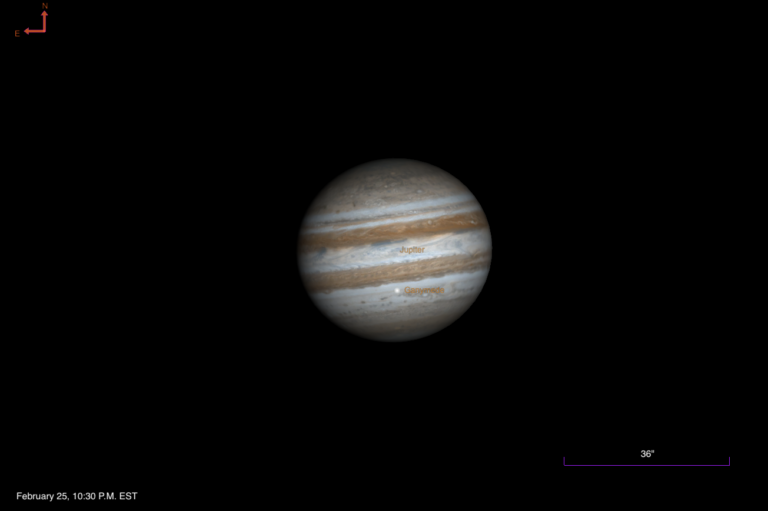

Let’s tour each planet from sunset to dawn throughout the month. First up is Venus, visible even before sunset if you look carefully. As the month opens, Venus is about 30° high in the west. After Venus pops into view in the falling twilight, how long does it take you to spot Jupiter, just 30′ to its southeast? The evening of March 1 in the U.S. is slightly before the true conjunction, which takes place when the giant planet is due north of Venus. That formal moment of conjunction occurs the morning of March 2, well after the pair has set in the U.S.

The contrast of this planetary duo is stunning. Try your first view in twilight before the dazzling brightness of Venus overwhelms easy observation of its disk. Use low magnification and aim for about a 1° field of view to see both planets together. Venus, an Earth-sized planet, reveals an 86-percent-lit disk spanning 12″. Jupiter is attended by its three of its four Galilean moons; Europa is hidden behind the giant in the early evening and even when it’s clear of the limb, it remains within Jupiter’s vast shadow. Europa reappears soon after 7:10 P.M. PST for West Coast observers, long after the planet has set for the eastern half of the country.

Venus lies 1.37 astronomical units (127 million miles) from Earth. (One astronomical unit, or AU, is the average Earth-Sun distance.) Jupiter, on the other hand, is nearly five times farther, 5.78 AU (537 million miles) away. Even at this huge distance, Jupiter sports a larger diameter of 34″, conveying its true dominant size in our solar system.

Set against the faint constellation Pisces the Fish, there are no other bright stars in this region of the sky. The planetary duo sets before 8:30 P.M. local time. After March 1, the nightly view shows the pair of planets separating. Jupiter continues to fall toward the Sun, so to speak, as it heads for conjunction later in the spring. Venus, on the other hand, continues to climb and extends its angular separation from our star. By midmonth, it crosses into Aries the Ram.

Look low in the west on March 22 for Jupiter and a crescent Moon, less than 2° apart. They set about 70 minutes after the Sun. The following evening, the Moon hangs 6° below Venus in another lovely pairing. Try photographing this scene in twilight with interesting foreground objects to create an artistic silhouette against the sky.

