Key Takeaways:

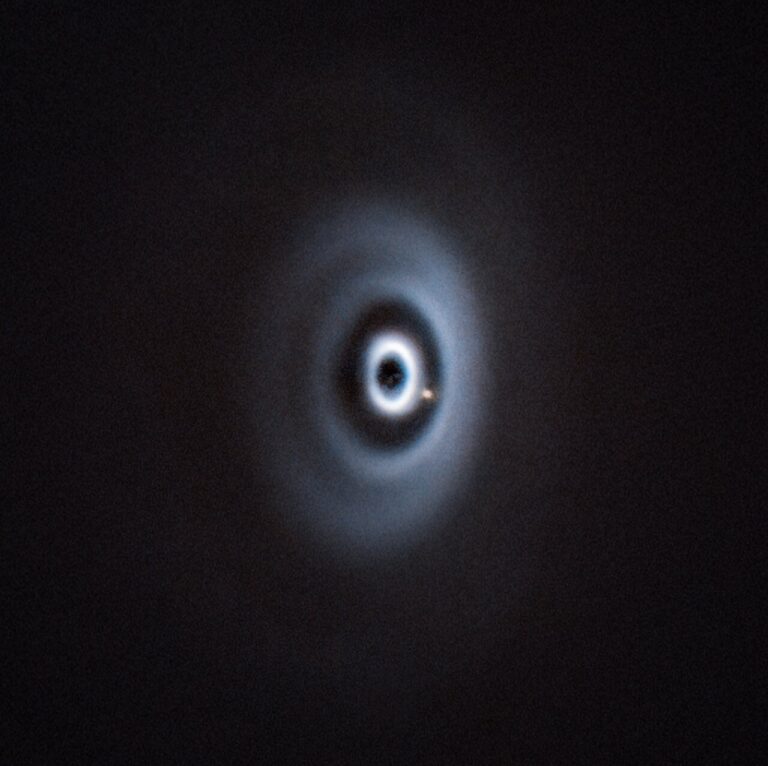

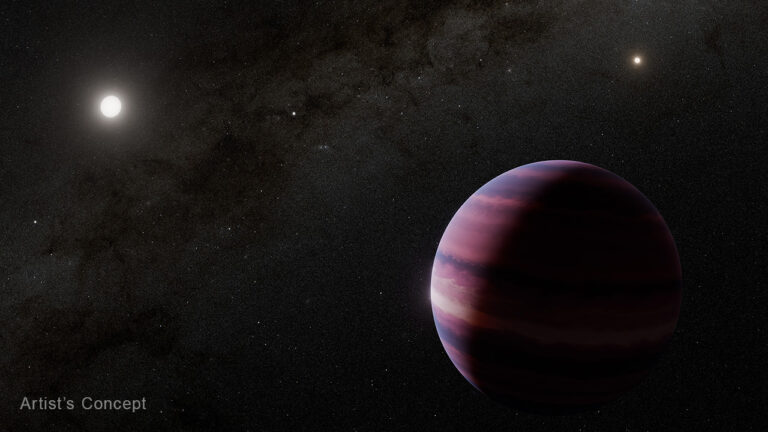

- A new four-star planetary system, 30 Ari, located 136 light-years away in the constellation Aries, has been discovered using adaptive optics technologies at Palomar Observatory.

- The system contains a Jupiter-mass planet (10 times the mass of Jupiter) orbiting its primary star with a period of 335 days.

