Neither Dave nor Martin had noticed Izar’s pop-up neighbor before. In fact, I had stumbled upon it myself only recently. Nevertheless, seeing their surprise comforted me because I had reacted the same way. It helped me realize that without the element of surprise, our hobby would be somewhat mundane. To paraphrase the fictitious FBI Special Agent Fox Mulder in the 1998 movie The X-Files: In a universe of infinite possibilities, we should anticipate the unforeseen and expect the unexpected. Perhaps that’s why Dave suggested I share this “stellar” surprise — to help you, too, expect the unexpected.

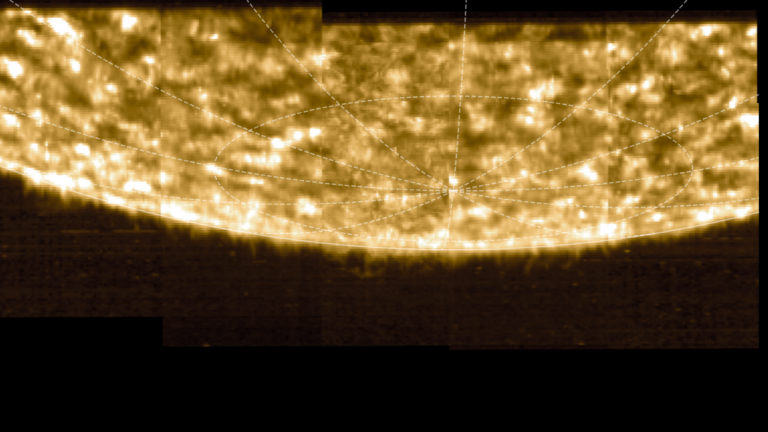

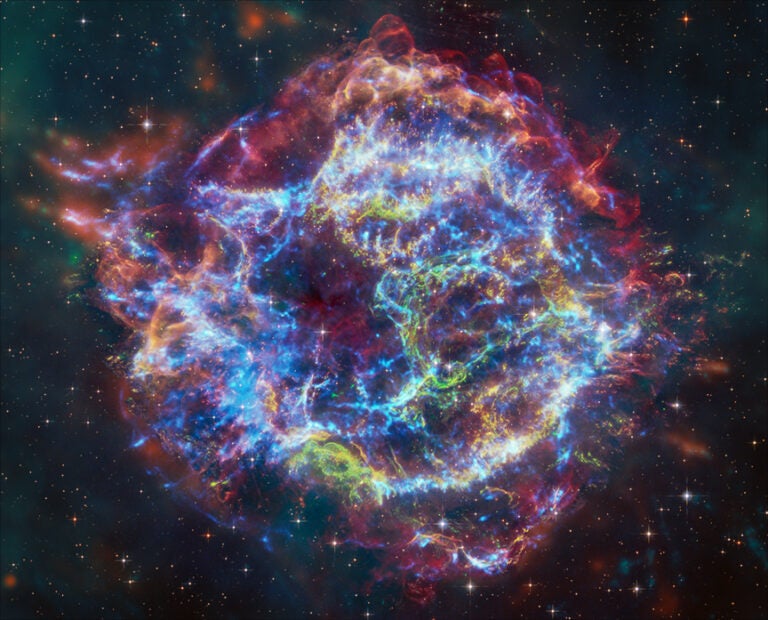

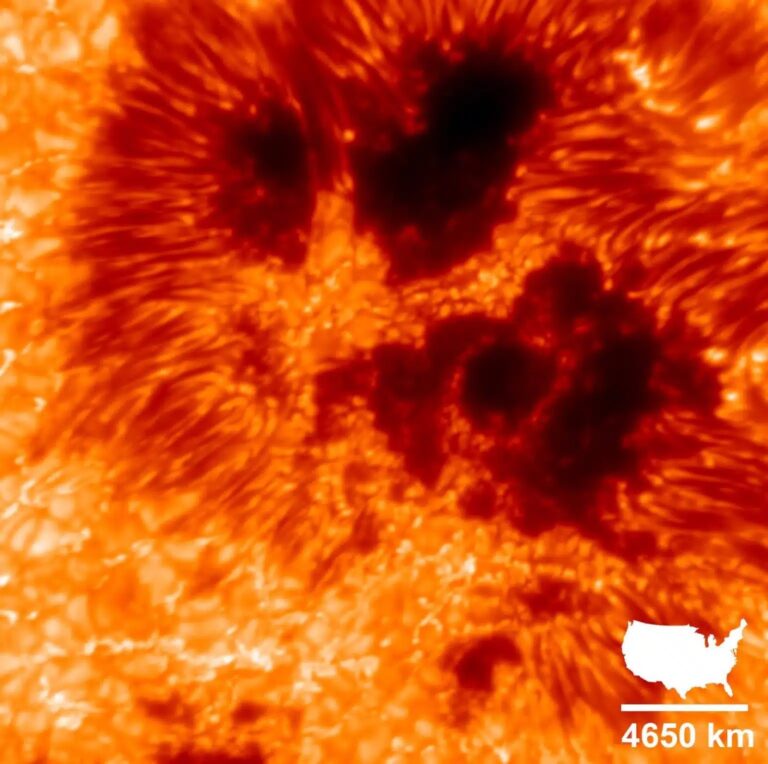

Izar’s naked-eye companion is W Boötis (also known as 34 Boötis) — a semiregular variable star whose brightness ranges from magnitude 4.7 to 5.4 over an unpredictable time period. The star, a class M3 red giant, has a diameter some 130 times that of the Sun and a luminosity nearly 3,000 times greater. It’s an old star, most likely in a “pre-helium flash” phase, before it evolves into a white dwarf surrounded by a planetary nebula.

