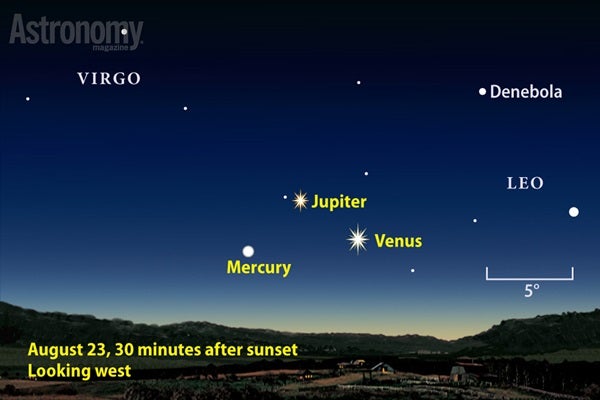

Our tour of Earth’s night sky begins in early evening twilight. As August opens, Mercury, Venus, and Jupiter form a straight line. Venus lies closest to the horizon while Mercury appears to its upper left and Jupiter stands highest. Venus shines brilliantly at magnitude –3.8 and should show up nicely without optical aid a half-hour after sunset. Jupiter glows more dimly, at magnitude –1.7, but its greater altitude makes it an easy target. You’ll likely need binoculars to spot magnitude –0.1 Mercury 8° to Venus’ upper left.

A crescent Moon passes this trio during August’s first week. On the 3rd, you’ll need a haze-free sky and an uncluttered horizon to spot a one-day-old Luna 3° below Venus. At mid-northern latitudes, the Moon sets only 30 minutes after the Sun; conditions improve the farther south you live. You have a better chance of seeing our satellite on the 4th, when it stands 2° to Mercury’s left and both objects lie 6° high 30 minutes after sunset. On the following evening, a slightly fatter crescent appears 1° below Jupiter.

Venus spends the month climbing away from the Sun while Jupiter sinks closer to our star — a recipe for their late-August rendezvous. Mercury does a bit of both. The innermost planet moves farther from the Sun until it reaches greatest elongation

on August 16. It then lies 27° east of the Sun and appears 4° below Jupiter. Although Mercury has faded to magnitude 0.2, it remains relatively easy to see against the twilight.

Mercury then starts to head back toward the Sun while Venus and Jupiter, which lie 11° apart on the 16th, continue to close in on each other. The three planets form an elegant triangle that changes shape each evening. Perhaps the prettiest scene occurs on August 23, when Jupiter stands 4° from both Mercury and Venus and the two inner planets appear 6° apart.

Binoculars will provide stunning views of the vista, clearly splitting the pair while also revealing Mercury 5° to their lower left and just above the horizon. Most telescope-eyepiece combinations will show Venus and Jupiter in the same field of view. Jupiter appears 31″ across, nearly three times bigger than Venus’ 11″ diameter. Neither object will show much detail because their light must pass through large amounts of Earth’s image-distorting atmosphere. (To see features in Jupiter’s cloud tops, look early in the month when it lies significantly higher.)

Following their magnificent conjunction, the two brightest planets separate. On August’s final evening, Venus appears 4° to Jupiter’s upper left. Mercury has faded considerably and is lost in the Sun’s glare.

As twilight deepens and the planets in the west dip below the horizon, shift your attention to the south. Another pair of bright planets — Mars and Saturn — rules this domain. Mars shines at magnitude –0.8 on August 1 when it sits on the border between Libra and Scorpius. It then resides 10° west-northwest of Antares, the 1st-magnitude luminary of Scorpius whose ruddy color closely resembles that of the Red Planet. Saturn provides a nice color contrast, glowing with a hint of yellow at magnitude 0.3. It lies 6° north of Antares on the 1st. On August 11, a slightly gibbous Moon stands 8° north of Mars and 7° northwest of Saturn.

Mars wanders eastward during August, crossing Scorpius in three weeks and entering Ophiuchus on the 21st. Two nights later, it passes 2° north of Antares and appears in line with the star and Saturn. Mars passes 4° due south of the ringed planet on the 25th. While Mars moves quite rapidly relative to the background stars this month, Saturn remains nearly stationary in the southwestern corner of Ophiuchus.

Although Mars reached its peak in late May, it remains a worthy target for telescope owners. Its disk spans 13″ on August 1 and shrinks to 11″ across on the 31st — plenty big enough to show subtle surface markings. Just be sure to view before 10 p.m. local daylight time, when it lies above 15° altitude and atmospheric conditions don’t interfere too much.