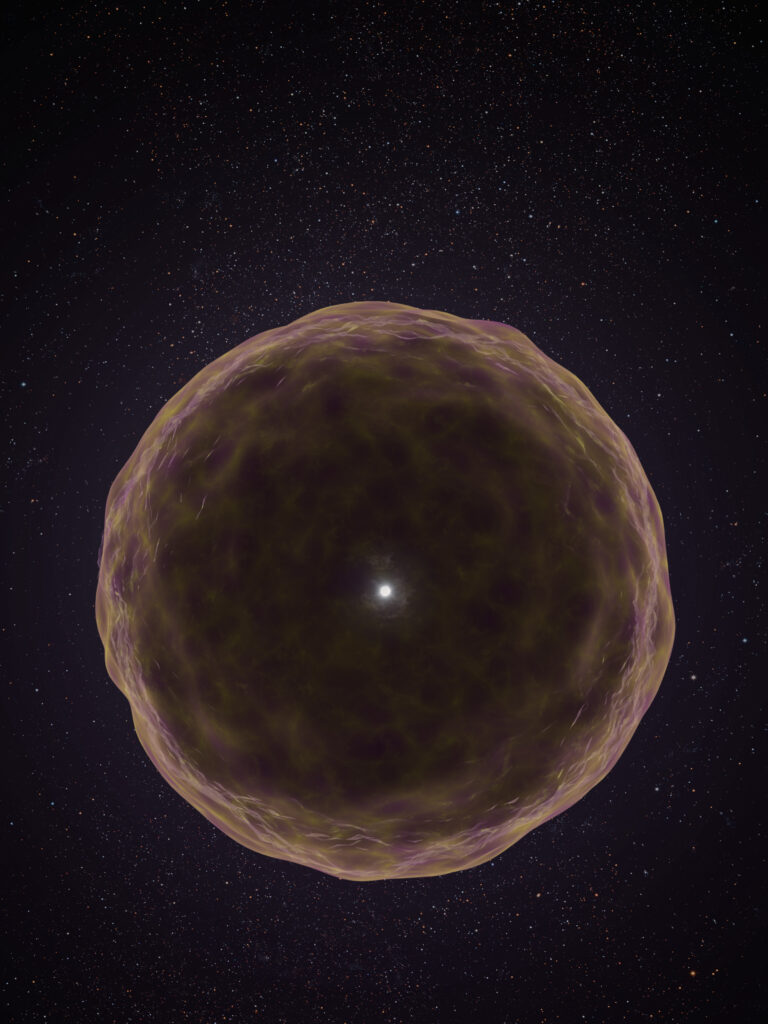

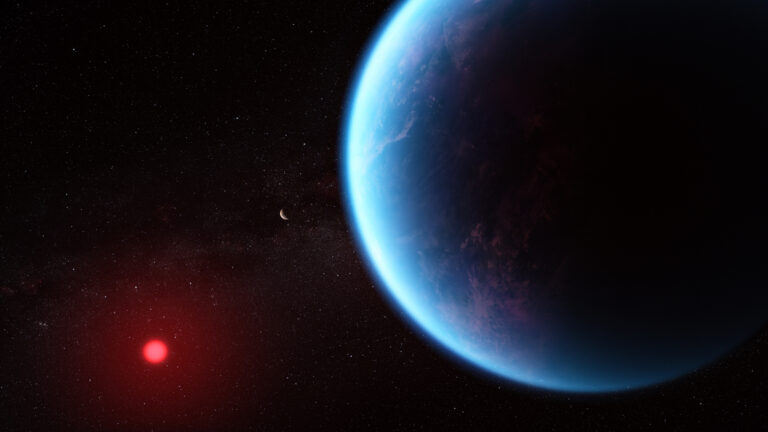

- The discovery of a fourth star, a red dwarf, increases the known stellar components of 30 Ari from three to four, suggesting that planets in quadruple star systems may be more common than previously thought.

- The newly discovered star's distance from the planet (23 times the Sun-Earth distance) appears to have not significantly impacted the planet's orbit, although further observation is planned to clarify this.

The discovery was made at Palomar Observatory using two new adaptive optics technologies that compensate for the blurring effects of Earth’s atmosphere: the robotic Robo-AO adaptive optics system developed under the leadership of Christoph Baranec of the University of Hawaii at Manoa’s Institute for Astronomy and the PALM-3000 extreme adaptive optics system developed by a team at Caltech and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) that also included Baranec.

