Key Takeaways:

- The author recounts observations of Jupiter's Galilean moons using binoculars (8x42 and 10x40/50) and a telephoto lens (200mm EFL 320mm), noting difficulty resolving closely positioned moons, even at apparent separations exceeding a Jupiter diameter.

- Observations highlighted the challenge of resolving closely paired moons, with the author initially mistaking two moons as one single object during a June 10, 2020 observation.

- The author compared his observations to Galileo's early observations of Jupiter's moons, noting that Galileo, too, had difficulty resolving closely positioned moons due to limitations in his instruments.

- The author emphasizes the observational challenges of resolving the Galilean moons, influenced by their relative positions and proximity to Jupiter, even with modern binoculars and despite their brightness.

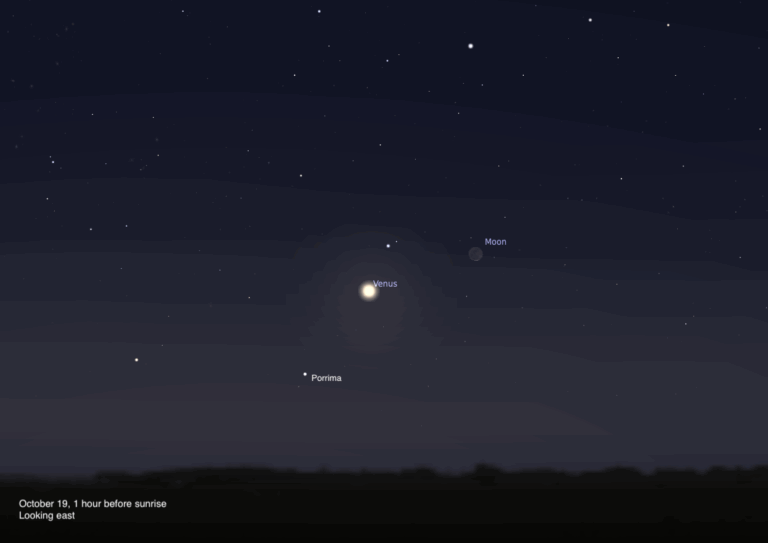

Jupiter is entering our night skies again after sunset — just in time for a project you can undertake in the coming months. All that’s required are a pair of handheld binoculars and some patience.

Before we start, I have to admit that after more than a half century of observing Jupiter, I always took for granted one simple statement: that Jupiter’s four Galilean satellites can be seen through binoculars. While that statement is true in a general sense, I never gave thought to the nuances involved in detecting these moons as their positions shift relative to one another and to their parent planet.

The challenge

The awakening, for me, came the morning of June 10, 2020, when I trained a pair of 8×42 binoculars on Jupiter at 4:21 UT from Maun, Botswana, shortly after the start of astronomical twilight. A waning gibbous Moon was nearby, which also helped illuminate the background sky and cut down on contrast. With a glance, I saw three moons. And had I put down the binoculars, I would have left it at that — assuming that the fourth moon was either behind or in front of the planet, or very close to its edges.

But as I fiddled with the focus, I suddenly saw the moon closest to Jupiter take on an egg-shaped appearance. When I braced the binoculars against the hood of my car, I resolved the “egg” into two close moons.

