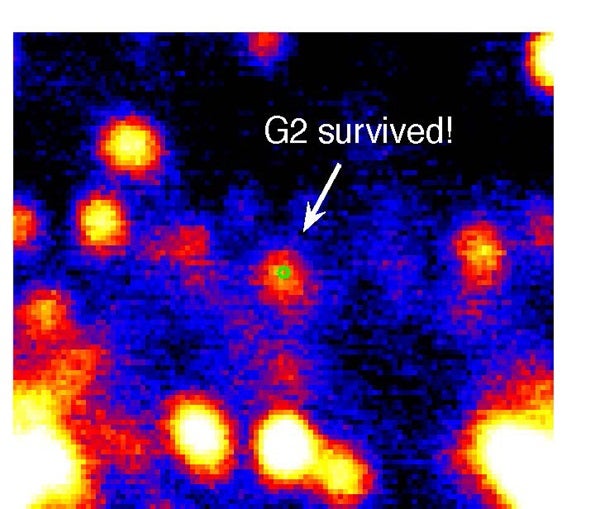

While some scientists believed the object was a cloud of hydrogen gas that would be torn apart in a fiery show, Andrea Ghez from UCLA and her team proved it was much more interesting.

“G2 survived and continues happily on its orbit; a gas cloud would not do that,” said Ghez. “G2 was completely unaffected by the black hole; no fireworks.”

Instead, the team has demonstrated it is a pair of binary stars that had been orbiting the black hole in tandem and merged together into an extremely large star, cloaked in gas and dust, and choreographed by the black hole’s powerful gravitational field.

“G2 is not alone,” said Ghez. “We’re seeing a new class of stars near the black hole and as a consequence of the black hole.”

Ghez and her colleagues Gunther Witzel and Mark Morris, both from UCLA, studied the event with both of the 10-meter telescopes at Keck Observatory.

Keck Observatory employs a powerful technology called adaptive optics, which Ghez helped pioneer, to correct the distorting effects of Earth’s atmosphere in real time and to reveal the region of space around the black hole. With adaptive optics, Ghez and her colleagues have revealed many surprises about the environment’s surrounding supermassive black holes, discovering, for example, young stars where none were expected and seeing a lack of old stars where many were anticipated.

“The Keck Observatory has been the leader in adaptive optics for more than a decade and has enabled us to achieve tremendous progress in correcting the distorting effects of the Earth’s atmosphere using high-angular resolution imaging techniques,” Ghez said.

The researchers wouldn’t have been able to arrive at their conclusions without the Keck’s advanced technology. “It is a result that in its precision was possible only with these incredible tools, the Keck Observatory’s 10-meter telescopes,” Witzel said.

“We are seeing phenomena about black holes that you can’t watch anywhere else in the universe,” Ghez added. “We are starting to understand the physics of black holes in a way that has never been possible before and is possible only at the center of the galaxy.”

Massive stars in our galaxy, she noted, primarily come in pairs. When the two stars merge into one, the star expands for more than 1,000,000 years “before it settles back down,” Ghez said. “This may be happening more than we thought; the stars at the center of the galaxy are massive and mostly binaries. It’s possible that many of the stars we’ve been watching and not understanding may be the end product of a merger that are calm now.”

G2, in that explosive stage now, has been an object of fascination. “Its closest approach to the black hole was one of the most watched events in astronomy in my career,” Ghez said.

G2 makes an unusual 300-year elliptical orbit around the black hole, and Ghez’s group calculated its closest approach occurred this summer — later than other astronomers believed — and they were in place at Keck Observatory to gather the data.

Black holes, which form out of the collapse of matter, have such high density that nothing can escape their gravitational pull, not even light. They cannot be seen directly, but their influence on nearby stars is visible and provides a signature, said Ghez.