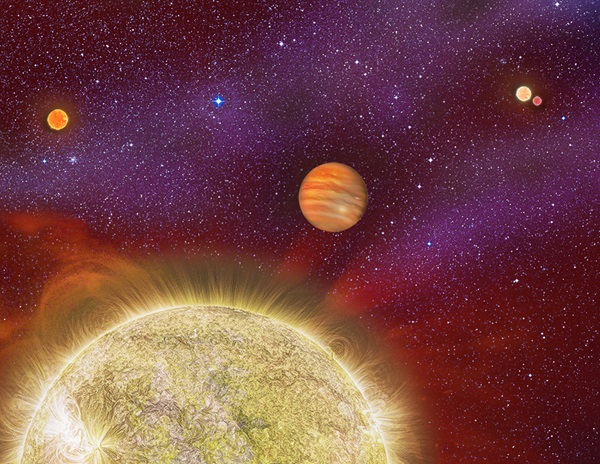

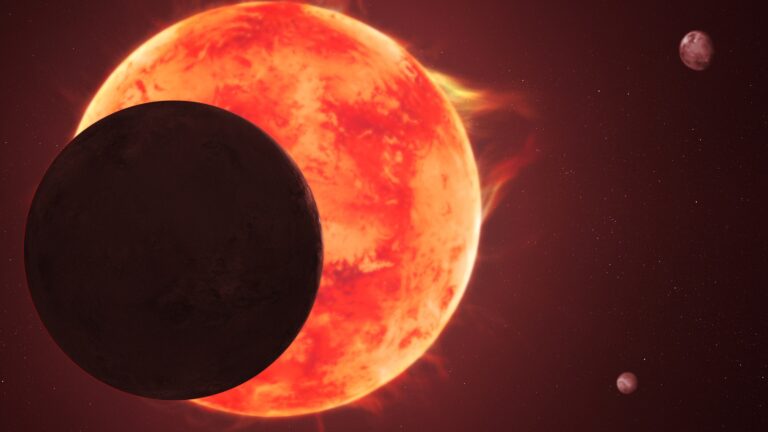

The newfound four-star planetary system, called 30 Ari, is located 136 light-years away in the constellation Aries. The system’s gaseous planet is enormous, with 10 times the mass of Jupiter, and orbits its primary star every 335 days.

The new study brings the number of known stars in the 30 Ari system from three to four. This discovery suggests that planets in quadruple star systems might be less rare than once thought.

“About 4 percent of solar-type stars are in quadruple systems, which is up from previous estimates because observational techniques are steadily improving,” said Andrei Tokovinin of the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile.

The newly discovered fourth star, whose distance from the planet is 23 times the Sun-Earth distance, does not appear to have impacted the orbit of the planet. The exact reason for this is uncertain, so the team is planning further observations to better understand the orbit of the newly discovered star and its complicated family dynamics.

Were it possible to see the skies from this world, the four stars would look like one small Sun and two very bright stars that would be visible in daylight. If viewed with a large enough telescope, one would see that one of those bright stars is actually a binary system — two stars orbiting each other.

In recent years, dozens of planetary systems with two or three host stars have been found, including those that would have twin sunsets reminiscent of the ones on the fictional Star Wars planet Tatooine. Finding planets with multiple stars isn’t too much of a surprise considering binary stars are more common in our galaxy than single stars such as our Sun.

Lead author Lewis Roberts from JPL and his colleagues want to understand the effects that multiple stars can have on their developing youthful planets. Evidence suggests that stellar companions can influence the fate of planets by changing the planets’ orbits and even triggering some to grow more massive.

The “hot Jupiter” planets that whip around their stars in just days, for example, might be gently nudged closer to their primary star by the gravitational hand of a stellar companion. “This result strengthens the connection between multiple star systems and massive planets,” said Roberts.

“The discovery of this exciting system is only possible when we quickly scan through large numbers of potential targets,” said Baranec. “At the moment, Robo-AO is the only instrument that can give us the necessary combination of resolution and efficiency. Once we discover something interesting with Robo-AO, we can follow up with the ‘Formula 1′ systems, like PALM-3000 or the SCExAO system at the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii, to obtain the absolute sharpest images possible. Additionally, we’re planning to bring a new, more powerful Robo-AO system to the University of Hawaii 2.2-meter telescope to leverage the pristine skies of Mauna Kea, Hawaii. We’ll use it for even larger surveys and follow-up observations of asteroids and supernovae discovered by ATLAS on Mauna Loa and Haleakala.”

ATLAS (Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System) is an asteroid-impact early-warning system being developed by the University of Hawaii with funding from NASA. When completed in 2015, it will consist of two telescopes, one on Mauna Loa and the other on Haleakala, that will automatically scan the whole visible sky several times every night looking for moving objects.