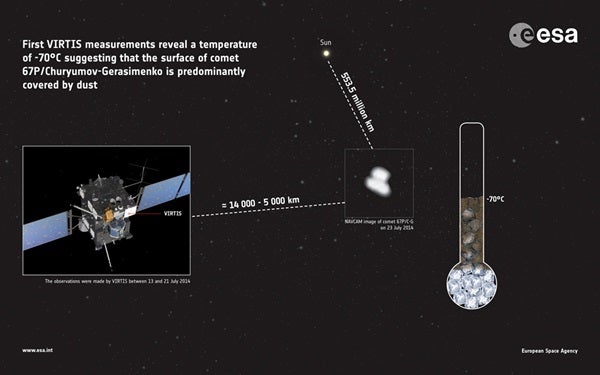

The observations of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko were made by Rosetta’s visible, infrared, and thermal imaging spectrometer, VIRTIS, between July 13 and 21 when Rosetta closed in from 8,700 miles (14,000 kilometers) to the comet to just over 3,100 miles (5,000km).

At these distances, the comet covered only a few pixels in the field of view, so it was not possible to determine the temperatures of individual features. But, using the sensor to collect infrared light emitted by the whole comet, scientists determined that its average surface temperature is about –94° Fahrenheit (–70° Celsius).

The comet was roughly 345 million miles (555 million km) from the Sun at the time — more than three times farther away than Earth — meaning that sunlight is only about a tenth as bright.

Although –94° F (–70° C) may seem rather cold, it is some 35–55° F (20–30° C) warmer than predicted for a comet at that distance covered exclusively in ice.

“This result is very interesting since it gives us the first clues on the composition and physical properties of the comet’s surface,” said Fabrizio Capaccioni from INAF-IAPS in Rome.

Indeed, other comets such as 1P/Halley are known to have very dark surfaces owing to a covering of dust, and Rosetta’s comet was already known to have a low reflectance from ground-based observations, excluding an entirely “clean” icy surface.

The temperature measurements provide direct confirmation that much of the surface must be dusty because darker material heats up and emits heat more readily than ice when it is exposed to sunlight.

“This doesn’t exclude the presence of patches of relatively clean ice, however, and very soon VIRTIS will be able to start generating maps showing the temperature of individual features,” said Capaccioni.

In addition to global measurements, the sensor will study the variation of the daily surface temperature of specific areas of the comet in order to understand how quickly the surface reacts to solar illumination.

In turn, this will provide insight into the thermal conductivity, density, and porosity of the top tens of centimeters of the surface. This information will be important in selecting a target site for Rosetta’s lander, Philae.

It also will measure the changes in temperature as the comet flies closer to the Sun along its orbit, providing substantially more heating of the surface.

“Combined with observations from the other 10 science experiments on Rosetta and those on the lander, VIRTIS will provide a thorough description of the surface physical properties and the gases in the comet’s coma, watching as conditions change on a daily basis and as the comet loops around the Sun over the course of the next year,” said Matt Taylor from ESA.