Brian Keating is a professor of physics and astronomy at the University of California San Diego, and the author of Losing the Nobel Prize: A Story of Cosmology, Ambition, and the Perils of Science’s Highest Honor (http://amzn.to/2sa5UpA). His book, which will be released April 24, 2018, is a deeply personal journey that illuminates both the ultimate questions that cosmologists seek to answer, and the problems that we, as human beings, generate in the pursuit of those answers.

Our universe started with the Big Bang and, many cosmologists believe, underwent an extremely rapid and brief period of inflation when it was just a trillionth of a trillionth of a trillionth of a second old. Inflation solves many of the “problems” left unaddressed by the current Big Bang theory, and explains many of the characteristics of the universe we observe today. But inflation remains unproven. Seeing the signs of inflation, then, will surely result in that highest honor, a Nobel Prize in Physics, for significantly advancing humanity’s understanding of the birth of our universe.

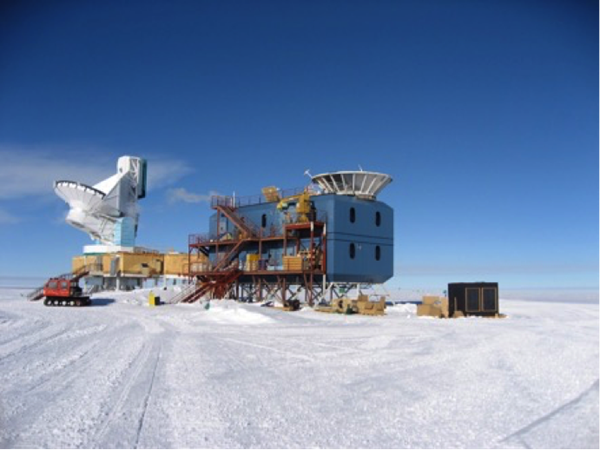

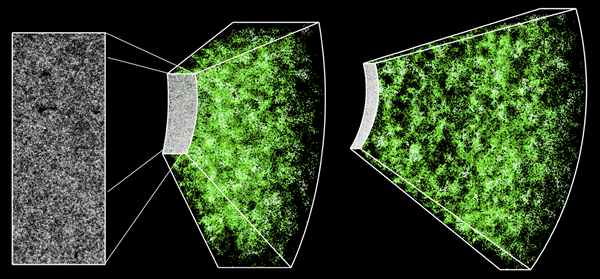

Cosmologists study relics such as the cosmic microwave background (CMB), which represents the universe when it was about 380,000 years old, for clues about those earliest moments. The BICEP2 project was designed to search for signals within the CMB — specifically, a characteristic called its B-mode polarization — that could prove this inflationary period had occurred. In March 2014, the BICEP2 team announced they’d found what they were looking for: direct evidence of cosmic inflation. This was surely Nobel Prize-winning stuff.

But soon after, controversy followed. The story of BICEP2 ultimately ended with the confirmation that the signal researchers had found was not due to inflation, but instead, resulted from dust inside our own galaxy. The Nobel Prize had been lost — how had it all gone wrong?

Keating created BICEP (Background Imaging of Cosmic Extragalactic Polarization), the project upon which BICEP2 was built. In Losing the Nobel Prize, he offers a firsthand account of the BICEP2 results and controversy, including a behind-the-scenes look at the project’s progression, and the decisions and driving factors that led to the March 2014 announcement. He also covers the history of the Big Bang and inflation theories, explaining and illustrating what we currently believe about our universe’s earliest epochs in a clear, engaging, and easy-to-understand manner. Whether you’re familiar with these ideas behind the evolution of our universe or have never heard the word “inflation” before, Keating’s narrative ensures you’ll have the background you need to understand why this result was so sought-after — and the difficulties researchers faced in trying to make such a measurement.

But this is only part of the story. Losing the Nobel Prize also takes a deeper look at the state of the Nobel Prize today, and how it has shaped — and hindered — the way science is done. For a shot at the Nobel, scientists are focused on getting results out as quickly as possible, keeping those results to themselves until they are made public, and cutting both supporting and competing groups out of their research network (only three people can win the Nobel in a single category each year, but much of today’s science is achieved by large collaborations). But, Keating argues, these are exactly the problems that scientists should seek to solve — better science comes from inclusivity, collaboration, and innovation.

The book opens with a history of the Nobel Prize, telling the tale of Alfred Nobel’s early life and later establishment of the prize, including the intent behind it. It closes with a message that science should be pursued humbly and genuinely, rather than for the sake of success. Sprinkled throughout the narrative are three “broken lens” chapters that highlight Keating’s concerns with regard to the Prize’s detrimental effects on science today. These chapters each focus on a specific problem: the Prize’s effect on the way cash, credit, and collaboration are pursued and perceived.

Ultimately, Keating argues, the problem is not the Nobel itself. Getting rid of the prize isn’t the solution. But the Nobel needs to change, and with it, the way science is accomplished, shared, and celebrated.

