Blinded by the light?

Revere’s journey began in Boston’s North End, where two friends rowed him across the narrow part of the Charles River that separates the North End from Charlestown. The crew members faced a formidable challenge: They needed to row unnoticed past the huge British ship the HMS Somerset, which England had stationed there to prevent any such attempt.

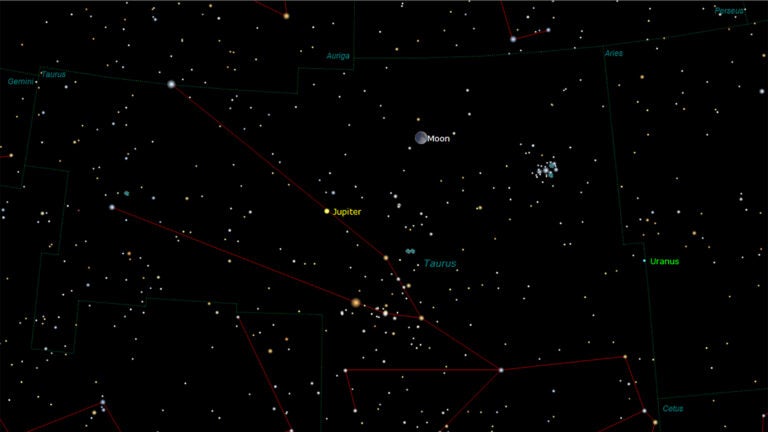

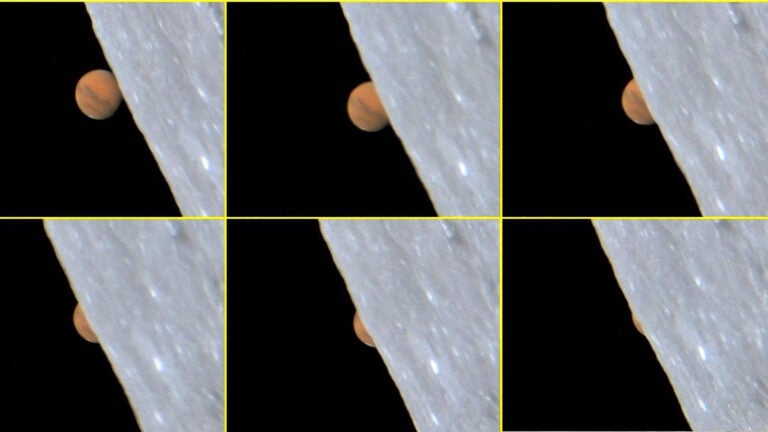

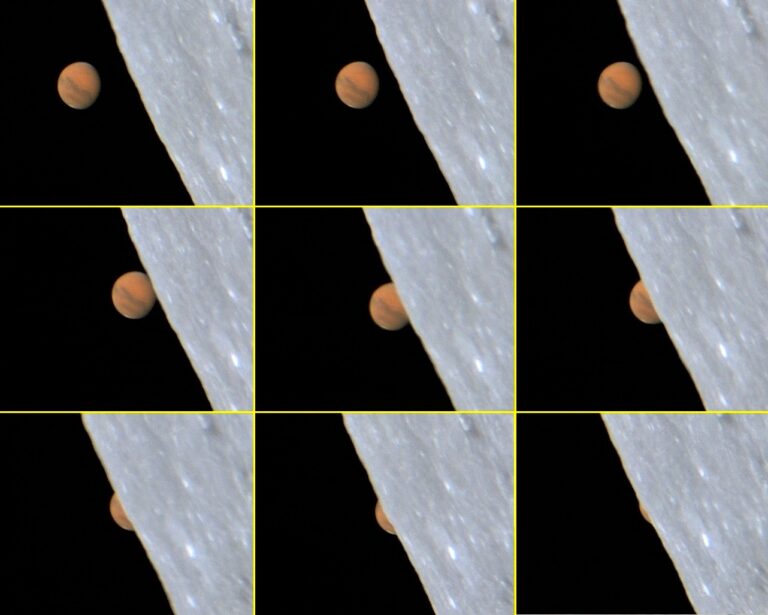

When Revere and his friends made the crossing at around 10 p.m., a bright waning gibbous Moon stood 6° above the east-southeastern horizon. It is possible that this was not a coincidence but instead strategy: With the Moon behind him, Revere could use its light to navigate to shore, which would have been difficult to achieve in complete darkness.

