Location, location, location. Most regions of our vast trackless universe look like most others, but some places stand out with a vengeance. One unique galaxy occupies just such a privileged position.

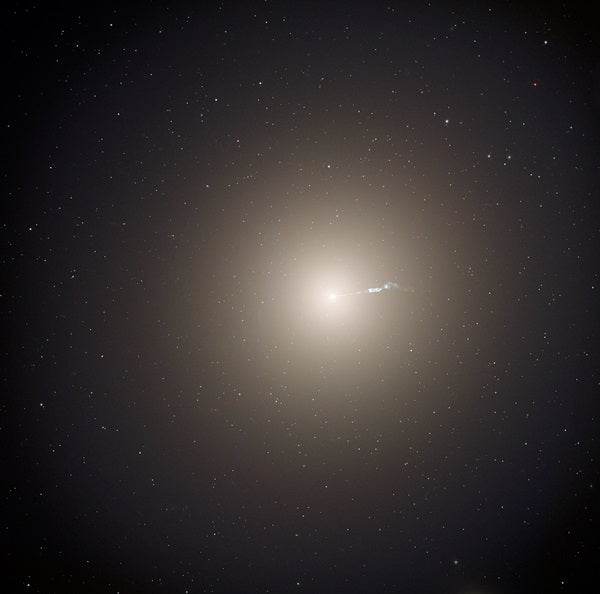

Our Milky Way is one of 5,000 members of the Virgo Supercluster, whose center, 50 million light-years away, is marked by the most massive galaxy in this section of the cosmos, M87. This spherical city of suns is home to several trillion stars (that’s thousands of billions), which means it’s 10 times more populated than our galaxy. Unseen matter seems to make its true mass closer to 200 Milky Ways.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

