine in darkness.

Be patient and wait for good seeing. The glare of a Full Moon can be nearly unbearable at low power in larger instruments. If this happens to you, step up the magnification or use a dark blue or green filter to cut down the light.

Comet 1P/Halley passes through the inner solar system every 75 years. And though it is not scheduled to come back until 2061, you can spy pieces of this famous visitor in early May. That’s when Earth plows through debris Halley left behind on previous visits, giving us the Eta Aquariid meteor shower.

The shower peaks in North America the afternoon of May 5, so equally good views should come before dawn on the 5th and 6th. This coincides with New Moon — the only major meteor shower that can make this boast in 2016. From a dark site, you should notice 10 to 20 meteors per hour emanating from Aquarius. Observers in the Southern Hemisphere, where Aquarius passes nearly overhead, typically see the most meteors.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS |

||

| Evening Sky |

Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Mars (southeast) | Mars (southeast) | Mercury (east) |

| Jupiter (south) | Jupiter (west) | Mars (southwest) |

| Saturn (southeast) | Saturn (southwest) | |

| Uranus (east) | ||

| Neptune (southeast) | ||

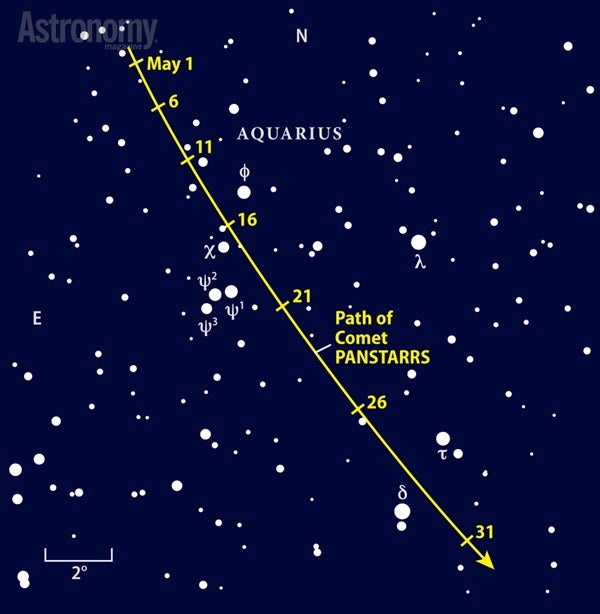

Observers across the contiguous United States and points south should have a nice 7th-magnitude comet to view through their telescopes on May mornings. The catch: Comet PANSTARRS (C/2013 X1) struggles to climb above the horizon haze before dawn breaks. You’ll need a clear, flat eastern horizon to spot PANSTARRS as it slides south through Aquarius.

A plethora of comet possibilities lurk in the evening sky, but barring a surprise newcomer, none glows brighter than 11th magnitude. The best of the lot is Comet 9P/Tempel, which lies in Leo the Lion’s hindquarters, not far from 2nd-magnitude Denebola. You should be able to view this periodic visitor through a 6-inch scope under a dark sky. Use the finder chart for asteroid Hebe on the opposite page to zero in on 9P/Tempel.

The comet should appear as a small, slightly flattened V shape with a condensed center. On the evening of May 6, compare it with the 12th-magnitude spiral galaxy NGC 3801. The two objects appear just 10′ apart.

Comet 9P/Tempel’s name might ring a bell. Eleven years (two revolutions) ago, NASA’s Deep Impact mission blasted the comet with a large cube of copper and measured the effects. The comet will approach Jupiter in 2024 and get nudged into a slightly larger orbit, making it a fainter object at subsequent returns.

The eccentric orbits of the minor planets provide Earth-bound observers with an unending parade. As luck would have it, the year’s biggest floats won’t arrive until fall, leaving the smaller and fainter ones for this spring. Yet asteroid 6 Hebe is not hard to find. A 3-inch telescope under country skies or a 5-inch instrument from the suburbs will let you track its motion near 2nd-magnitude Denebola in Leo the Lion’s tail.

At the start of the month, a fuzzy 11th-magnitude comet shares the same field of view. Hebe lies more than twice as far away as Comet 9P/Tempel, however, so it moves little from one night to the next. That’s good news for those who like to sketch an asteroid’s motion relative to the background stars — Hebe takes more than a week to cross one field of view.

German amateur astronomer Karl Hencke discovered this main belt object in July 1847. He found it by systematically comparing the views through his telescope with those on the best star charts of the time, looking for any object that didn’t belong. German mathematician Karl Friedrich Gauss proposed naming it Hebe after the Greek goddess of youth.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.