Key Takeaways:

- A piece of foam striking the Columbia shuttle caused significant damage.

- This damage led to the shuttle's disintegration upon re-entry.

- The accident resulted in the deaths of all seven crew members.

- The tragedy prompted major safety improvements in NASA's space program.

[Editor’s note: This article was updated Jan. 26, 2023.]

NASA is holding its annual Day of Remembrance today, Thursday, Jan. 26, to honor the crew members who lost their lives during the Apollo 1 fire and the Challenger and Columbia space shuttle disasters, as well as other NASA employees who have perished while advancing space exploration.

This year, 2023, marks the 20th anniversary of Columbia’s last space shuttle mission, which suffered a catastrophic and fatal end on Feb. 1, 2003. The unfortunate event shook the science community and the public, but the lessons taken away from the incident overhauled NASA’s approach to safety concerns and future space travel.

Columbia’s last mission

On January 16, 2003, Columbia embarked on its 28th space shuttle mission, designated STS-107, to carry out a series of microgravity science experiments. However, about 80 seconds into the shuttle’s launch from the Kennedy Space Center, a large piece of foam insulation split off from the “bipod ramp” — a piece used to attach the external tank to the shuttle.

Engineers used camera footage to review the incident, and found that the suitcase-sized piece of foam struck the shuttle’s left wing as it fell. However, ground workers weren’t able to determine exactly where the damage occurred or how severe it was. Furthermore, NASA engineers believed that if extensive damage did occur, the crew members wouldn’t be able to remedy the situation while the shuttle was in orbit.

This was the fifth time that foam had been observed breaking off of a bipod ramp, and the problem had become so common that it even had a name: foam shedding. Since the four previous cases of foam shedding occurred without incident, NASA became accustom to the phenomena and didn’t take many preventative measures to stop it from happening in future launches.

On the morning of Feb. 1, 2003, as the Columbia mission was beginning its descent back to Earth, Mission Control starting receiving unusual readings from the tire pressure and temperature sensors on the shuttle’s left wing. They were briefly able to contact the crew, but lost communication before they were able to address the concerns.

Shortly after the shuttle crossed the coast of California, while it was at an altitude of over 230,000 feet (70,100 meters), civilians started seeing debris fall from the sky. Several unsuccessful attempts at communication were made over the next few minutes as Columbia traveled over California to Texas.

Around the time that Columbia should have been landing at the Kennedy Space Center, eyewitnesses near Dallas began reporting that the shuttle had disintegrated overhead. At 9:12 a.m., Entry Flight Director LeRoy Cain instigated NASA’s contingency plan and alerted search and rescue teams in Texas and Louisiana.

Search and rescue

Search and rescue teams, along with thousands of volunteers, spent several weeks combing through parts of Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas trying to recover as much of Columbia as possible. NASA was eventually able to recover 84,000 pieces of debris, which added up to about 40 percent of the space shuttle.

Within the thousands of pieces of debris, NASA was able to locate the remains of each of the crew members, verified through DNA. An investigation into the incident later determined that the foam shed during Columbia’s launch created a hole in the left wing, which caused extensive damage to the shuttle’s sensors and allowed atmospheric gas to leak into the cabin during de-orbit. The resulting damage caused the craft to lose control and disintegrate as it re-entered Earth’s atmosphere, killing everyone onboard.

The search team also recovered aspects of science experiments conducted onboard, including groups of small worms, known as Caenorhabditis elegans. The study involved feeding the worms a synthetic nutrient to see if they would grow in space, but due to the amount of time that it took to recover the worms, the data was lost. However, the fact that many of the worms, which are only about 1 millimeter long, survived the crash with minimal heat damage was a scientific discovery in itself.

The aftermath

After the incident, the Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CIAB) was formed to thoroughly investigate the shuttle’s destruction. Through the investigation, they determined that NASA had a tendency to overlook potential problems, like foam shedding, if they hadn’t caused major incidences in the past. They also concluded that a space-based rescue attempt could have been made by moving up the launch of the planned Atlantis shuttle to Feb. 10 (Columbia could have orbited until Feb. 15).