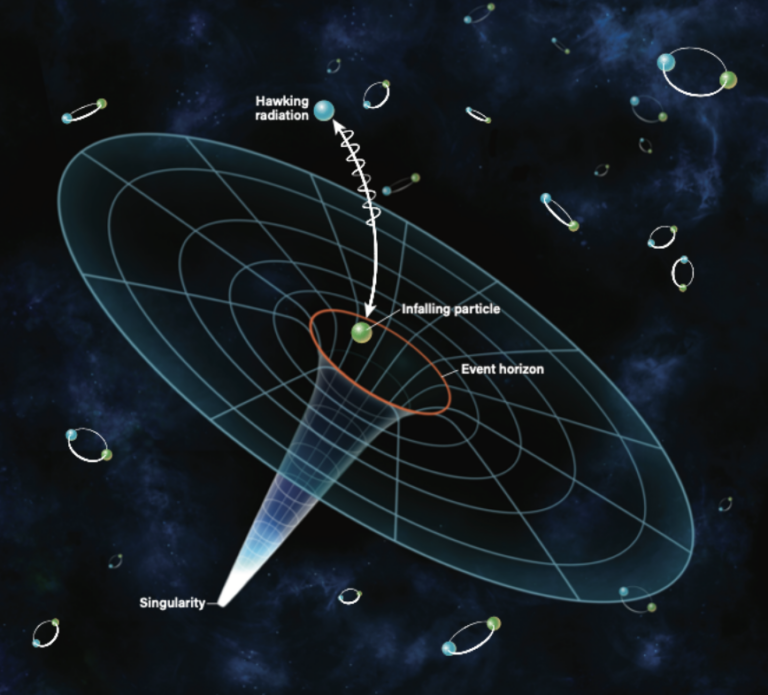

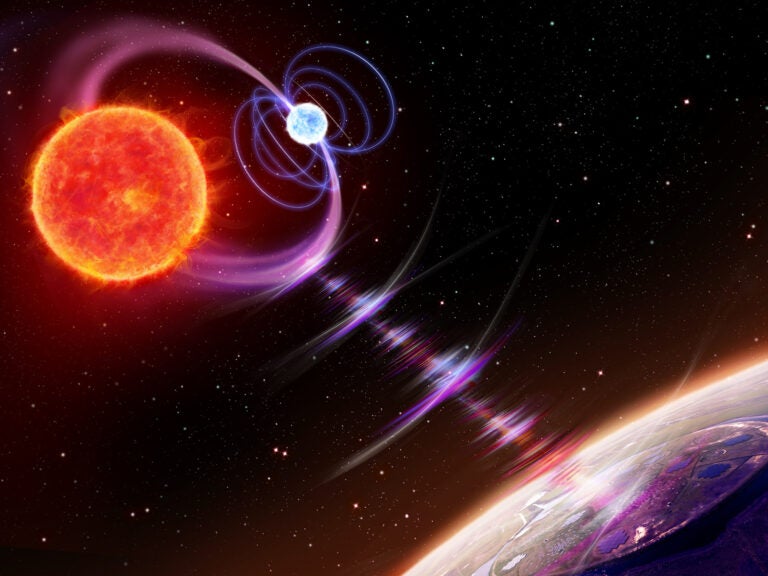

Sitting heavily in its center like Jabba the Hutt is the one of the most massive black holes in the known universe, weighing 6 billion solar masses. And in the very center of that is … well, no one knows. Our science fails under such conditions. All we know is that as we unwrap each box and find another inside, the very sanctum sanctorum is an off-the-scale black hole that shoots a bizarre blue jet of material off its west side almost straight toward us. Moreover, that stuff seems to be traveling far faster than the speed of light.

Let’s rewind back to March 1781, the same month William Herschel discovered Uranus. French astronomer Charles Messier found several blobby-looking objects in the constellation Virgo the Virgin and quickly added them to his catalog. He called one of these number 87, forever after called Messier 87 or M87.

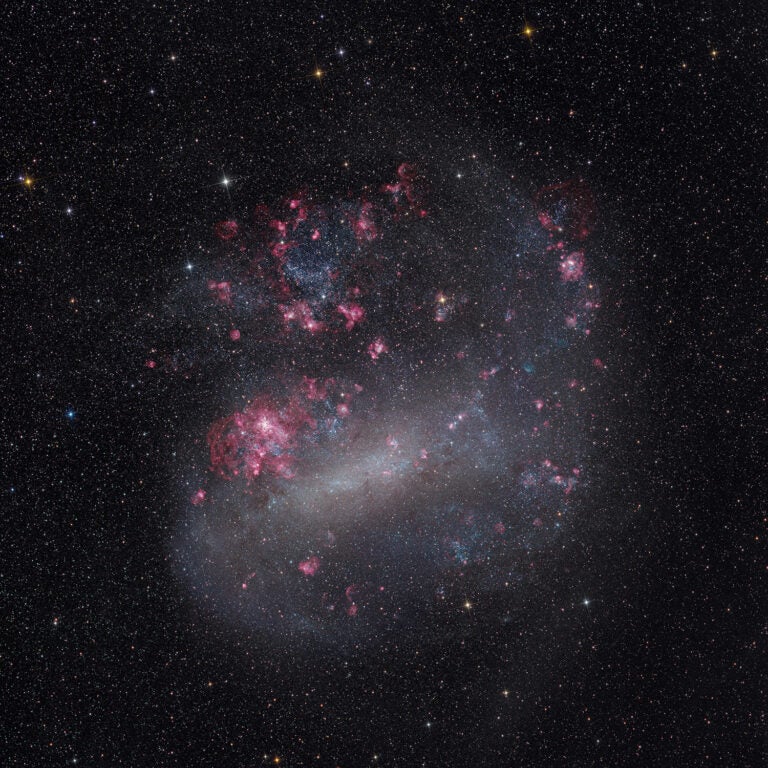

No one learned much else about this fuzzy ball for several lifetimes, until the 20th century, when Heber Curtis discovered the strange jet in 1918. The 1950s brought bigger leaps in our understanding as the new 200-inch Hale Telescope on California’s Palomar Mountain detected an astounding cloud of globular clusters accompanying M87 like a swarm of bees. While our Milky Way has around 150 globulars, M87 is surrounded by some 12,000 of these dense, spherical star cities. Each is almost an island universe of its own, adding yet another onion layer to this monster galaxy.

