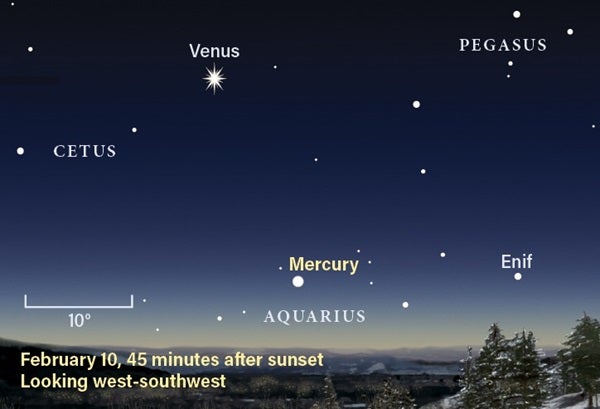

Let’s begin our tour soon after the Sun goes down in early February. On the 1st, you can find Mercury 7° high in the west-southwest a half-hour after sunset. Shining at magnitude –1.0, the planet is easy to see if you have a clear sky and unobstructed horizon. It lies against the backdrop of much fainter stars belonging to Aquarius the Water-bearer. Look for these stars as Mercury sinks lower and the sky darkens.

The inner world climbs higher each evening until it reaches greatest elongation February 10. Mercury then lies 18° east of the Sun and stands 11° high 30 minutes after sunset. Although it has faded slightly, to magnitude –0.6, the greater altitude makes it easier to spot. The combination of brightness and altitude makes this the planet’s finest evening appearance of 2020.

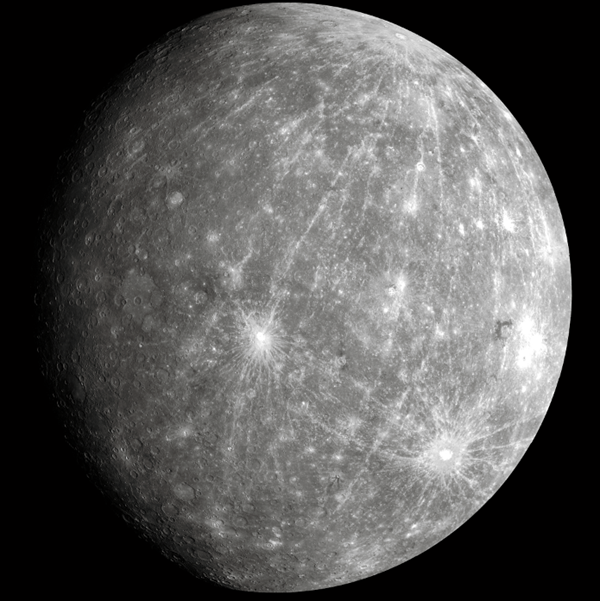

After its peak, Mercury dips lower and dims noticeably with each passing night. You can follow it for another week or so; on the 17th, the magnitude 1.2 world hangs 8° high a half-hour after sundown. A telescope then reveals a disk 9″ across and less than 20 percent lit.

Like Mercury, Venus begins the month in Aquarius. The Water-bearer can’t hold its prize for long, however, and Earth’s twin crosses the border into Pisces the Fish on February 2. Venus, which brightens from magnitude –4.1 to –4.3 during February, appears more than 500 times brighter than any star in either constellation.

The planet dazzles even more than usual this month because it shines against a dark sky. Although you can spy it easily within a half-hour after sunset, it appears 20° high as the last vestiges of twilight fade away on the 1st and 5° higher by the 29th, when it doesn’t set until after 9:30 p.m. local time. The increasing altitude is a sign that Venus is approaching its own greatest eastern elongation and peak visibility, which it will reach in late March.

February’s final week features a close encounter between the night sky’s two brightest objects. The waxing Moon first comes into view on the 24th, when it appears in twilight and sets about an hour after the Sun. The next evening, it’s a lovely thin crescent standing 10° high an hour after sunset with Venus 20° above it. The gap between the two closes to 10° on the 26th and 7° on the 27th. The two make a stunning pair visible for two to three hours both nights.

