Key Takeaways:

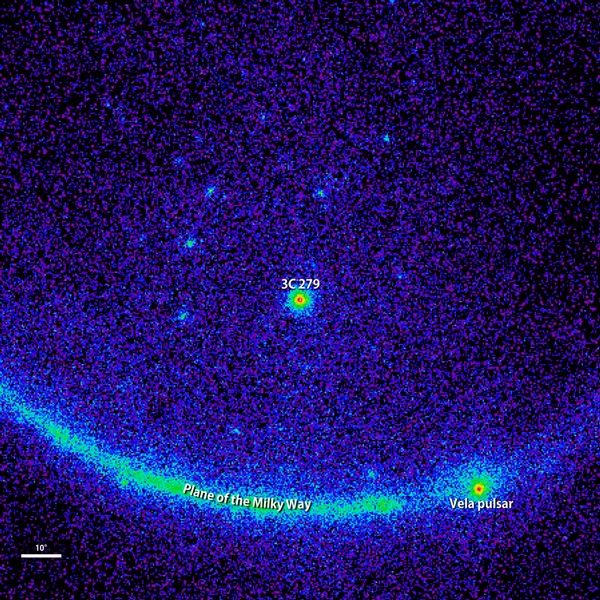

“One day 3C 279 was just one of many active galaxies we see, and the next day it was the brightest thing in the gamma-ray sky,” said Sara Cutini from the Italian Space Agency’s Science Data Center in Rome.

3C 279 is a famous blazar, a galaxy whose high-energy activity is powered by a central supermassive black hole weighing up to a billion times the Sun’s mass and roughly the size of our planetary system. As matter falls toward the black hole, some particles race away at nearly the speed of light along a pair of jets pointed in opposite directions. What makes a blazar so bright is that one of these particle jets happens to be aimed almost straight at us.

“This flare is the most dynamic outburst Fermi has seen in its seven years of operation, becoming 10 times brighter overnight,” said Elizabeth Hays from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. Astronomers think some change within the jet is likely responsible for the flare, but they don’t know what it is.

The brightest persistent source in the gamma-ray sky is the Vela pulsar, which is about 1,000 light-years away. 3C 279 is millions of times farther off, but during this flare it became four times brighter than Vela. This corresponds to a tremendous energy release, and one that cannot be sustained for long. The galaxy dimmed to normal gamma-ray levels by June 18.

The rapid fading is why astronomers rush to collect data as soon as they detect a blazar flare. “Our priority is to make observations while the object is still bright,” said Masaaki Hayashida from the University of Tokyo’s Institute for Cosmic Ray Research. “Once it’s over, we can start trying to understand the mechanisms powering it.”

The Italian Space Agency’s AGILE gamma-ray satellite first reported the flare, followed by Fermi. Rapid follow-up observations were made by NASA’s Swift satellite and the European Space Agency’s INTEGRAL spacecraft, which just happened to be looking in the right direction, along with optical and radio telescopes on the ground.

3C 279 holds a special place in the history of gamma-ray astronomy. During a flare in 1991 detected by the EGRET instrument on NASA’s then recently launched Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, which operated until 2000, the galaxy set the record for the most distant and luminous gamma-ray source known at the time. “Although we didn’t expect to find the galaxy so bright, we soon had a much greater surprise,” said Robert Hartman from Goddaard. “Its brightness varied substantially, becoming four times brighter within 10 days.”

The June 14 outburst rapidly brightened in less than a day and peaked June 16, producing a gamma-ray flare 10 times brighter than the 1991 event. These rapid variations convey information about the size of the emitting region, which cannot be larger than the distance light can travel during the flare.