Despite their discovery less than 50 years ago, neutron stars don’t get much attention now. They’re neither as notorious as black holes nor as capable of fully warping space-time. The media shy away from runner-ups and wannabes. That’s a shame because it’s like ignoring a talking gorilla sitting next to you at the movies just because a flying saucer is in the parking lot.

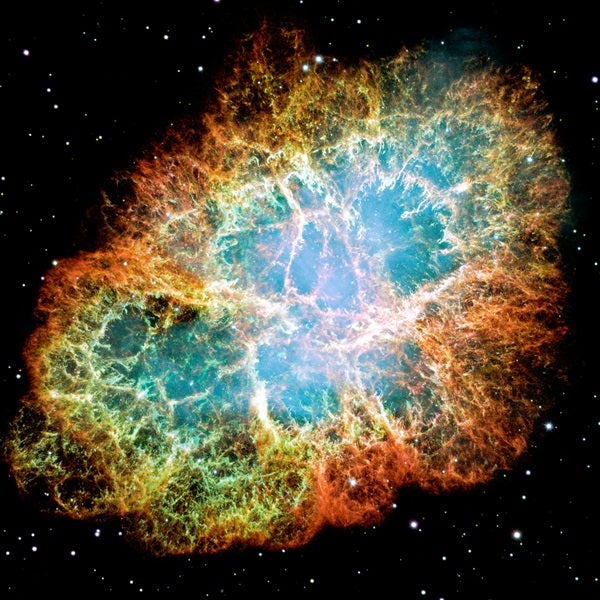

The story of the Crab Nebula (M1) really started before dawn July 4, 1054, when a dazzling new star abruptly appeared near the left horn of Taurus the Bull. As bright as Venus, it could be seen in broad daylight for weeks. It was duly noted by observers in China and duly ignored in the West, where alterations in the heavens were hard to reconcile with the prevailing theology.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

Centuries later, our telescopes revealed this object as the remnant of an exploded star 6,500 light-years away, whose tendrils still rush outward at 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) a second, visibly altering the nebula every few years.

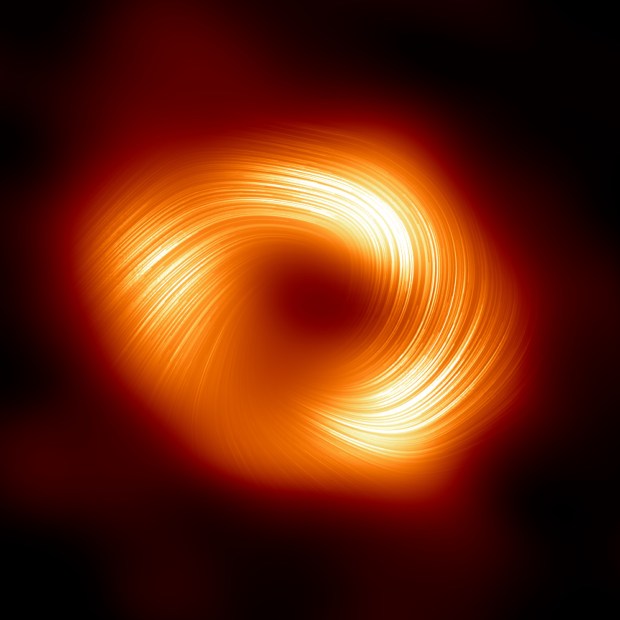

If it’s weirdness you want, consider that the Crab Nebula’s bizarre glow is neither starlight, nor reflected light, nor excited gas. Its origin is neither heat nor nuclear energy. Instead, its central glow results from an exotic phenomenon called synchrotron radiation, produced when electrons are forced to change direction by super-powerful magnetic fields. Don’t picture the kind of magnetism that wobbles a compass needle. The field near the Crab is a trillion times stronger than Earth’s. It would rip that compass right out of your hand. It blasts electrons into violent spiraling geysers that produce bits of eerie blue light like yelps of protest.

But this strange lavender glow is just the cloak, the picture frame that surrounds the inner sanctum of strangeness. Now we get to the object that sits heavily at the heart of the nebula and creates the magnetic field and forbidden radiation: the Crab Pulsar.

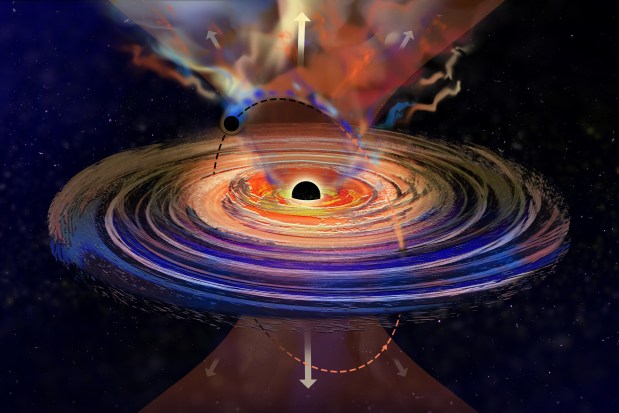

At first, “pulsar” seems simple enough. It’s a tiny solid neutron star whose magnetic poles sweep past our line of sight with each rotation. Like a lighthouse, it delivers a quick burst of energy at all wavelengths with every turn. The Crab Pulsar, with roughly our Sun’s mass, is the remnant of what used to be the original giant star’s core. When the rest of the star went kablooey and exploded outward, this tiny remnant went the other way and collapsed inward. As it spins 33 times a second, its light looks visually steady because nobody can differentiate more than 20 flashes per second, the human flicker-fusion threshold. It’s more rapid than the frames of a movie projector.

The Crab’s intense magnetic field acts as a drag, a brake, and slows the wildly spinning star while-U-wait. Eventually, the Crab Pulsar will whirl “just” 17 times a second — with a flickering finally noticeable through amateur telescopes — by the year 4000.

Imagine watching that unfortunate sun blow itself to Kingdom Come. The shattered star’s core dramatically deflated like a punctured balloon, the material of a half-million planet Earths packing itself briskly into a ball smaller than Brooklyn, New York. Laws of physics that normally keep objects apart but fail in places like supernovae and subway cars allowed this sun to collapse to a radius of only 8 miles (13 km).

As it shrank, ever-strengthening gravity imploded the star’s atomic contents and fused them into a compressed swarm of neutrons, with some packed leftover protons and electrons elbowing each other in vain for a little breathing room. “Dense” or “hard” are pathetic understatements; the density of Crab Pulsar material is the same as a sugar cube containing the steel in every American automobile combined. We could duplicate the star’s density if we could crush a cruise ship down to the size of the ball in a ballpoint pen. Except, in this case, the Crab Pulsar isn’t merely a tiny speck of the stuff, but a sphere 16 miles (26 km) across containing nothing but. Interestingly enough, this is the same density of every atomic nucleus in your body. So, in a way, the Crab Pulsar is one huge neutron, roughly 1/200 the width of the Moon.

We usually think of star surfaces as gassy and unsupportive. The Sun’s vaporous visible photosphere is less dense than water. But unimaginable gravity has forced the Crab Pulsar’s broken atom fragments into a kind of lattice, its exterior skin a spherical glass-like structure with a hundred thousand trillion times the stiffness of steel. It doesn’t need to be insured. You couldn’t damage it, or even scratch it, with a hydrogen bomb.

A half-mile beneath this impenetrable crust, the star turns liquidy yet gets even denser. Nonetheless, this fluid boasts a curious super-slipperiness that lets the star’s interior effortlessly spin at a different rate than its surface. And at the center, a few miles down, we find a total mystery as our present science breaks down completely.