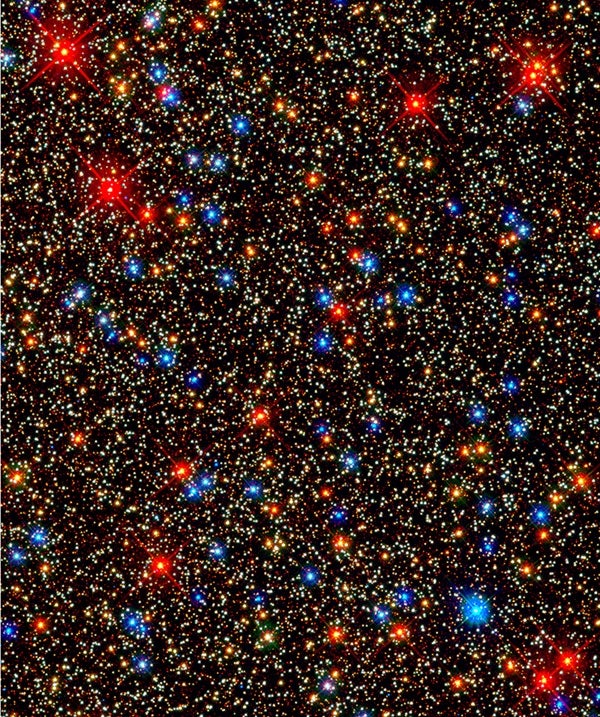

The sight of countless brilliant stars in an inky black skyexhilarates the human spirit, for reasons no one can explain. Such intensity reaches its epitome in a crowded star cluster — and the best of these are the “globulars.”

Some 150 known globular clusters surround the center of the Milky Way. The stars within them not only array in a spherical formation, but they also whiz around the cluster’s center in random elliptical orbits. Adding a final layer to this motif, the globulars themselves form a vast ball-shaped pattern around our galactic core like lights on a spherical crystal chandelier — meaning they ignore the Milky Way’s busy flat plane, which is home to its spiral arms and virtually everything else. Instead, the globular clusters arrange themselves in the “galactic halo,” visibly defining it. If we looked at them alone, we’d conclude our galaxy is not a pancake but a ball. Its structure is wheels-within-wheels, or rather globes-within-globes, since each globular cluster’s component stars are perfect balls of nuclear fire.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

All this is a slightly long-winded way of noting that globulars are strong candidates for the most beautiful objects in the universe. Unlike the tens of thousands of open clusters, whose mostly young blue members congregate far more loosely, the stars in globular clusters are tightly packed, held firmly in the mutual gravitational grip of the collective. Their random individual speeds are insufficient to allow them any chance to escape. They are members forever. Moreover, virtually all globulars consist of ancient stars that date from within a half-billion years of the Big Bang itself. All the stars they hold formed at the same time.

As fascinating as these stunning star clusters are, however, only a single specimen makes it onto our list of the weird: Omega Centauri.

Its moniker hints at its uniqueness. “Omega” is a star name, bestowed more than 400 years ago when Johann Bayer assigned Greek letters to the members of the constellation Centaurus the Centaur. This was pre-telescope, demonstrating that Omega Centauri is easily visible to the naked eye. Indeed, Ptolemy listed it some 2,000 years ago. When Edmond Halley of later comet fame first found it in 1677, it appeared fuzzy in his telescope, so he cataloged it as a nebula.

More than another century passed before John Herschel saw that it was composed not of gas but exclusively of stars — lots of them. Despite its position in Centaurus in the southern sky, forever out of view by those in Europe, it attracted growing attention by astronomers who sailed south, its reputation becoming almost mythical — this was the brightest and richest globular cluster in all the heavens, and the largest, as well. (Later astronomers would discover only a single larger specimen, but not in our galaxy. It lurks instead in Andromeda — a twin named Mayall II.) Omega Centauri seems so different from every other Milky Way star cluster that astronomers wondered if perhaps it did not belong here. Maybe it is an intruder, albeit a handsome one.

Its résumé can be stated quickly. Omega floats at a distance of 15,800 light-years from Earth. Its members are not homogeneous like those of other clusters, but are instead varied and were clearly born at different times. And its stars are oddly legion: While a typical globular cluster has 100,000 to 700,000 members, Omega is off the scale at 5 million. It is so large, in fact, that observers see Omega Centauri as a blob the size of the Moon.

In its center, suns crowd so closely together that they sit just 1/10 of a light-year apart, or only about 6,000 Earth-Sun spans from each other. And while other star clusters have no cohesive spin, Omega rotates, its fastest stars moving at 13 miles (21 kilometers) per second. Why should this sole star cluster be unique? The object of intense study the past 45 years, Omega has appeared more, not less, singular with each new set of data.

Perhaps the most extensive work was done in 1999 by a Korean team of astronomers who obsessively studied 50,000 of Omega’s individual stars. They found that, unlike every other globular, this one indeed possesses multiple population groups. Its stars show a spectrum of metalicities (elements heavier than helium) that indicate formations spanning billions of years, not all at once — almost as if it were a … galaxy! That lead to a single logical conclusion: Omega Centauri is all that remains of a galaxy that our Milky Way captured and cannibalized.

Drawn in, merged, assimilated, and broken apart, that unnamed, now-deceased galaxy has left only a single calling-card of its former existence — its nucleus. This alone stayed preserved against the Milky Way’s tidal destruction because it was glued and bonded forever by the fierce gravitational epoxy of its tightly huddled core members.

So Omega Centauri is more than just huge and gorgeous. It actually came from somewhere else.