Exoplanets are now a dime a dozen. Before 1995 it was unknown whether or not other main sequence stars even hosted their own planets, but now we know that, statistically, almost every star in the galaxy is likely to have at least one planet, and many even have multiple.

Thanks to missions like Kepler we now have 3400 confirmed exoplanets and another 5400 waiting to be officially added to the list. Many of these are gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn, some are Neptune like and covered in ice, but there are a few that are rocky like our home.

Of the 3400 confirmed exoplanets, there are only around 15 that fall into the category of ‘habitable’ and out of those 15, there are five that SETI astronomer Jeff Coughlin thinks are the most interesting.

Coughlin talked to us about his guidelines for what’s really considered “habitable” and what’s not. A lot of what makes a planet habitable falls into a few categories: its size, its distance from its host star, and exactly what kind of star it orbits around. What we think of as a habitable world isn’t always the same marker for scientists.

“When the everyday person hears the word habitable they probably think something like Earth or (a place) humans could walk out of a spaceship and be happy: there’s water, an atmosphere, gravity wouldn’t be too high, the temperature wouldn’t be too hot or too cold,” Coughlin explains. “But when astronomers talk about habitable worlds we’re really just asking about two things: could there be liquid water on what is a mostly rocky surface, nothing like Jupiter where you have a huge atmosphere crushing you down-those are really the two terms that astronomers think about. When we say a planet is habitable, that’s all we really mean.”

Let’s take a tour through the top most habitable exoplanets that we know of so far:

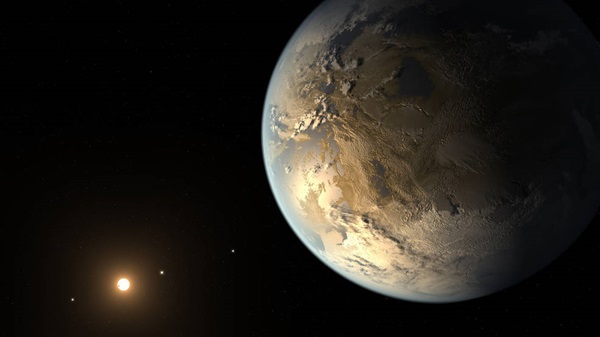

The first on the list is Kepler 186-f.

“This is my personal favorite at the moment. Kepler 186-f was found by the Kepler telescope a couple of years ago. It’s remarkable because it was the first one that was really similar in size to Earth and is in the goldilocks zone where water can exist.” Kepler 186-f is about 10% bigger than Earth and the f marker indicates that it’s the 5th planet in this system. It only receives about 30% of the sunlight that we get here on Earth and it’s likely a lot colder. But as Coughlin points out, we don’t know anything about its atmosphere, “if it has a thicker atmosphere than it could be plenty warm on the surface, and it would trap more heat and would be room temperature on parts of the planet but we don’t know for sure.”

Kepler 186-f orbits around a small, cool M-dwarf star. The surface mostly receives infrared light, so if there were life, it would have adapted to use that energy resulting in absorbing a different wavelength of light, which could change the common colors used by any plants or animals. One caveat with planets that orbit smaller stars like this is that they have to be closer to their host, and could experience flair events.

“When you get that close to a star you become tidally locked, the same way our Moon is tidally locked to us.” So Kepler 186-f would show one face to its star all the time, leaving one side of the planet scorching hot and the other in a deep freeze. However Coughlin points out that studies show that if it had an atmosphere at least as thick as Earth’s or thicker, high speed winds might carry the heat from one side to the cooler side making it an easier place for life to exist. “The wind would constantly be blowing, maybe around hundreds of miles per hour,” he says. That speed could carry warmer weather to the cold side, making it easier for life to exist.

In 2015, NASA announced the discovery of Kepler-452b, one of the most famous of the class of planets known as “super Earths.”

This planet made huge waves because it shares a lot in common with Earth. It orbits a G2 star like our own, and orbits its host star in 385 days. The planet is 50% bigger than Earth, and receives about 10% more energy from its star than we do.

“If you’re the size of the Earth you tend to be rocky, but as you get bigger — and you can get a bit bigger — but once you get past 50% bigger, the planets tend to be more like Saturn or Neptune,” Coughlin says. “With Kepler 452b the sun looks right, the amount of energy looks right, but the size is questionable.” It could be a very large Earth or it could also be a mini gas giant.

Since Kepler-452b’s host star is about a billion years older than our sun that means it’s also starting to evolve towards becoming a red giant. As a result there’s a chance that the planet could be too hot even now, and could have turned the planet into something similar to Venus.

“Proxima Centauri b It’s the closest exoplanet we’ll ever find to Earth, the distance is 4.2 light years away which is as close as we’ll ever get,” Coughlin says.

