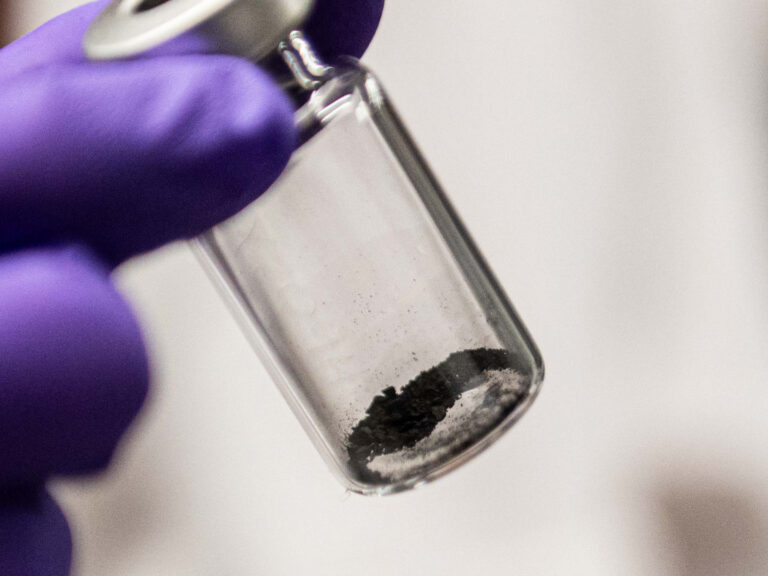

Though the progenitor of the explosion had an initial mass of over 10,000 metric tons, only about 0.1 percent of that mass is believed to have reached the ground, indicating that something in the upper atmosphere not only caused the rock to explode, but also caused it to disintegrate much more than expected.

A relatively small meteor streaked through the sky and eventually exploded over the Chelyabinsk region of Russia on February 15, 2013. With a blast energy equivalent to roughly 500,000 tons of TNT, the explosion created shock waves that caused damage to thousands of buildings and injured nearly 1,500 people.

Today, a team of researchers published a study in Meteoritics & Planetary Science that proposes a new and previously overlooked mechanism for air penetration in meteoroids, which could help explain the powerful breakup of the Chelyabinsk meteoroid.

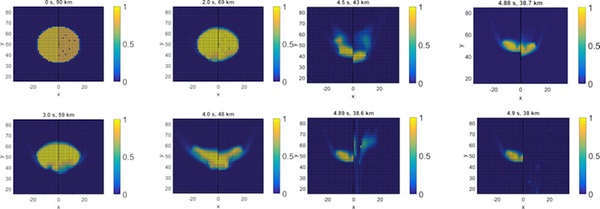

According to the paper, as a meteoroid hurtles through Earth’s atmosphere, high-pressure air in the front of the object infiltrates cracks and pores in the rock, which generates a great deal of internal pressure. This pressure is so great that it causes the object to effectively blow up from the inside out, even if the material in the meteoroid is strong enough to resist the intense external atmospheric pressures.

“There’s a big gradient between high-pressure air in front of the meteor and the vacuum of air behind it,” said the study’s co-author Jay Melosh, a professor of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences at Purdue University, in a press release. “If the air can move through the passages in the meteorite, it can easily get inside and blow off pieces.

“I’ve been looking for something like this for a while,” Melosh said. “Most of the computer codes we use for simulating impacts can tolerate multiple materials in a cell, but they average everything together. Different materials in the cell use their individual identity, which is not appropriate for this kind of calculation.”

Though this process of air penetration is a very effective way for our atmosphere to shield us from smaller meteoroids, larger and denser ones will likely not be as affected by it. However, the more we can learn about how different meteoritic materials explode, the more prepared we can be for the next Chelyabinsk.