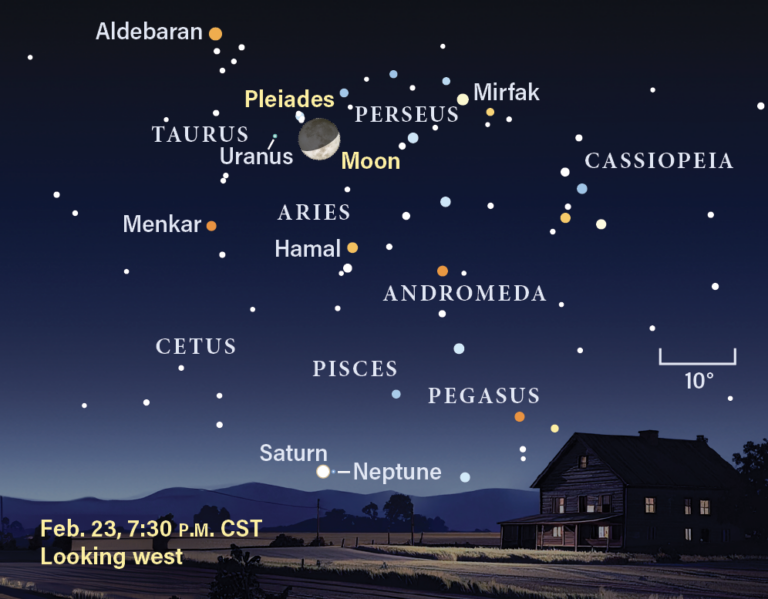

As a prelude to the Venus-Uranus conjunction, the wandering crescent Moon and Uranus stand less than 1.5° apart on March 24. Grab binoculars to view the lovely crescent Moon, then scan southward to find the dim planet shining at magnitude 5.8. Uranus is close to a 7th-magnitude field star just 4′ away. Attentive observers in some U.S. locations will spot the disappearance and reappearance of 6th-magnitude Rho (ρ) Arietis in an occultation by the Moon that takes place from approximately 7:30 P.M. to 8:10 P.M. local time. (You’ll want to check precise predictions, as whether the event is visible and its exact timing are affected by your geographic location.)

By March 30, Venus is in conjunction with Uranus. With binoculars, you can find Uranus standing 1.2° due south of Venus. Venus now shows a 78-percent-lit gibbous disk spanning 14″. The much more distant Uranus (20.45 AU; 1.9 billion miles) spans 3″. The following night, the last evening of March, the two planets are still less than 2° apart. They set before 10:30 P.M. local time, so plan your viewing soon after dark.

Uranus is an easy binocular target all month, starting March near Sigma (σ) and Pi (≠) Arietis, a pair of 5th-magnitude stars about 12° due north of Menkar in Cetus the Whale. On March 1, the planet is located midway between these two stars; from night to night, it wanders northeastward. It passes close to a 6th-magnitude field star on March 15, then enjoys its meeting with the Moon on the 24th and with Venus on the 30th.

Mars blazes brightly in Taurus the Bull, outshining magnitude 0.9 Aldebaran for most of March and ultimately fading to match the red giant star by the end of the month. The Red Planet’s nightly path carries it roughly midway between the horns of the Bull, marked by the stars Zeta (ζ) and Beta (β) Tauri, on March 11. It crosses into Gemini March 26.

In the first week of March, Mars spans 8″. During this week, the features facing earthward around midevening include the Tharsis ridge and Olympus Mons. By mid-March, the planet has shrunk to 7″ and Valles Marineris and Solis Lacus are prominent. In the third week of March, Sinus Meridiani and Sinus Sabaeus are on display.

On March 29, Mars stands 1.1° due north of the fine open star cluster M35 in Gemini. The view in binoculars is worthwhile, and a rich-field telescope reveals a star-studded field of view along with the brilliant orange glow of Mars, now magnitude 0.9. The prominent dark feature Syrtis Major is coming onto the Earth-facing disk at the end of March during early evenings.

The best views of Mars occur a couple of hours after sunset, with Mars very high in the sky. By the end of March, Mars sets before 2:30 A.M., allowing ample time for observers to test their skills on a tiny disk.

Hours pass between when Mars sets and another planet appears in the sky. Mercury is a difficult object in the morning sky in early March. On March 2, it’s in conjunction with Saturn, which is reappearing after last month’s solar conjunction, but the event won’t be visible for most observers in North America. Mercury shines at magnitude –0.6 and Saturn is fainter at 0.8. The difficulty is that this conjunction takes place only 13° west of the Sun when the ecliptic is at a low angle to the horizon; furthermore, the pair rises less than 20 minutes before the Sun, rendering the sky too bright to see them.