Venus’ appearance through a telescope doesn’t change as rapidly as Mercury’s, though Earth’s next-door neighbor is still worth tracking. During February, Venus’ apparent diameter grows from 15″ to 19″ while its illumination shrinks from 73 to 63 percent. Your best views will come during twilight, when the contrast between sky and planet is less intense.

You can use Venus and Mercury as guides for finding Neptune in early February. A line between the two inner planets traces the ecliptic — the Sun’s path across our sky that the planets follow closely — and intersects the position of the solar system’s most distant major planet.

The separation narrows in the days ahead. On the evening of the 10th, Neptune skims just 2′ north of Phi. That’s slightly less than the distance between Io and Jupiter when the innermost jovian moon reaches greatest elongation. Alas, you won’t be able to follow the pair for much longer — the two succumb to low altitude and twilight after mid-February.

Uranus fares far better than Neptune because it’s seven times brighter (magnitude 5.8) and much higher in the sky. Binoculars easily gather enough light to reveal this ice giant — the challenge comes from the fact that it lies in a sparse region of the sky with few signposts. To get to the right area, first find magnitude 2.0 Hamal (Alpha [α] Arietis). The brightest star in Aries the Ram appears two-thirds of the way from the southwestern horizon to the zenith once darkness falls in early February. Uranus lies 12°, or nearly two binocular fields, south of Hamal.

As with Neptune, Uranus reveals its true nature through modest telescopes. The seventh planet sports a distinctive blue-green color on a disk that spans 3.5″.

If you follow the evening planets all month, you’ll notice Venus climbing higher while Uranus dips lower. Forty degrees separate the two February 1, but the gap shrinks to 8° by the 29th. The two are destined for a close meeting during the second week of March.

Uranus sets around midnight local time in early February and some two hours earlier by month’s end. Planet lovers can then get some shut-eye before the next planet rises several hours later.

Mars appears first, poking above the southeastern horizon shortly before 4 a.m. local time. Because the Red Planet travels eastward along the ecliptic at nearly the same rate as the Sun, its rising time changes little during the entire month. On February’s first morning, magnitude 1.4 Mars lies in Ophiuchus the Serpent-bearer. Don’t confuse it with its ancient rival, Antares, which rises about a half-hour earlier and appears 11° west (upper right) of Mars. Although the two objects have a similar hue, the star shines slightly brighter than the planet.

You can view this stunning occultation with your naked eyes, but binoculars or a telescope reveal far more detail. Use a scope if you want to watch Mars fade away as the Moon’s bright limb gradually overtakes it. Depending on your location, the Moon can take up to 15 seconds to completely cover the Red Planet’s featureless, 5.2″-diameter disk.

The event occurs earlier the farther west you live. Although Mars disappears before the two objects rise along the West Coast, observers there can witness the planet’s equally stunning reemergence from behind the Moon’s dark limb. Those in the mountain states get to view the disappearance against a dark sky, while Midwesterners see the same event during twilight. Unfortunately, East Coast skygazers miss out because the occultation occurs after the Sun rises. Even so, they’ll enjoy a beautiful close conjunction between the two objects before dawn. You can find precise times for the occultation on the International Occultation Timing Association’s website at http://occultations.org.

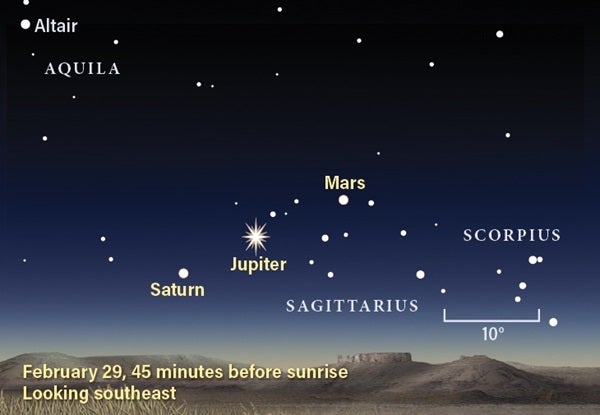

Two more planets emerge closer to dawn. Jupiter rises about 90 minutes before the Sun on February 1, and Saturn follows 40 minutes later. The two stand 11° apart in Sagittarius, with Jupiter shining at magnitude –1.9 and Saturn at magnitude 0.6.