Losing the Nobel Prize: A Story of Cosmology, Ambition, and the Perils of Science’s Highest Honor is now available for pre-order on Amazon; it has also been selected as one of Amazon’s Ten Best Nonfiction Books this month.

AM: Cosmology in particular is a field that fascinates the public, but also isn’t a subject that most people encounter other than in sensationalized headlines. Do you think that the BICEP2 results and the window they opened onto the current scientific process have changed the public’s opinion on cosmology, or affected their confidence in the field?

BK: Cosmology has several things that both fascinate and irritate. Both revolve around the essential controversial nature of cosmology. First of all, we only have one cosmos (unless we live in a multiverse, then all bets are off!). So we cannot actually do experiments or study statistical samples. We can only rely on the data that comes to our telescopes after traversing the entire universe. On the way, things can get pretty messy. Secondly, cosmology of all the sciences, is closest in themes to religion, a subject which obviously arouses great passions in both scientists and laypeople alike. (Some of those themes are explored here: https://youtu.be/9Z5u0jDj7dg)

Regarding the irritating nature of cosmology: after our results were disconfirmed, Dartmouth astronomer Marcelo Gleiser said the BICEP2 experience “harms science because it’s an attack on its integrity . . . It gives ammunition for people to say, hey look those scientists don’t know what they’re talking about in cosmology and they don’t know what they’re talking about in general.” But I disagree because, in the end, the public did get a science lesson. Science is messy because nature is messy. Scientists are not infallible robots; we are human. We didn’t blunder: we didn’t leave the lens cap on or use dirty test tubes. Unlike cold fusion or faster-than-light neutrinos, BICEP2’s results were reproducible. In fact, we have more confidence than ever in BICEP2’s actual B-mode detection significance— which is an amazing accomplishment when you consider these signals are billions of times colder than even the frigid polar landscape where BICEP2 lived for three years.

BICEP2 showed the public how science works: you put out a result, and other scientists work to test the result. You put all your cards on the table, and leave it all out there for your critics. If and when they attack, you defend until you can defend no longer and the attacks subside. Only then, when both critic and supporter collapse, exhausted, can science be said to be settled.

So I’m not worried. Cosmology will survive BICEP2, and the many more messy episodes to come!

AM: Can you give a brief explanation of the type of cosmic dust responsible for the signal that BICEP2 picked up, and how it managed to masquerade as the signal you wanted?