Mercury sinks toward its March 17 conjunction with the Sun and reappears in the evening sky in a more favorable apparition where the ecliptic is steeply inclined to the western horizon. Look for it March 27 some 30 minutes after sunset, shortly before its near conjunction with Jupiter occurs. Mercury shines at magnitude –1.5 and Jupiter, located 1.3° to its right (northwest), is still magnitude –2.1. The two stand just 3.5° high and set within 20 minutes. Find a location with a horizon that is clear of obstructions such as trees and buildings for a good view of this conjunction.

Saturn, meanwhile, continues to extend its angular separation from the Sun and by March 31 rises 75 minutes before dawn. You’ll find it low in the east an hour before sunrise, now located in Aquarius.

Neptune is not visible this month and passes through solar conjunction on March 15.

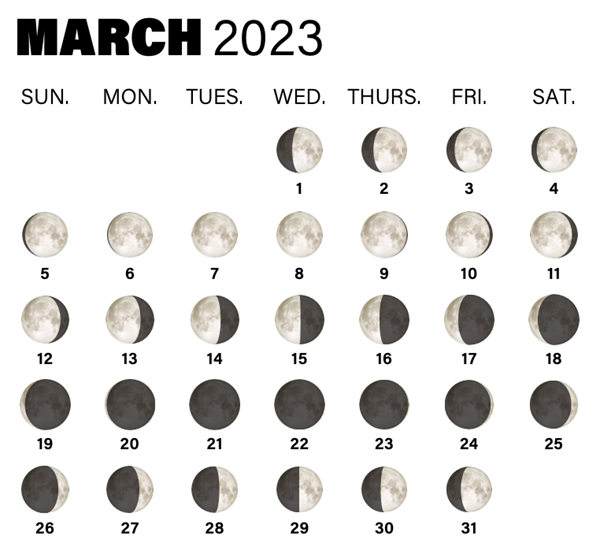

Rising Moon: More than meets the eye

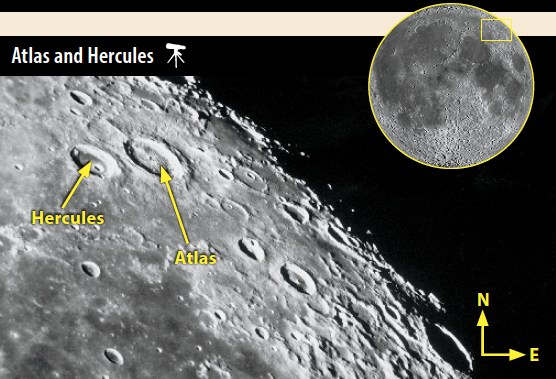

What can compare to the fantastic chain of lunar features along the day-night terminator of a five-day-old Moon? Viewing the lunar surface through a telescope is the closest we’re going to get to experiencing Buzz Aldrin’s magnificent desolation. On the evening of the 26th, Posidonius and the Serpentine Ridge dominate the northern half, while the bright-rimed black hole of Theophilus catches the eye at the equator.

The true extent of the mighty blast that carved out the Nectaris basin is revealed at this low Sun angle. The Sea of Nectar is defined by the darker plains of lava that bubbled up from below through the cracks in the basin floor. A feature like this is much more complex than a simple bowl with a central peak and much larger than what first greets the eye.

The true rim of Nectaris stands out in the form of the Altai Scarp, a bright arc that disappears southeastward under the more recent crater Piccolomini. As the Sun continues to rise, the northern part of Altai is slowly revealed over the next hours and appears quite noticeable on the following night.

Reverse lighting occurs when the waning gibbous Moon rises barely before midnight, with the tall rim of the scarp casting stark black shadows. Look on March 10th and 11th to see it, or again on April 9th and 10th.