The star Proxima Centauri is also pretty small, at about 10% the size of our Sun. Proxima b gets about 70% of the energy that the Earth does, and it might be slightly larger than Earth. “We know it’s about 30% more massive than the Earth,” Coughlin says.

Proxima B also orbits an M-Dwarf star like Kepler-186f and these can be very active stars with regular and extreme stellar flares. The downside of orbiting stars that are so active like this is that they not only can irradiate any life, but can also sweep away any atmosphere.

Proxima B is also tidally locked like Kepler-186f creating yet another kind of extreme.“We’ve already found the closest one we’ll ever find and has the potential to learn a lot,” Coughlin says. “And with the upcoming launch of the James Webb Space telescope in 2018 we’re getting closer to the point where we can probe for atmospheres, especially when we find ones that are closer or around brighter stars.”

“One good thing [about M-Dwarfs] is that they live a long time,” says Coughlin. “Our sun is dying, but M-Dwarfs can live 100’s of billions of years which is plenty of time for life to evolve. You can have mass extinctions and then have time to rebuild.”

The super-Earth Kepler-62f was discovered in 2013. It’s host star is about three billion years older than our Sun and the planet takes 267 days to make one complete orbit.

“It’s another planet that’s 40% bigger than Earth, and likely rocky and it gets about 40% the amount of energy that we do,” Coughlin says.

Kepler- 62f orbits around a K-dwarf star, which on average are much more massive than M-dwarfs. It’s orbit is at a comparable distance from its star as Venus is to our Sun. Since the K-type star is cooler, the habitable zone is much closer. K-Dwarfs also have an extremely long lifespan, living somewhere around 30 billion years. Scientists think that -62f may be covered in water, but because it’s the farthest planet out in its system, it would require a pretty thick atmosphere to keep that water from freezing.

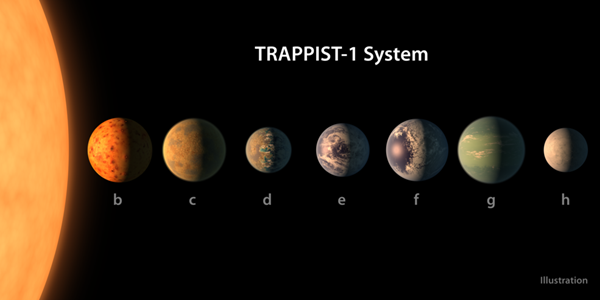

A family of three planets orbiting around TRAPPIST-1 were initially discovered in 2015. However upon studying the star more closely, they discovered that the star actually had seven different planets. The seven planets, TRAPPIST b, c, d, e, f, and g orbit around an ultra cool M-dwarf star and all fit within the orbit of Mercury and our sun. The TRAPPIST star is also only about the size of Jupiter, making it relatively small to host seven planets.

“The neat thing about this one is that there are three planets that are in the habitable zone, so if you had one planet that had a catastrophic event and another planet had something wrong the odds of finding at least one of those three to be more Earth like is pretty good,” says Coughlin.

One handy thing about having rocky planets close to one another like this is that if one is habitable then the accidental transport of life by comets or other impacts could pretty easily spread that life to the other bodies.

“I was excited when they found this system with seven planets, and three in the habitable zone. This discovery changed my view that M-dwarfs are good places to look for potentially habitable planets mostly because you don’t tend to have Jupiter-sized planets around M-dwarfs but you do tend to have rocky planets,” Coughlin says.

M-dwarfs like TRAPPIST-1, Kepler-186 and Kepler-62 are extremely common in the galaxy and because of their long lifespans it makes it a bit easier to find them.

What’s next for the exoplanets?

Planets like -452b and -62f are the closest analogs to Earth, orbiting more Sun-like stars at a distance we’re more familiar with. The hunt for more Earth-like planets is ongoing, but the super earth’s are actually pretty hard to find because they orbit their star at a similar length of time that we do. Waiting a few years to to see if there’s a dip in the light in front of the star is pretty challenging.

“The Kepler mission had to stare at the same patch of sky for over four years to find planets like Earth,” Coughlin says. “The big planets close to their star around small stars are the easiest to find.”

Luckily, new exoplanet announcements have become the regular for astronomers. And there are upcoming missions focused solely on searching for more exoplanets. TESS is the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite planned to launch in 2018 and CHaracterising ExOPlanets Satellite (CHEOPS) also launching in 2018. Jeff Coughlin thinks we’ll know sometime in the next twenty to thirty years about the atmospheric conditions around some of these planets because after a few more generations of advanced telescopes the technology will be there to detect water vapor and other chemical signatures. The most important thing they’ll be looking for is what keeps us alive. “If we find oxygen around another planet it will be really exciting because the only thing on Earth that produces oxygen is life.”