The CAIB also issued recommendations to NASA to overhaul their approach to safety by actively seeking out any potential problems and mitigating them before they occur. NASA took the boards advice by suspending missions for over two years while they redesigned their external tank and initiated additional safety precautions.

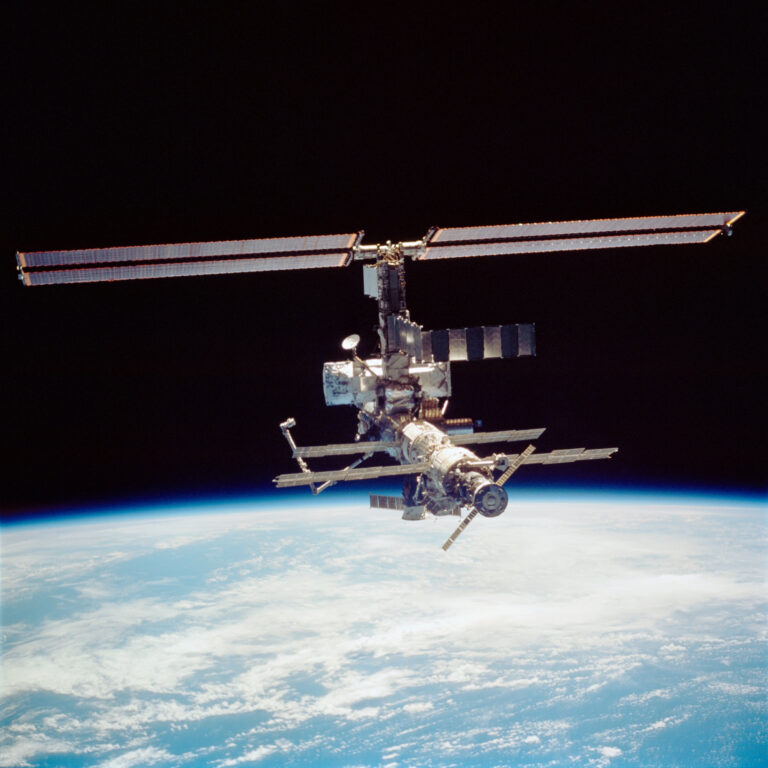

In July 2005, they tested new safety measures — such as additional cameras to monitor foam shedding — on the Discovery space shuttle mission STS-114, but they found that more foam had broken off of the shuttle than expected. This forced them to again delay any further missions until July 2006, from which the missions continued until the International Space Station was complete. The station’s 2011 completion marked the end of the Space Shuttle Program.

Public reaction

As the nation and the science community grieved the loss of Columbia’s crew members, officials reiterated to the public that, although the tragic incident occurred, the quest for space exploration was far from over.

“We are now determined to move forward with a careful, milestone-driven return to spaceflight activities, and to do so with the utmost concern for safety, incorporating all the lessons learned from the tragic events of February 1st. That’s exactly what we will do,” said Sean O’Keefe, NASA’s administrator from 2001-2005, in a statement.

“We are about to begin a new chapter in NASA history, one that will be marked by a renewed commitment to excellence in all aspects of our work, a strengthening of a safety ethos throughout our organization, and an enhancement of our technical capabilities,” added O’Keefe.

Then-president George W. Bush released a statement on the day of the Columbia disaster, commemorating the astronauts who gave their lives, and also reiterating the importance of space exploration.

“In an age when space flight has come to seem almost routine, it is easy to overlook the dangers of travel by rocket, and the difficulties of navigating the fierce outer atmosphere of the Earth. These astronauts knew the dangers, and they faced them willingly, knowing they had a high and noble purpose in life,” said Bush in a presidential address. “The cause [for] which they died will continue. Mankind is led into the darkness beyond our world by the inspiration of discovery and the longing to understand. Our journey into space will go on.”

Although there is only one day each year formally dedicated to remembering those who lost their lives in the pursuit of space exploration, the crew members’ legacies continue to live on each day. Observances for NASA’s annual Day of Remembrance today will be held at Virginia’s Arlington National Cemetery, Florida’s Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex, and multiple other NASA centers.