After the Moon occults Mars on February 18, it slides 4° to Jupiter’s right on the 19th and 2.5° to Saturn’s lower right on the 20th. This splendid three-day stretch should prove unforgettable for early risers.

By the end of February, all three planets rise before twilight begins. They spread out 19° along the ecliptic, with Mars highest, Jupiter 10° to its lower left, and Saturn 9° farther on.

With the giant planets at such a low altitude, you’ll be hard-pressed to get sharp views of them through a telescope. Even at the end of February, Jupiter’s 34″-diameter disk likely will show only its two dark equatorial cloud belts. And although you’ll be able to see Saturn’s ring system, which spans 35″ and tilts 22° to our line of sight, it won’t look nearly as spectacular as it will in the coming months.

Rising Moon: The mark of the Ram

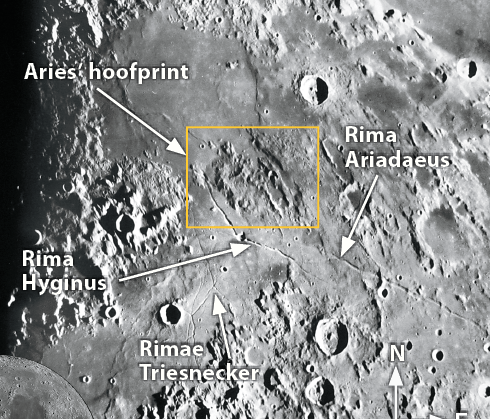

The First Quarter Moon stands high in the southwest once darkness falls February 1. Earth’s satellite appears against the backdrop of southern Aries. Coincidentally, if you aim a telescope at the Moon this evening, you could almost convince yourself that the Ram had sauntered across the lunar surface and left behind a large hoofprint.

On February’s first evening, the Sun has just risen over a fascinating series of long, narrow channels known as rilles, highlighted by Rima Ariadaeus, Rima Hyginus, and the rille complex Rimae Triesnecker. But what really catches the eye in this area just north of the equator is a delightful feature dubbed “Aries’ hoofprint.” The combination of brightly lit mountains and two deep channels of especially dark lava creates this striking play of light and shadow. At low power with the entire half-lit Moon in view, the hoofprint stands out.

It’s easy to understand why lunar cartographers didn’t label this feature on their maps. After all, it’s only a jumble of mountains left over from the giant impact that created Mare Imbrium with a lava channel on either side. Furthermore, lunar scientists focused on Rima Hyginus with good reason — this series of small pits is almost certainly volcanic in origin. It stands out nicely on the 1st because one of the rille’s walls is brightly sunlit while the other remains in shadow.

Sadly, Aries’ hoofprint doesn’t stand out for long. By the evening of February 2, the Moon has moved on to Taurus, and the increasing glare of the Sun has reduced both the Ram’s artifact and Rima Hyginus to mere echoes of their previous magnificence.

Meteor Watch: Discover the zodiac’s elusive glow

The longest lull in the yearly meteor calendar runs from early January (the brief but prolific Quadrantids) to late April (the more modest Lyrids). But meteor enthusiasts shouldn’t abandon all hope this month. Many ancient meteor streams that dispersed long ago create a sporadic background rate of about a half-dozen meteors per hour, with the best views coming before dawn.

Meteoritic dust also shows up on February evenings, but in a completely different form. The dust ejected by comets fills the inner solar system and concentrates along the orbital plane of the planets. On dark February evenings, you can catch sunlight glinting off this debris.

The zodiacal light is a cone-shaped glow that appears above the western horizon once evening twilight fades away. Roughly as bright as the Milky Way, the zodiacal light passes through Aquarius, Pisces, and Aries. (This year, Venus sits in the middle of the glow.) Look for the zodiacal light from a dark site when the Moon is gone from the evening sky, from February 10 to 24.