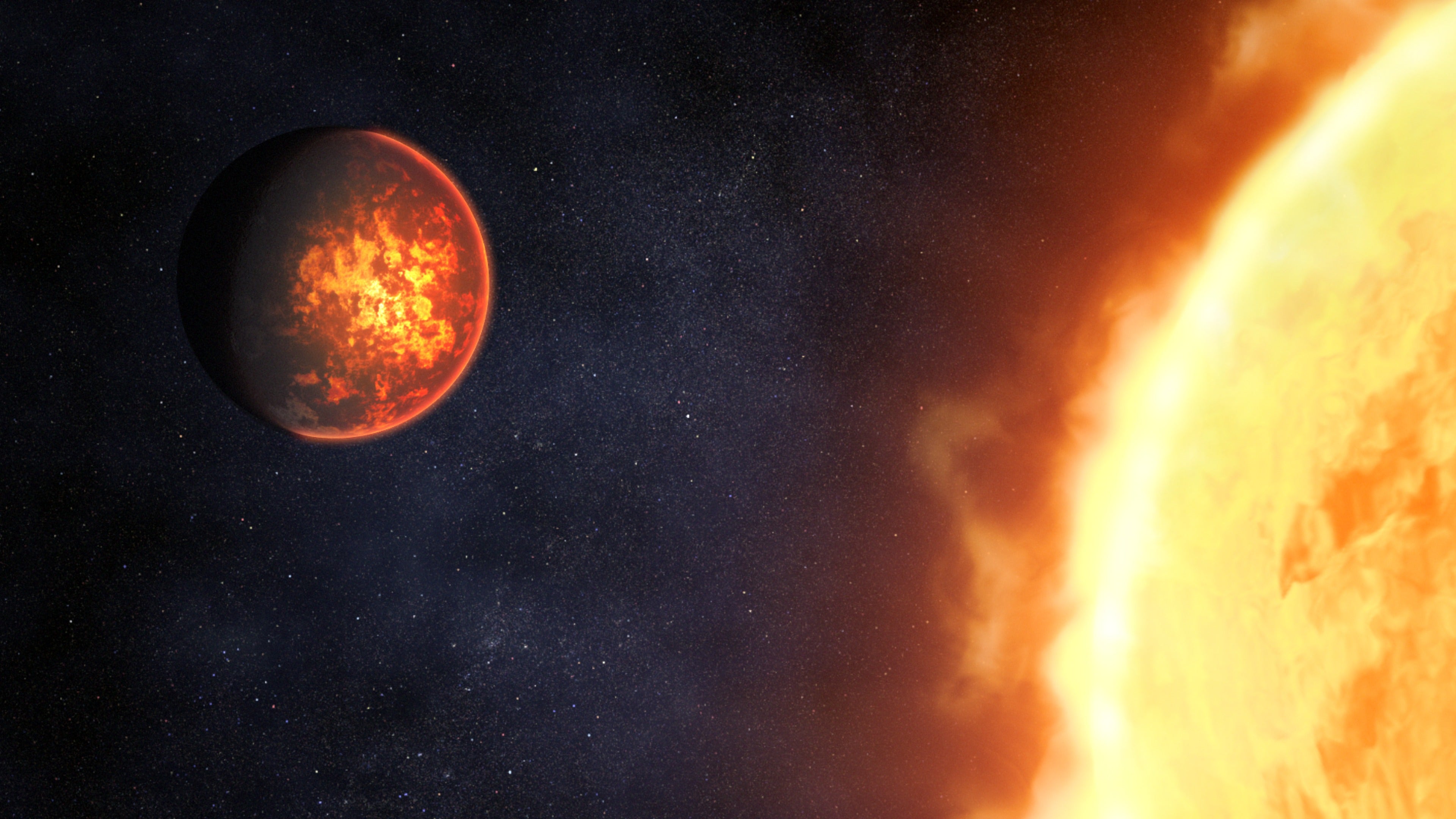

BK: The signal that we saw seemed to be the imprimatur of inflation. But, eventually it was understood to be dust in our galaxy, which scatters and and polarizes the CMB light that we really want to see. It’s sort of like a car’s dirty windscreen: not only does it diminish the light of the road ahead, it distorts it as well. In our case, it can mimic the very B-mode signals we’re looking for. I didn’t realize at the time, but dust has always been a cosmic companion leading astronomers astray since the very first telescope ever used to look up the cosmos by Galileo.

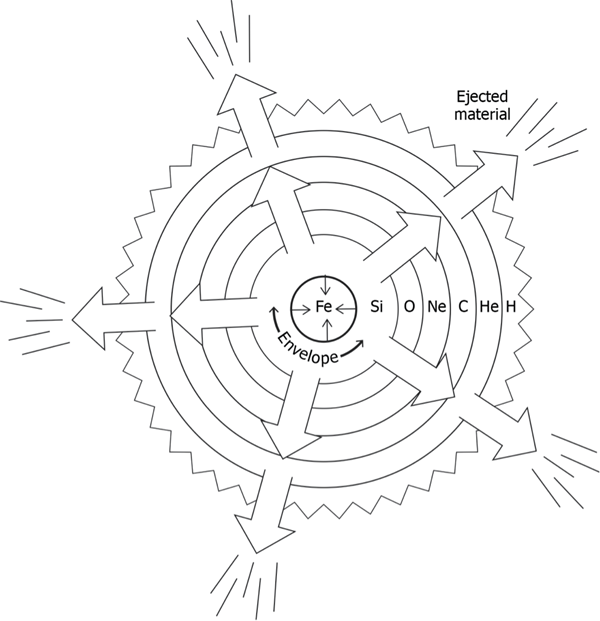

The interstellar medium — the stuff between the stars in our galaxy—is a cold and vacuous place. Eventually, the molten blasted away in the supernova condenses into solid particles of iron. We have copious evidence for the end product of this process right here on Earth. Every day, our planet plows into tons of micrometeorites, many of which, upon magnification, turn out to be tiny iron whiskers, which scientists believe originated inside supernova explosions. Iron dust particles are magnetic, and the magnetic fields in the Milky Way align them, just like tiny compass needles. These needles can then emit their own thermal heat in the form of microwaves, which owing to the efficient alignment by galactic magnetic fields, is highly polarized.

BK: Awards are important because they allow for leverage of a scientist’s impact, just as an Oscar winner can choose her projects however she wishes. The Nobel Prize is the highest leverage of all, not only science’s highest accolade, but arguably humanity’s as well. It gets you tenure, funding, and fame. And I think the Nobel Prize has a resiliency, and there is a desire to keep it as it is. But I think what we’re seeing in society now a de-constructivism, that people are not happy with large sclerotic institutions from Hollywood to Washington, to sports; fields that were not inclusive and forward thinking, and now have to be reformed. And it’s for their own good. Change is difficult and I think my book is written in such a way to give concrete ideas for people to transform this accolade so that it remains worthy of aspiration. In doing so, it will reflect how science is done today, not in 1895 when Alfred Nobel wrote down his will. Science a vibrant, ever-changing, dynamic entity and I think to treat Nobel’s will as a living document would be to transform it so it reflects and benefits the broad spectrum of what science is today.

To do so, some colleagues and I have set up a community (losingthenobelprize.org) where people can advocate for change and suggest winners, suggest changes to the structure of the Nobel Prize as well. I don’t feel obligated to complete the task, but I can’t desist from it either.