Key Takeaways:

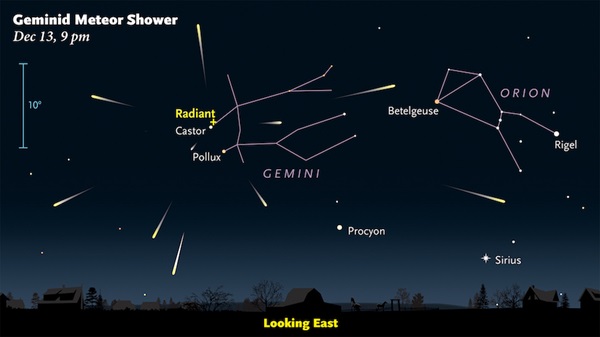

Step outside after dark this week and you can watch chunks of an asteroid burn up in Earth’s atmosphere. Behold, the Geminid meteor shower, which is renowned as the year’s best.

At peak Geminids, you could catch a shooting star every minute, and this year the moon won’t be bright enough to foul the show. That main action arrives just past 9 p.m. local time Wednesday and lasts until dawn. “The Geminids are rich in fireballs and bright meteors so that makes them very good to observe,” says Bill Cooke, who runs NASA’s Meteoroid Environment Office.

And it’s not only amateurs excited about this year’s show. Just a day after the Geminids peak, the asteroid behind the meteor shower, 3200 Phaethon, will pass closer to the planet than it has since 1974 — before it was discovered. Astronomers are ready; they’re hoping to get the best images ever of its surface and finally settle an old debate: How did an asteroid — instead of a comet — cause a meteor shower.

To sweeten the plot, the best images are likely to come from Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. And on Tuesday, astronomers got the instrument’s planetary radar system back online for the first time since Hurricane Maria.

“It appears everything is on track, and they should have spectacular images,” says Paul Chodas, who manages NASA’s Near-Earth Object Program at JPL. “We don’t see many large ones like this getting close to the Earth’s orbit. It’s a fabulous opportunity.”

A Special Shower

All meteor showers are made of small, icy particles ripped from much larger objects — usually comets — that cross Earth’s path. As our planet passes through this debris, the particles burn up in the atmosphere, creating meteors. For example, ice chunks from Halley’s Comet create the annual Orionid meteor shower.

But the Geminids, well, the Geminids are special.

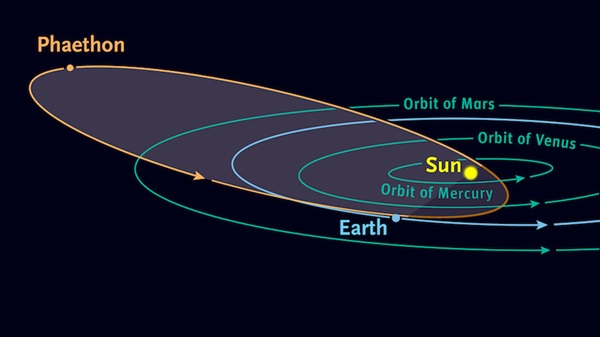

Until 1983, astronomers didn’t know where they were coming from. That year, NASA’s Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAF) discovered 3200 Phaethon. Its highly elliptical path crosses Earth’s orbit, and astronomers soon realized the timing lined up well with the Geminids—that’s odd.

Asteroids don’t usually cause meteor showers. So, astronomers aren’t sure what to think of Phaethon. Its composition is closer to an asteroid, but the space rock also has an orbit more like a comet. It’s possible that Phaethon formed when a larger asteroid split into pieces sometime in the last 800 years. The meteors would have formed during the break up, meaning each shooting star you see this week was actually born centuries ago. There is another possibility, too. Many astronomers think Phaethon is a sun-baked comet that lost all its volatiles — the stuff that burns off easily, like water.

“The idea is that either Phaethon is an extinct comet, or it’s a piece of an asteroid that broke apart,” Cooke says. “We’ve been trying to find out for decades and haven’t had much luck,” he adds.

A Somewhat Close Encounter

Scientists hope to gather more clues this week when Phaethon passes some 6 million miles from Earth. That’s relatively close for a 3-mile-wide asteroid, and closer than any other named asteroid. However, there’s no need to worry as it’s still some 25 times farther away than the moon.

Phaethon won’t pass this close again for another 76 years. So astronomers are jumping at the opportunity. Down at Arecibo in Puerto Rico, scientists and engineers just managed to get their instrument back online, making radar observations this week after it was damaged during Hurricane Maria.

The massive dish survived the storm intact, but smaller instruments were destroyed. Officials told the Washington Post that the instrument needed some $4 to $8 million worth of repairs. Arecibo, which has been running on generator power since October, has just been reconnected to the grid. In their return to operations on Tuesday, a team of astronomers successfully detected a known near-Earth asteroid. That has them primed for Phaethon later this week.

“Many asteroid scientists will be taking advantage of the close pass to take observations, including radar imaging,” says NASA’s planetary defense officer Lindley Johnson. “Arecibo has been doing a real pushup this last week to get back online prior to this opportunity.”

Arecibo planetary scientist Edgard Rivera-Valentín says they’ll observe Phaethon from Dec. 15 through Dec. 19. And depending on the resolution, they might capture fine details like craters, ridges and even boulders.

“We will know much more once we get the first images of Phaethon on Friday,” he says.

But even a gorgeous picture of the space rock might not be enough to give a full answer.

“Settling the asteroid/comet debate will be difficult and I don’t know that images alone would make the answer perfectly clear,” adds fellow Arecibo astronomer and self-titled “planet defender,” Patrick Taylor.

Still, astronomers say getting a glimpse at Phaethon’s surface should at least provide new clues and help astronomers better model its origins.

Catch a Shooting Star

And they’re not the only ones looking up this week. Cooke’s team is also watching the skies.

Last year they saw 20 meteorites impact our satellite’s surface during the Geminids’ peak.

Cooke works in NASA’s Meteoroid Environment Office, and he says studying those impacts has some practical importance, too. A pingpong ball-sized Geminid traveling at tens of thousands of miles per hour could really mess up a future lunar base. And not all meteorites are that small. Cooke’s team saw a space rock the size of a bowling ball hit a few years ago during another meteor shower. When NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter passed over the impact site, there was a fresh crater some 60 feet wide.

“If you were an astronaut several miles away you would have to worry about falling debris,” Cooke says.

The Geminids don’t just fall to the lunar surface, either. Unlike the moon, Earth has a thick atmosphere that typically stops shooting stars from reaching the ground during meteor showers. But, once again, the Geminids are an exception — they’re known to reach Earth’s surface.

Cooke is part of network that tracks the heavens for bright meteorites all year using small, wide-angle imagers called All-Sky Cameras. He estimates there are roughly 100 of these cameras in North America, and even more worldwide.

His hope is that the cameras will catch a bright Geminid as it enters Earth’s atmosphere and triangulate where the meteorite fell. “One of the dreams is to pick up a Geminid and track it all the way to the ground,” Cooke says, admitting the odds are long. “Every year I hope to see in my cameras.”