Meteor Watch: Dust causes false dusk

Spring is relatively devoid of meteor showers

until April, but this lull in activity is replaced by ideal circumstances to observe the zodiacal light. Our solar system is littered with eons’ worth of debris from passing comets. This dust tends to settle into the orbital plane of the solar system. Well after sunset in March, with the ecliptic angled very steeply to the horizon, this subtle, diffuse light from billions of particles is clear to see from dark locations well away from streetlights.

As the long, low arc of twilight fades across the western horizon, watch for an extended cone of light stretching up through Aries and Taurus, almost as bright as the Milky Way if you’re in a dark location. Any cities to your west will obliterate the view. Observers who can reach higher elevations are at an advantage thanks to less atmospheric scattered light, which subdues the zodiacal glow. The best time to look is after the early March Full Moon. Make your attempt between March 10 and 23, which is when the Moon reappears in the evening sky.

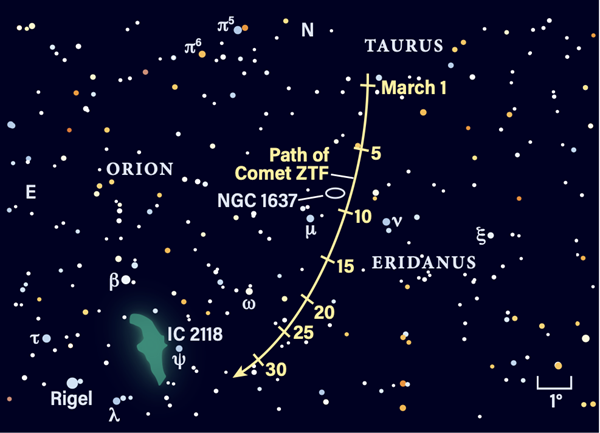

Comet Search: Bewitched by the green glow

Picture a dolphin jumping over the back half of your cruising boat and diving deep — that trajectory is similar to Comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF)’s passage by Earth. We rapidly turn our gaze at first, then almost stop panning as we watch it fade into the depths.

Last month’s peak performance is done, but it’s not the end of the show. ZTF displays a broad but short diffuse fan of dust spreading northward, with a sharp southern flank. Before moonrise on the evening of March 10, the comet is a mere 10′ from the star-filled spiral galaxy NGC 1637. The next night, it’s still on the edge of a medium-power eyepiece field centered in the same spot. Compare and contrast their shapes and the distribution of their light under country skies with a 6-inch or larger scope. Which of these 10th-magnitude objects is brighter?

West of Orion’s blazing foot Rigel, ZTF descends between 4th-magnitude Mu (μ) and Nu (ν) Eridani, curling toward the famous Witch Head Nebula (IC 2118). The green glow of the comet’s coma punctuates a 6°-wide-field shot here during New Moon.

Locating Asteroids: Sirius won’t fetch Pallas

The celestial dog Canis Major pays no attention to the modestly bright 8th-magnitude starlike dot passing north of its blazing heart, Sirius. The second asteroid to be discovered, 2 Pallas tracks into Monoceros the Unicorn after midmonth. On your way to observing our main-belt target, stop by the star clusters M50 and M41 (the latter is just south of this field of view; see last month’s chart).

A 4-inch scope from the suburbs will readily reveal Pallas, but your go-to scope might land you on a field with quite a few stars. Which one is the impostor? The tried-and-true method is to make a quick four-star sketch and come back two hours — or one or more nights — later to see which one shifted. On the positive side, there are many nights where Pallas is the brightest object in the field.

Did you know that asteroids commonly masquerade as supernovae? Tracking across Coma Berenices, 1 Ceres skims the outskirts of galaxy M91 on the 11th, then slides across the arms of the open-face spiral M100 on the 26th. Both galaxies lie far beyond the Milky Way itself, in the Virgo Cluster. We’ll feature the brighter Ceres for a few months beginning in April.