NASA’s Cassini spacecraft launched on October 15, 1997, from Cape Canaveral, Florida. It slung around Venus, Earth, and Jupiter, using the gravitational potential of each planet to redirect its path during its seven-year journey to Saturn.

Soon after arriving at the gas giant in 2004, Cassini released its passenger, the Huygens probe. This ESA-built probe delved into the rich atmosphere of Saturn’s largest moon Titan, providing the first close look at the complex world.

During Cassini’s thirteen years in orbit around Saturn, it danced among the moons and rings to study the world in unprecedented detail. Mission scientists learned to use Titan as a dance partner for the spacecraft, dipping into the moon’s gravitational potential to fling Cassini onto new trajectories while conserving precious fuel. But even efficient spacecraft driving burns some fuel — with 6,504 pounds (2,950 kilograms) of propellent burned and just 1 pound (0.5kg) left in Cassini’s tank, it’s time to end the mission and crash the spacecraft into Saturn while NASA’s team still has control.

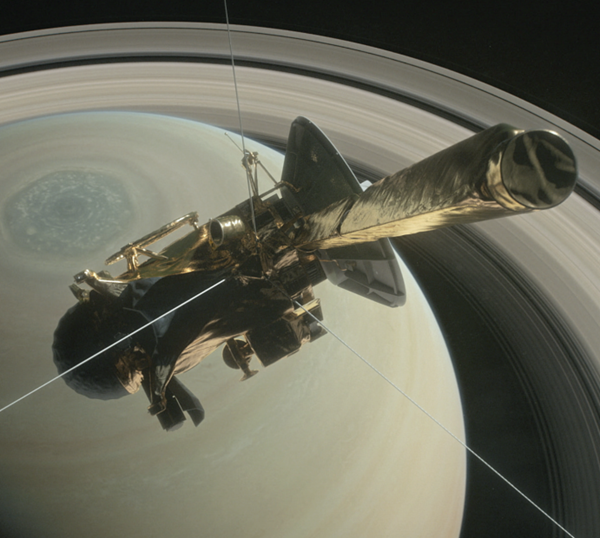

Faced with dwindling propellent supplies, Cassini’s engineering team dreamt up an audacious plan to get the most interesting science results possible before safely disposing of the spacecraft. This plan was the Grand Finale, 22 ever-more-daring orbits skimming Saturn’s atmosphere and darting between the rings until finally, inevitably, steepening Cassini’s near-misses into a final plunge directly into Saturn.

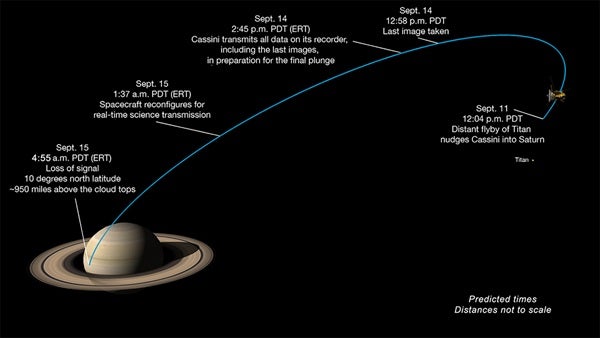

On September 9, 2017, Cassini began its final orbit around Saturn as its mission team started to gather in Pasadena, California, for a final science meeting. On September 11, 2017, the spacecraft swung past Titan for a gravitational nudge as it had so many orbits before, but this time in a “goodbye kiss” nudging Cassini so that after it reached apoapse September 12, it would start the long fall directly into Saturn’s gravitational well

At 12:58 p.m. Pacific time on September 14, 2017, the Cassini spacecraft will look around Saturn’s system for the final time. Its cameras will capture a wide view of the planet and its rings, watch Enceladus set behind Saturn, glance at a half-phase hazy Titan, check one last time if the “Peggy” disturbance in the outer rings has broken free as a new moon, and observe the strange shape of propellers in the rings. Finally, Cassini will look ahead into the darkness on the night side of Saturn, taking its final photograph straight ahead at the patch of the gas giant that will soon destroy it.

By 1:22 p.m., Cassini’s camera will shut down for the final time. The spacecraft will align its antenna with Earth and downlink the photographs via the Deep Space Network. The transmission will start in Goldstone, California, then get handed off to Canberra, Australia, as Earth turns below the steady stream of data.

For 13 years, Cassini has explored, gathered data, and sent it back to Earth in discrete packages later. That changes just after midnight on September 15th, when the spacecraft transitions to real-time transmission of streaming data from its few instruments still switched on.

In the wee hours of the morning, the people who have dedicated their careers to Cassini will gather to stand vigil, the core operations staff at Mission Control in the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the remaining scientists and engineers across town at the California Institute of Technology. At 4:00 a.m. Pacific time, NASA TV will stream a live broadcast so others around the world can follow along.

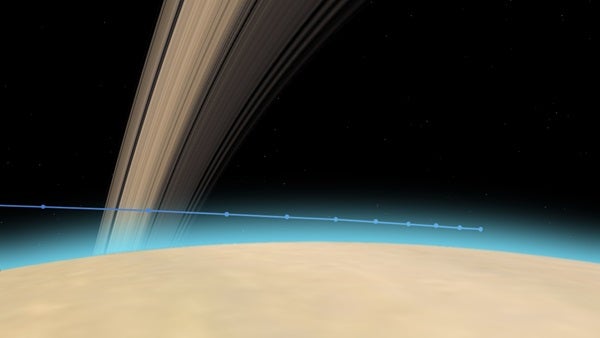

The spacecraft is expected to start feeling the effects of Saturn’s atmosphere at 1,193 miles (1,920km) above the cloud tops at 4:43 a.m. Pacific time. It will use its thrusters to try to maintain an orientation pointed at Earth and relaying data for as long as possible, but the spacecraft designed to operate in deep vacuum will rapidly be overcome by Saturn’s relentless storms. Wrenched out of position, Cassini’s signal will be lost with no chance of recapture.

By dawn, the mission will be over.

And yet, the data will live on. After rounds of congratulations on a mission well done and condolences on a mission ended, the scientists will get back to work. For some, it will be paperwork. For others, interpreting the final data streamed on Cassini’s descent. For many extending beyond the mission team, it will be analyzing the 635 GB of scientific data collected and adding to the 3,948 papers already published. For more than a few, it will be taking the lessons learned during Cassini and applying them to other missions, including NASA’s plans for a Europa Clipper exploring the ocean world circling Jupiter. And for all, it will be a time of reflection.

Goodbye, Cassini. Thank you, and good luck.