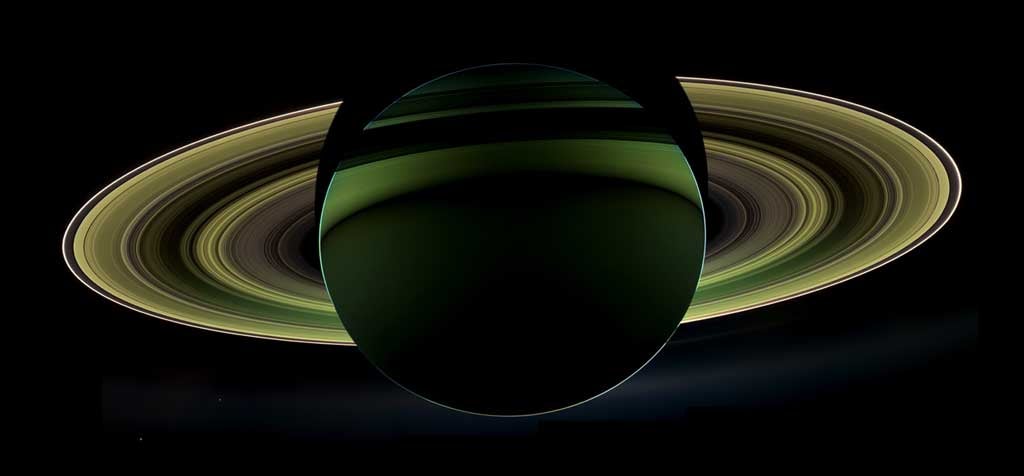

First, savor the overall view, then look more closely for fine details. You should notice that the planet looks flattened — its equatorial diameter is nearly 10 percent bigger than its polar diameter. (In mid-August, those values are 17.2″ and 15.8″, respectively.) The flattening arises because Saturn is made of gas and spins rapidly.

Next, examine the ring system. It spans 39″ at midmonth and tips 26° to our line of sight. The wide tilt allows structure to stand out. Notice the dark Cassini Division that separates the outer A ring from the brighter B ring. The faint, innermost C ring appears as a slight darkening where it passes in front of the planet. Typically, it shows up only under the best observing conditions. Finally, look for Saturn’s shadow falling on the backside of the rings just east of the planet’s limb.

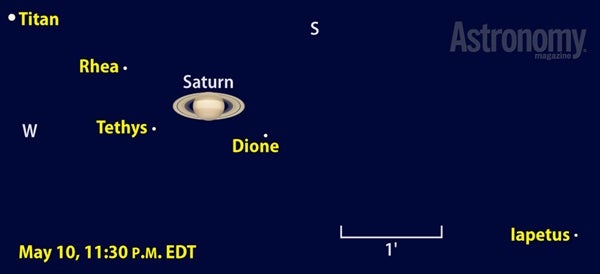

Saturn’s moons offer a similar range of observing challenges. The brightest moon, 8th-magnitude Titan, is an easy object through any telescope. It circles the planet once every 16 days, passing due north of Saturn on August 8 and 24 and due south on August 15 and 31. Between those times, Titan can stray up to 2.8′ from the planet.

Several smaller moons orbit Saturn in five days or less and remain within 1′ of the ring’s outer edge. The three brightest — Tethys, Dione, and Rhea — all shine at 10th magnitude and show up through 4-inch scopes on clear nights.

Distant Iapetus takes 79 days to complete a circuit of Saturn. With such an extended orbit, this moon rarely appears close to the planet. Your best bet for seeing it comes August 18, when it glows at 11th magnitude and lies 2.1′ due south of Saturn. The satellite then heads west and brightens slowly as its brighter hemisphere turns toward Earth. On August’s final night, it shines near 10th magnitude some 7′ from the planet.

As Mars and Saturn sink low in the southwest, Neptune ascends in the southeast. Although this distant world reaches opposition and peak visibility in early September, the view in August hardly suffers. It remains visible all night among the background stars of Aquarius the Water-bearer, climbing highest in the south after midnight.

Magnitude 7.8 Neptune shows up nicely through binoculars. It remains near 4th-magnitude Lambda (λ) Aquarii all month. On August 1, the planet lies 0.6° south of this star; by the 31st, it has moved to a point 1.2° southwest of Lambda. To confirm a sighting, point a telescope at the suspected planet. Only Neptune will show a noticeable blue-gray hue and, at high power with steady seeing, a 2.4″-diameter disk.