From 1966 to 1990, W Boötis pulsed with a period of about 25 days. Then, from 1991 to 1994, its period seemed to change to about 50 days, but these observations became muddled when it turned out the comparison stars were themselves variables! In 1996, new studies suggested staggered periods of 25 and 33 days.

Whatever its period, the good news is that whether the star shines at minimum or maximum light, it stays within naked-eye range. But W Boötis easily escapes notice because it lies only 40′ southwest of brighter Izar, which can easily steal our eyes’ attention. Besides, the variable comes to “light” only by using averted vision, especially when it’s dimmest.

Still, I’d love to hear what you see (or don’t see). In January 2008, I detected W Boötis with direct vision when, according to Elizabeth Waagen at the American Association of Variable Star Observers, the star’s magnitude was about 5.1.

Izar’s other buddy

Although Izar and W Boötis lie close together in our perceived two-dimensional sky, they are not physically related. Izar lies at a distance of about 200 light-years, while W is nearly 4.5 times farther away. Like marigold-colored Arcturus (Alpha [α] Boötis), the brightest star in the north celestial hemisphere, Izar is a full-fledged K-type orange giant. However, I find Izar looks more lemon yellow than golden through my 5-inch f/5.2 Tele Vue refractor; W Boötis, on the other hand, shines like a warm golden flame.

Izar was one of many double stars that William Herschel discovered and monitored over the course of some 2 decades. In an 1803 paper, Herschel noted that changes in the relative positions of these pairs (including Izar) proved that many are “not merely double in appearance, but must be allowed to be real binary combinations … held together by the bond of mutual attraction.”

Splitting Izar has been considered a “test” for beginners with apertures up to 6 inches. Nevertheless, the experienced 19th-century British observer Rev. Thomas W. Webb saw it “perfectly” with a 2¼-inch refractor. The key to success is to observe on a night of good seeing (one with bright moonlight or in the twilight), exercise patience, and use sufficient magnification.

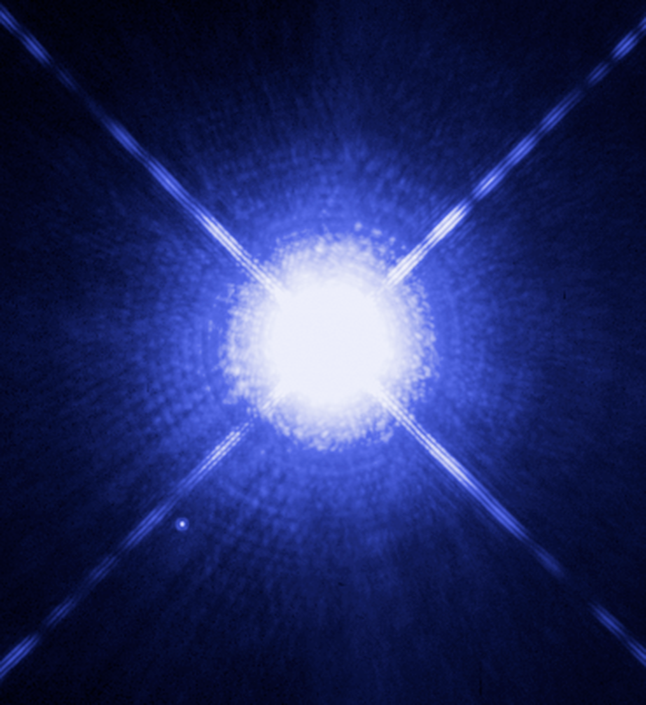

As dawn approached and the seeing steadied, Izar’s companion revealed itself stunningly at powers of 165x and 330x. Once I knew where to look, I could also separate the two stars at powers as low as 94x. I could not convince myself of the star’s duplicity at 60x, however.

Worlds apart

More than 2 centuries ago, Herschel penned that Izar “has much the appearance of a planet and its satellite, both shining with innate but different light.” Indeed, my first impression of the pair was one of a distant Sun-like star with a wondrous water-world orbiting it. And I’m not alone: The late astronomy popularizers Agnes Clerke and Camille Flammarion described the primary as “chrome yellow” and “bright yellow,” and the secondary as “sea-water blue” and “marine blue,” respectively.

Is it surprising then that, in the early 1970s, Scottish science-fiction writer Duncan Lunan caused an international commotion when he claimed to have translated signals from a spacecraft sent to the Moon in the 1920s by the inhabitants of a planet orbiting Izar? Lunan’s translation of the alien message begins: “Our home is Epsilon Boötis, which is a double star.” Among other media, the story made it to the CBS Evening News and Time magazine. Although Lunan has since withdrawn most of this idea, it remains a testament to the power and intrigue of this amazing star.

As always, send your thoughts and reports to someara@interpac.net.