Similarly, we get recommendations to take “hundreds of dark frames” in the hope that we will have a “pure” master dark, the better to create a perfect picture.

Ain’t gonna happen.

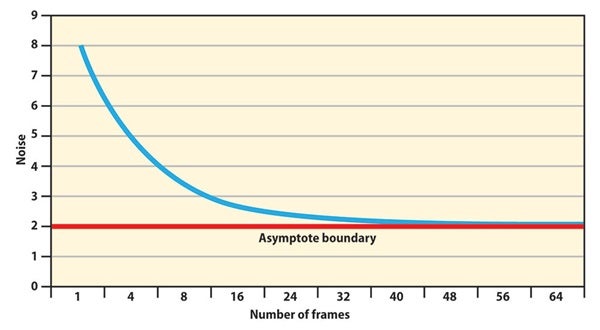

Looking at the graph at left, we notice something interesting. The level of noise does drop dramatically with the averaging of multiple frames at first, but then something strange happens: The curve begins to level out. Specifically, the improvement is substantial up to 16 frames, but after 25 frames, the improvement basically ends.

Related to this is the signal-to-noise formula: The improvement of signal to noise equals the square root of the number of frames combined. Four frames will thus double the signal over the noise, 16 frames will have a fourfold increase, and, theoretically, 25 frames will see a fivefold increase. Remember that at 25 frames, we’re getting close to the asymptotic boundary, beyond which noise doesn’t improve. Plus, the difference between four times and five times improvement is slim to begin with. Adding nine more frames accomplishes basically nothing.

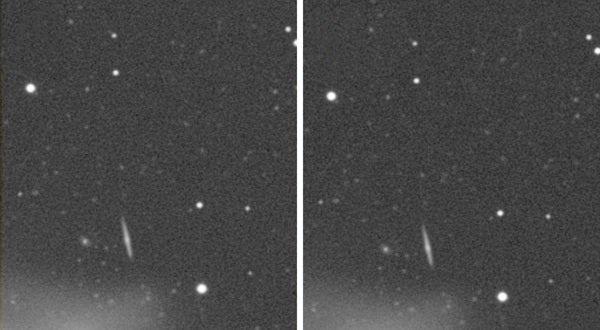

In my experiments, I couldn’t see any improvement after combining nine dark frames. Indeed, comparing the results of a three-frame dark and a 40-frame dark revealed no visible difference when I combined the light frames as a mean (average). See the photo comparison at right for a visual reference.

Remember, you can’t take infinite frames. Make each one count, so that when you combine them to reduce noise, you bring as much as you can to the table. It is thus better to take the longest exposures that your equipment and sky will allow.

After image processing, use noise-reduction software on what noise remains to create the illusion of infinite data. That’s how to get a real-life happy ending.