Uranus rises before 11 p.m. local daylight time for most of August and appears highest in the south as dawn breaks. The magnitude 5.8 planet is an easy target through binoculars and even shows up to the naked eye under a dark sky. You can find it in the southeastern corner of Pisces the Fish, a relatively sparse region that makes it quite easy to identify the ice giant planet.

First, locate 5th-magnitude Mu (μ) Piscium through binoculars. Uranus lies 2.5° north of Mu all month. Be careful not to confuse the planet with two slightly fainter stars closer to Mu. You can remove any doubt by pointing your telescope at the objects. Uranus shows a distinctive blue-green disk that spans 3.6″.

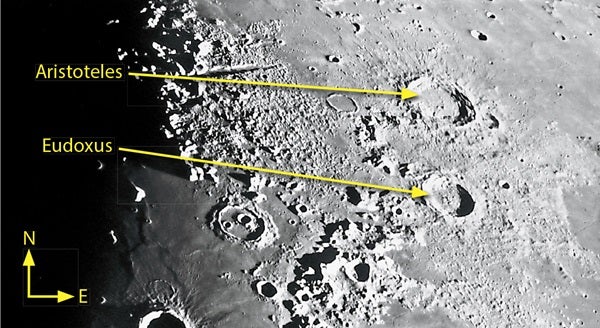

A couple of days before First Quarter phase, the Moon shows us a face of thirds. The south is a crowded, cratered mess that quickly morphs into the slate-gray maria that dominate the equatorial regions. A look at Luna’s northern third reveals an overall smoothness punctuated by a handful of large, identifiable craters.

On August 8, the rising Sun sets the ramparts of Aristoteles aglow even while the crater itself lies on the dark side of the terminator that divides day from night. One Earth day later, this marvelous crater appears fully lit except for a small shadowed zone tucked against its eastern wall, corresponding to the photo at right. Craters half its 55-mile diameter boast cleaner lines and a simpler peak, but Aristoteles’ features suffered more from the greater energy release of a large impact. In moments of good seeing, a lot of structure pops into view.

The blast excavated plenty of soil, which splattered down to create the large debris apron around Aristoteles as well as a huge number of small secondary craters. You can see them flit in and out of view only in the slanted light near lunar sunrise or sunset. By August 11, the higher lunar Sun has erased all evidence from view. The inside of the crater’s walls, weakened from the impact, slumped into a series of terraces. Millions of years later, lava welled up from beneath and flooded the inside, but not quite enough to cover the central peaks.

Return for a quick look around the August 17/18 Full Moon. The dark gray Mare Frigoris sweeps in a gentle arc across the lunar north while Aristoteles has been transformed to an oval of light material paired with the smaller, more circular crater Eudoxus just to its south.

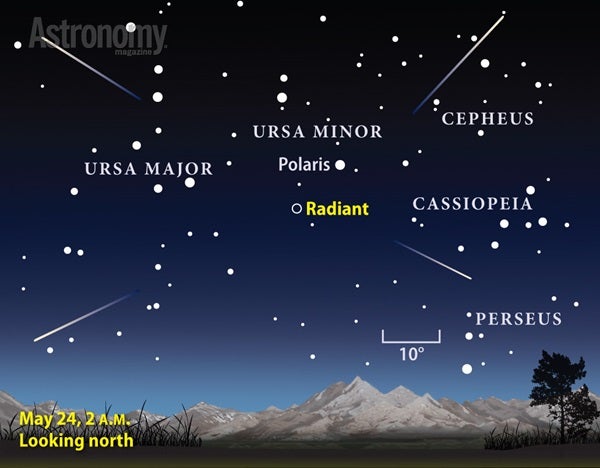

The annual Perseid meteor shower peaks the morning of August 12. Skies will be dark once the waxing gibbous Moon sets around 1 a.m. local daylight time. Just be sure to find an observing site far from the city so the meteors don’t have to contend with any of civilization’s artificial lights.