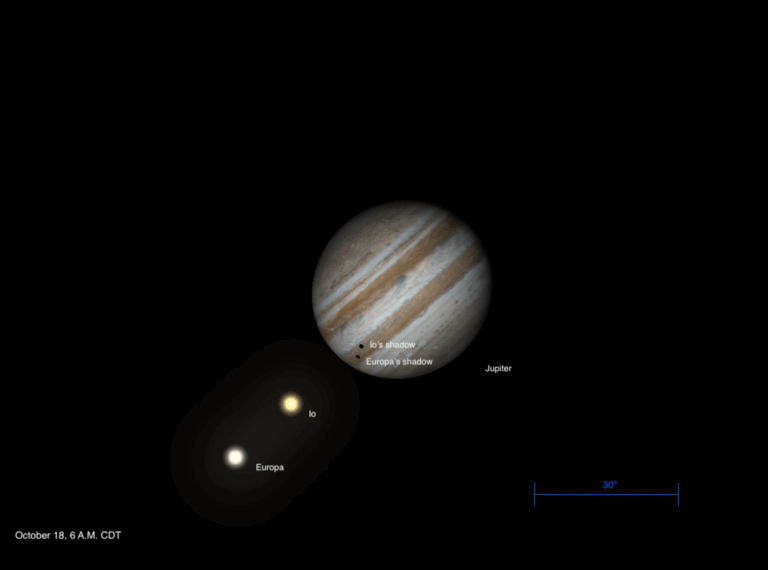

On July 4, 2020 at 18:47 UT, I used the same binoculars to observe Jupiter. This time, a prolonged study revealed two moons, Ganymede and Callisto, on opposite sides of the planet. I then used a telephoto lens to image Jupiter. To my surprise, the image showed another moon (Europa) only about 16″ east of Jupiter’s disk; Io was occulted by the planet.

Try as I might, I could not see Europa through the 8x42s, nor in 10x40s. The moon was, however, just visible through 10x50s, though both stabilized binoculars and patience were required to pull it out from the planet’s glare.

Two weeks later, on July 18 (18:00 UT), three moons were visible (Callisto, Europa, and Ganymede) through 8×42 binoculars. Europa, however, was only seen with difficulty, even though it was roughly one Jupiter diameter (47.5″) to the west of the planet. I found this the most surprising sighting of all, as I had expected that moon to be clearly visible at this apparent separation.

Thoughts on Galileo

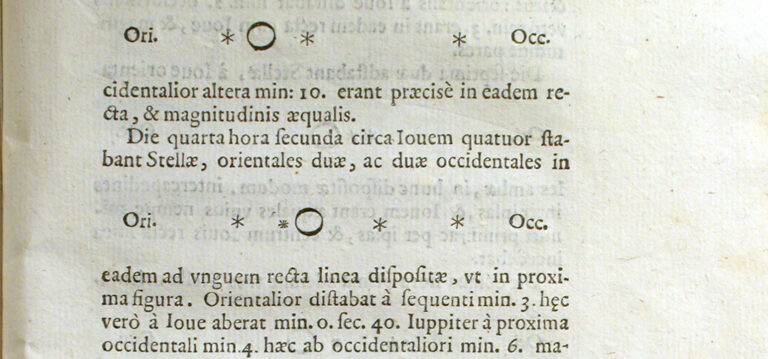

On Jan. 7, 1610, in the first hour after twilight, Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei observed, and drew the positions of, what he believed were three fixed stars near Jupiter. These turned out to be moons — a fact revealed to him over the course of months. Notice, however, that I do not say that “he discovered three of the four Galilean moons.”

Using Fifth Star Labs’ Sky Guide app, I checked the positions of the moons for that date and time against Galileo’s original drawing. I was surprised to find that one of the moons he saw was actually the combined light of Europa and Io, which were passing close to one another during the first hour of nightfall. Had he observed a couple of hours later, the moons would have been further apart and identifiable as four distinct objects.

Similar situations occurred over the course of Galileo’s later observations, where he could not resolve close pairings of moons. But I was impressed by his accurate deduction of the events on the night of Jan. 17, 1610, when, at about 30 minutes after sunset, he saw, initially, only two “stars”:

The easterly star [the combined light of Ganymede and Europa] was distant from … Jupiter by 3′. The westerly [Callisto] by 11′. The easterly seemed twice greater [in brightness] than the other [westerly star]. No more than these two stars were visible. But … on the 5th hour, a third star began to appear which, as I conjecture, was joined with the easterly one and such was their appearance.

A fourth moon (Io) was also visible that night, but Galileo did not resolve it — even though the moon was a little more than a Jupiter-width to the west.