Dissecting an enigma

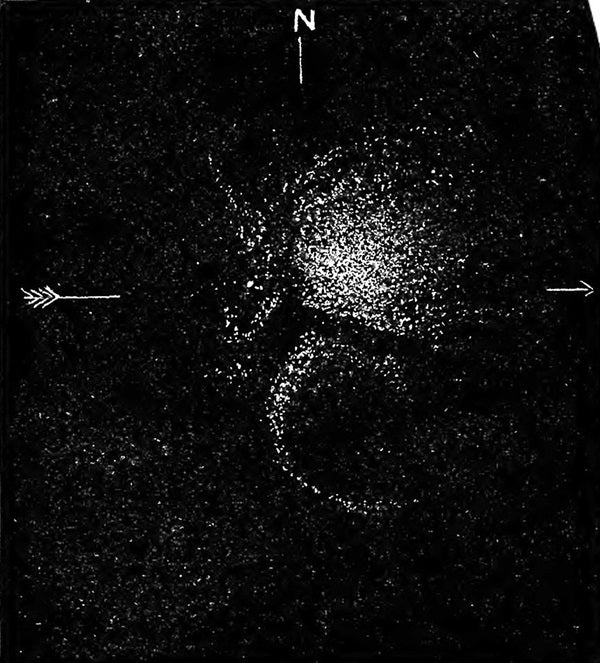

A sketch by Rosse’s assistant, Bindon Stoney, shows the propeller’s position, which at a glance appears to lie near the cluster’s center. But does it?

In 1887, Mark W. Harrington spent a month visually studying these dark lanes through the 6- and 12-inch refractors at the Detroit Observatory in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The astronomer did so with the aid of H.C. Markham, an artist whose sight Harrington found to be remarkably keen.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

At first, they found the rifts “somewhat difficult objects.” As Harrington notes in an 1887 issue of The Astronomical Journal, “They are so elusive that I sometimes almost doubted their existence, but I found that with patience I could always see them.” High powers (500x to 600x) produced the best results.

But Harrington noted a curiosity: In Stoney’s drawing, the radiating point of the rifts is nearly central; in Markham’s, it is southeast of the cluster’s core. “Whatever the rifts are,” Harrington concluded, “it seems certain that they have shifted their position slightly” since Stoney’s drawing was made. But did they actually move?

No astronomical artist accurately plots the positions of tens of thousands of stars in a globular cluster’s core. Instead, we see an artist’s interpretation of the view. In Stoney’s representation, the stars east of the propeller’s center are brighter and more numerous than those in the Markham drawing. Furthermore, the outer stars in the region northwest of the propeller’s radiant are fewer in Stoney’s representation than those depicted in the Markham drawing.

To figure out what was going on, I used Photoshop to add stars to the Stoney drawing to enhance the core’s outer region northwest of the propeller’s radiant. Then I darkened the core region east of the propeller’s center. The result: The propeller’s position in Stoney’s drawing better resembles that in the Markham drawing. Any confusion, then, boils down to artistic impression of starlight, not the movement or misrepresentation of the dark propeller’s position.

The propeller is a low-contrast feature about 3′ across, whose radiant lies just southeast of the cluster’s core. Through my 8-inch reflector, the propeller shows up best when using magnifications ranging from 244x to 300x. I find the two southern blades more apparent than the northern one, owing to the increased contrast of starlight near the core.

Look for the hook of stars to the south of the core and work from there. I find using averted vision, then relaxing my gaze, works best. In other words, while using averted vision, I set my mind at ease by thinking of something pleasant. I do not focus on the stars, but rather let my eyes relax while keeping my mind alert as to where I want to look. By softening my gaze, I become less aware of minute details and more aware of greater shades of contrast. So give the propeller a whirl.

As always, report what you see, or don’t see, to sjomeara31@gmail.com.