Although the Perseids usually rank among the strongest showers of the year, 2016 could be exceptional. Meteor scientists Mikhail Maslov and Esko Lyytinen think the background rate this year could reach 150 meteors per hour, some 50 percent higher than in typical years. The reason: Jupiter’s gravity recently nudged the stream of debris from the Perseids’ parent comet, 109P/Swift-Tuttle, closer to Earth’s orbit. Whether the prediction for increased activity pans out or not, the view should be spectacular as the shower’s radiant climbs high in the sky before dawn.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS |

||

| Evening Sky |

Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Mercury (west) |

Mars (southwest) |

Uranus (south) |

| Venus (west) |

Saturn (southwest) |

Neptune (southwest) |

| Mars (south) |

Uranus (east) |

|

| Jupiter (west) |

Neptune (southeast) |

|

| Saturn (south) | |

|

| Neptune (east) | ||

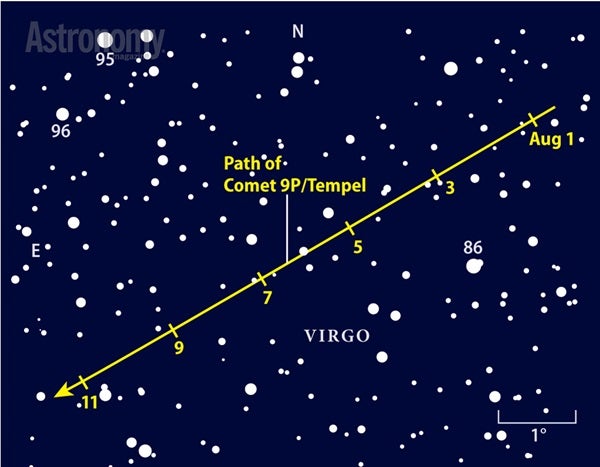

The hands of the celestial clock have aligned again for Comet 9P/Tempel. Eleven years and one month ago, thousands of amateur and professional astronomers locked their eyes and instruments onto this 4-mile-wide object, waiting with bated breath for a coffee-table-sized copper bullet carried by NASA’s Deep Impact probe to smack the nucleus. Two revolutions around the Sun later it has returned, mostly unharmed, to give us an 11th-magnitude fuzzball sailing eastward away from Spica.

It’s best to catch the comet during the first week of August before the Moon sheds too much light into the evening sky. For the same reason, try to get as far away from city lights as you can. Use the magnitude 5.5 star 86 Virginis, which lies 5° east of Spica, as your guide. Although a 4-inch telescope will show Tempel’s feeble glow, you’ll need an 8-inch scope to get a decent look.

The Deep Impact spacecraft revealed that the comet’s surface layer is mostly empty space — not the hard-packed ice-rock mixture that astronomers had expected. Another surprise: The water vapor and carbon dioxide spewing from the comet come out from different regions.

A second comet could be worth a look these August evenings. Although Comet PANSTARRS (C/2013 X1) glows a magnitude brighter than Tempel, it’s a tougher target for observers at mid-northern latitudes because it lies much lower in the sky. The haze and humidity common at this time of year conspire to obscure such objects near the horizon.

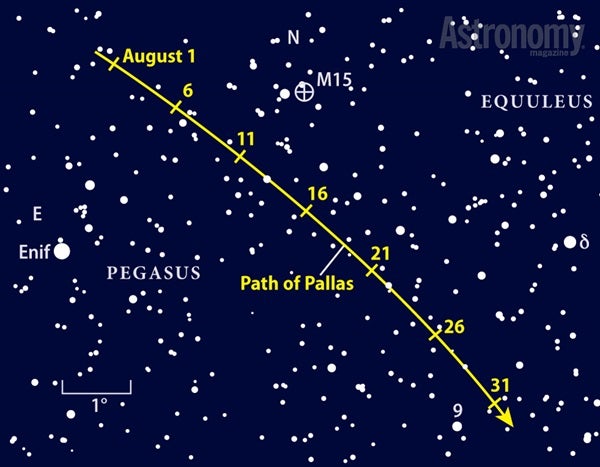

The first step in tracking down asteroid 2 Pallas is easy. Even from the suburbs, most people can readily find magnitude 2.4 Enif (Epsilon [ε] Pegasi). The bright star marks the nose of the Winged Horse and lies a bit west of that constellation’s Great Square. Pallas begins August 3° north-northwest of Enif and then heads southwest, passing between the star and the lovely globular cluster M15.

If you think of the Milky Way as a city, Pallas lies in the suburbs. The star density here is lower, so in principle it should be easier to find Pallas. But like the houses in some suburbs, the star fields in this vicinity can start to look alike. To find Pallas, carefully match the star patterns you see through your telescope with those on the finder chart below. To be sure you’ve pegged the asteroid, sketch the field where you think it is and then come back to it a night or two later. The object that has shifted position is Pallas.

The asteroid reaches opposition and peak visibility on August 20, when it shines at magnitude 9.2 and remains visible all night. Unfortunately, it now lies on the outer part of its elliptical orbit, so it appears about two magnitudes fainter than at a favorable opposition. German astronomer Heinrich Olbers discovered this main belt object in 1802.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.