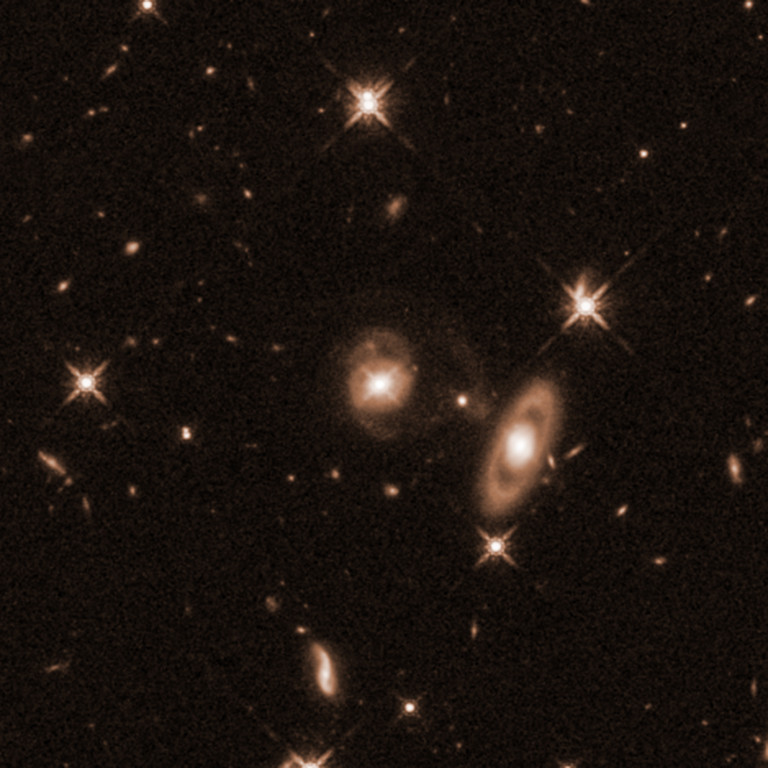

At around this time, M87’s true distance of 55 to 60 million light-years became apparent, letting us pin its diameter at 120,000 light-years, which is similar to the size of our galaxy. Except that M87’s far greater density, and the fact that its 2.7 trillion members form a voluminous ball rather than a disk, puts it out of our population league. Recent photos show fainter outer layers that extend much farther, making its true size in our sky more like ½°, the same as the Full Moon. This forced a major recent revision of its width to 500,000 light-years. And just this year, studies reveal that M87 likely swallowed an entire other galaxy in the last billion years.

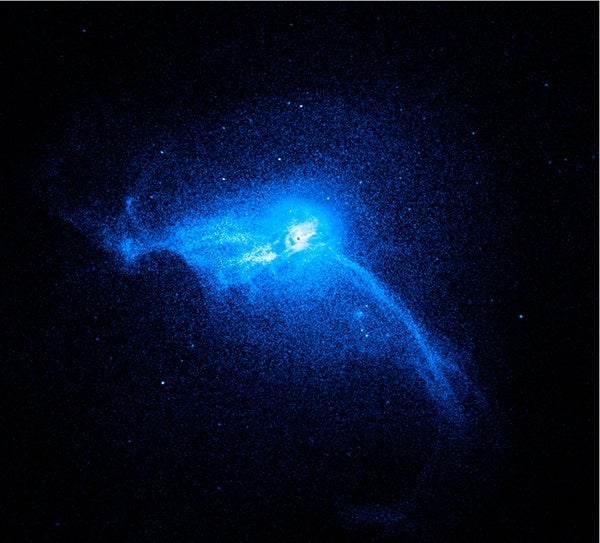

In 1954, M87 was identified as the visual object corresponding to an intense point-like source of celestial radio noise found in 1947, named Virgo A. Later, in 1965 and 1967, when rocket-borne X-ray detectors became available, observers saw M87 as a powerful source of those emissions as well, whose filaments extend far beyond the visible jet for an amazing 100,000 light-years. Messier 87 also creates extremely strong gamma-ray emissions, the most powerful electromagnetic energy of all.

