Key Takeaways:

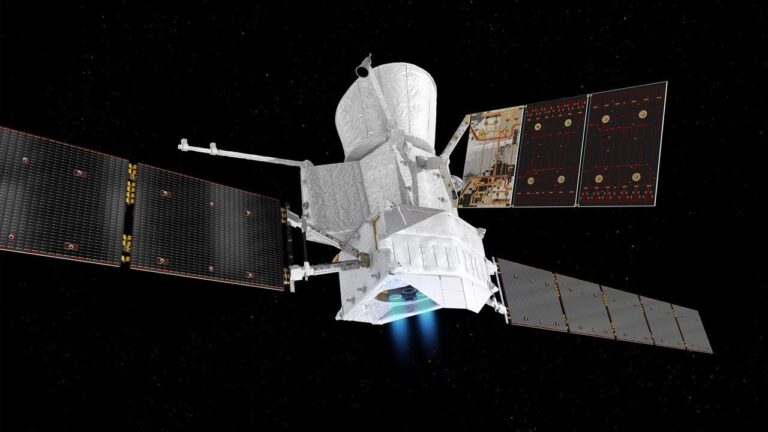

Some people love their cars so much they just keep driving the old junkers for years and years, racking the mileage up to hundreds of thousands of miles before finally having them towed to the junk yard. NASA and planetary scientists have been so fond of the Galileo spacecraft that they’ve extended the mission far beyond its original length and pushed the aged spacecraft’s odometer to a whopping 2,878,053,500 miles (4,631,778,000 kilometers) before sending it to its demise in Jupiter’s cloud tops this Sunday.

At 2:57 p.m. EDT on September 21, the Galileo spacecraft will intentionally crash into Jupiter at nearly 108,000 miles per hour (48.2 kilometers per second). As Galileo plunges into the gas giant just south of its equator, friction from the jovian atmosphere will cause the spacecraft to break apart. The pieces of Galileo will not make it far into Jupiter’s depths before they are vaporized.

Galileo’s dramatic destruction has been orchestrated to avoid a potential collision with Jupiter’s moon, Europa, which may have a subsurface ocean that could harbor life. After almost 14 years in space, Galileo is running low on propellant, and once that’s gone, the mission team will no longer be able to control the spacecraft.

The suicide dive will mark the end of a successful career that lasted much longer than expected and outlived several team members, despite the failed deployment of Galileo’s main antenna, a flaky tape recorder, and a debilitating, cumulative radiation exposure four times greater than the spacecraft was designed to endure.

“We had a lot of problems,” former Galileo project manager Jim Ericksson said while reflecting on the mission last week. “But we overcame them.”

The Jupiter Orbiter Probe mission was originally devised in 1977 and scheduled for launch in 1982. After several delays, the renamed Galileo spacecraft finally reached space aboard the Space Shuttle Atlantis in October 1989. A Venus flyby and two Earth passes got the spacecraft up to speed for its six-year journey to Jupiter. On the way, Galileo captured the first-ever close-up images of an asteroid when it flew past Gaspra in 1991, it discovered the first-known asteroid moon when it encountered Ida in 1993, and it observed the collision of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 with Jupiter in 1994 from an angle we couldn’t see from Earth.

As it arrived at Jupiter in 1995, Galileo released a probe into the planet’s atmosphere that survived for 58 minutes, studying the jovian clouds, winds, and composition before it was vaporized about 100 miles below the cloud tops.

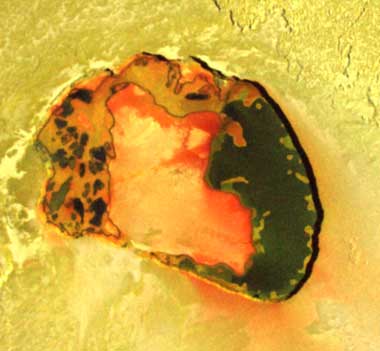

After situating itself around Jupiter in December 1995, Galileo spent the next several years and 34 orbits studying the giant planet, its rings and magnetosphere, and the Galilean moons. It witnessed thunderstorms and lightning much more powerful than Earth’s. It watched Io’s surface ooze, erupt, and transform in volcanic feats unmatched on our world. It discovered a magnetic field around Ganymede (the first known around a moon). It imaged ice rafts on Europa and found that Callisto had no metallic core like the three other large moons. Galileo’s also found several indications of liquid oceans beneath the surfaces of Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

Originally planned for a two-year tour of the jovian system, the mission was extended three times. In total, it returned 30 gigabytes of data, including roughly 14,000 pictures, to Earth.

“It has been a fabulous mission for planetary science, and it is hard to see it come to an end,” shares Galileo project manager Claudia Alexander. But like an auto lover who’s trying to drive that final mile before his car sputters to a stop, the Galileo team is going to leave the spacecraft’s fields and particles instruments, radio science instrument, and magnetometer all on during the fated fall to see whether they can extend the mission just a little more. “We’re keeping our fingers crossed that, even in its final hour, Galileo will still give us new information about Jupiter’s environment,” Alexander says.

If you’d like to share in Galileo’s last hours, you can view an end of mission webcast from 2 to 3 p.m. EDT on Sunday or an end of mission celebration on NASA TV from 3 to 4 p.m. EDT.

Update: The Galileo mission has ended. The Deep Space Network tracking station in Goldstone, California, received Galileo’s last signal at 3:43:14 EDT. (The signal arrived after Galileo’s destruction due to the time it took for it to reach Earth.)