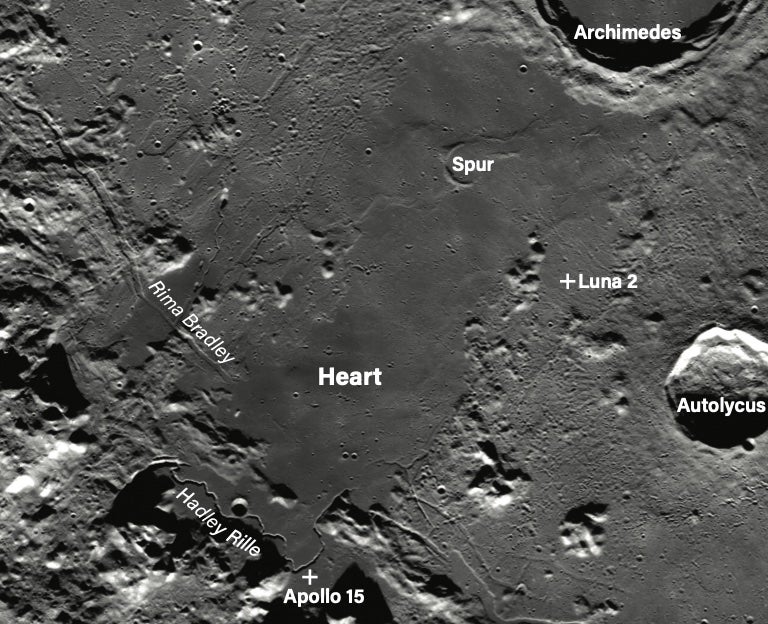

In 1798, Revere recalled in a letter to American historian Jeremy Belknap that the patriots rode “a little to the eastward where the Somerset Man-of-War lay.” This was a brilliant strategy. When we look in the direction of a nearly Full Moon that is close to the horizon, the landscape before us becomes difficult to interpret due to intense contrast effects that create bright areas next to those deep in shadow. At the same time that the Moon’s light assisted the patriots safely to shore, its enhancement of contrast must have hindered sentries on the Somerset from seeing the stealthy small boat.

The Moon was positioned well for a glitter path — a line of lunar reflections that appears on rippling water — to occur. That collection of reflections would have shown the sentries a rowboat in silhouette had the path not been oriented east-southeast to west-northwest — tangential to the northward path of Revere’s boat. If a sentry had taken note of the rising Moon and its glitter path, his gaze would have been averted from the passing patriots. Looking at a bright Moon would have ruined his dark adaptation and adversely affected his peripheral vision’s acuity.

Once he was on horseback, Revere rode into an increasingly well-moonlit night. Around 11 p.m., when he was approaching Cambridge, he recalled that “the moon shone bright.” According to his own account, he encountered “two Officers on Horseback, standing under the shade of a Tree.” Before he noticed them, Revere had gotten “near enough to see their Holsters & Cockades.”

This passage shows that the British troops had their own effective moonlight strategy. By avoiding direct or reflected rays from our satellite, the soldiers blended in with the forest’s dappled shadows. The great difference in contrast between lit and shadowed areas created a splendid camouflage. Allied World War II pilots used a similar technique to avoid detection by enemy planes flying above them when they were passing over moonlit water.

In Cambridge, the roles were reversed from the way they had been earlier in the night. Revere now had the disadvantage of being a moving target exposed to the light of a high Moon while the British stood motionless and unperceived in the shadows. So clever was this Red Coat tactic that Revere did not notice his enemy until he could distinguish detail in their wardrobes, which means he was right on top of them. Revere was able to use his horsemanship, however, to escape. He was, unfortunately, not so lucky in Lexington, when he rode into the same shadow trap and was captured.

As Revere learned, what happens in the sky above can make or break what happens here on the ground, which is as true today as it was then.

As always, send any comments or insights to me at sjomeara31@gmail.com.