Naturally, when the Hubble Space Telescope launched, M87 became a prime focus of its investigations — especially that odd jet shooting westward from its center, which Hubble showed to be violently roiling and boiling. A second, much smaller jet also was discovered emanating from the exact opposite side of the galaxy’s supermassive black hole. A knot in the main jet, named HST-1, periodically monitored by the Hubble Space Telescope and the Chandra X-ray Observatory, has over a relatively recent four-year period mysteriously grown 50 times brighter.

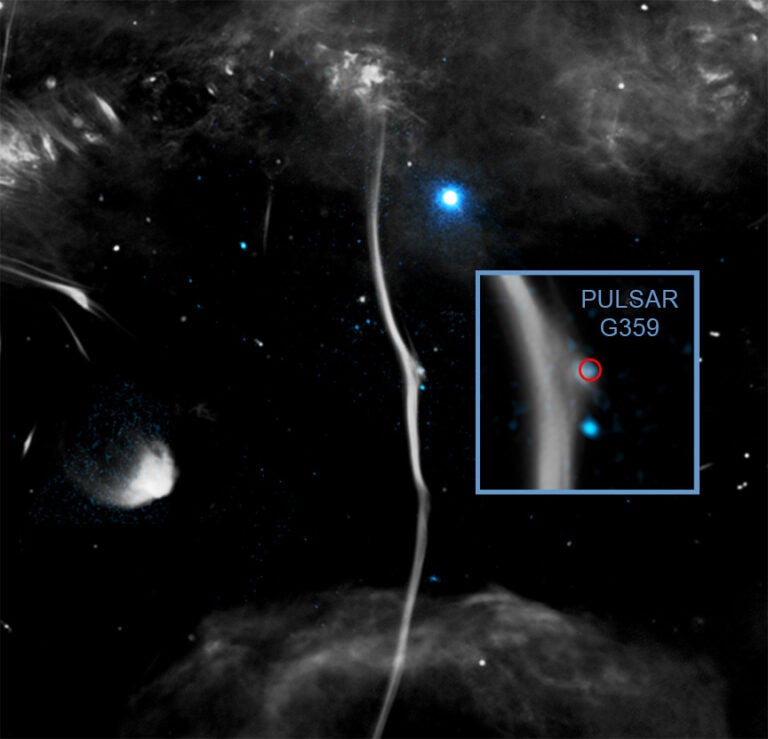

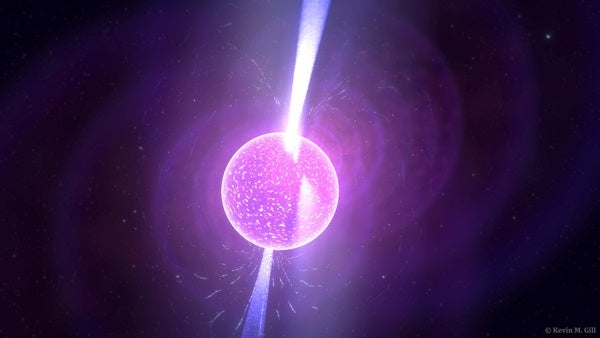

This jet is the source of all those intense X-rays, gamma rays, and radio waves. The jet has a deep blue color that comes from synchrotron radiation, produced by electrons in super-strong magnetic fields. It’s generated by material falling into M87’s award-winning black hole. Synchrotron emissions are a very rare kind of glow, a sign of ultra-extreme conditions, and are seen in only a few other celestial objects like the Crab Nebula. The visible 5,000 light-year-long jet seems to race outward at five times the speed of light. Because we know this is impossible, we assume it’s a perspective effect, an illusion caused by the beam being highly foreshortened because it’s heading almost straight in our direction. Through backyard amateur telescopes, M87 is easily visible; at magnitude 9.6, it holds little challenge. But the jet requires unspoiled skies and a large aperture.

Unlike Omega Centauri or the Tarantula Nebula, M87 is not calendar material. Few would find it beautiful. Its appeal is for the mind alone. For here in Virgo, we observe the most massive galaxy in our quadrant of the cosmos, housing a record-setting black hole that explosively creates a strange violent blue jet whose workings remain a frustrating mystery.