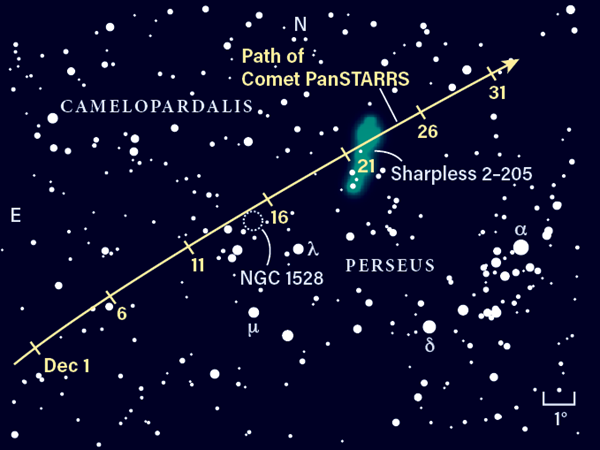

Comet Search: Taking Stock with the Heart and Soul

Comet PanSTARRS (C/2017 T2) enjoys a series of close encounters with impressive deep-sky objects this month. The comet moves slowly northward along the Milky Way near the Perseus-Cassiopeia border. It begins February 1° northwest of the Double Cluster, curves around the pretty binocular cluster Stock 2 around midmonth, and closes the month a few degrees west of the Heart and Soul nebulae (IC 1805 and IC 1848, respectively). This all makes for a stunning backdrop for wide-field images.

PanSTARRS’ northern location makes it a circumpolar object for observers across most of the U.S. Still, it lies highest in the sky early in the evening and dips low in the north after midnight, so plan to observe it shortly after darkness falls. The best Moon-free window occurs between February 11 and 26.

Astronomers expect the comet to glow around 8th or 9th magnitude this month, on its way perhaps to 7th magnitude at its peak in May. Through 12-inch and larger telescopes, you might pick up the comet’s subtle greenish hue.

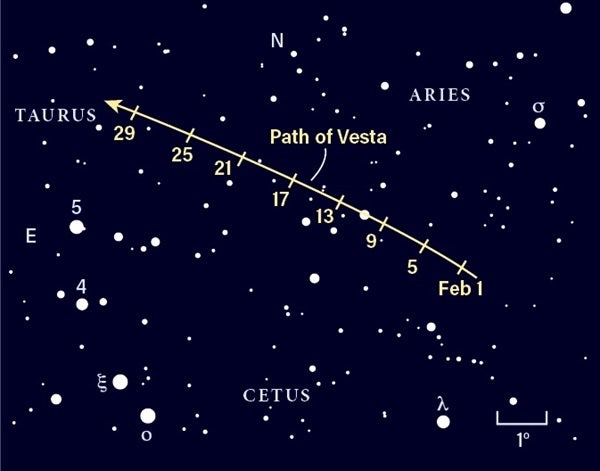

Locating Asteroids: Grabbing the Bull by its toes

Asteroid 4 Vesta is nothing if not reliable. Although it is not the largest object in the main asteroid belt, it is consistently the brightest. For that, we can thank its high reflectivity and its relatively close orbit to the Sun.

Vesta lies some 20° — about three binocular fields — west of 1st-magnitude Aldebaran in Taurus. If you think of the V-shaped Hyades Cluster as an arrowhead, it points to the west. Our guide stars are Omicron (ο) and Xi (ξ) Tauri — two 4th-magnitude suns that lie in far western Taurus and form one of the Bull’s front feet.

You’ll want to hunt for the 8th-magnitude asteroid in the early evening when this region lies high in the southwest. Vesta should be fairly easy to pick out because it glows brighter than most of the surrounding stars. Confirming an asteroid sighting requires seeing it move relative to the starry background, however. Typically, this means sketching the field of view one evening and then returning the following night to see which object changed position. But you’ll be able to see Vesta move in a single night February 11 when it passes within 2″ of a magnitude 5.6 field star.

On February 1, the First Quarter Moon occults Vesta for observers in Alaska and Western Canada. While a star disappears instantaneously behind the Moon’s limb, Vesta’s 0.3″ angular diameter makes it fade away over nearly a second.