The search for this mysterious breed of black hole isn’t a new one, but identifying them requires two tricky aspects — timing and location. One of the few ways to identify this type of black hole is to observe a star being torn apart by its strong tidal forces. This occurrence, known as tidal disruption event, creates a massive and bright radiation flare. If researchers happen to witness such an event, they can study the radiation flare and begin to determine the black hole’s properties.

“We feel very lucky to have spotted this object with a significant amount of high quality data, which helps pinpoint the mass of the black hole and understand the nature of this spectacular event,” said lead author of the study, Dacheng Lin of the University of New Hampshire’s Space Science Center, in a press release. “Earlier research, including our own work, saw similar events, but they were either caught too late or were too far away.”

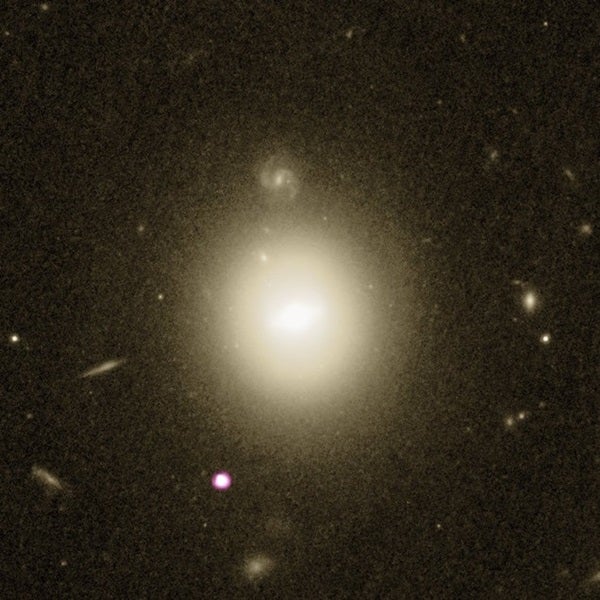

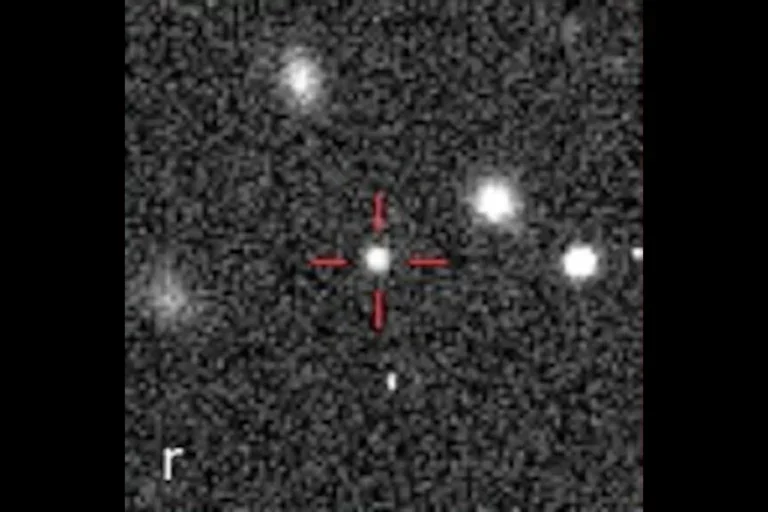

Their new research used NASA’s Swift Satellite and Chandra X-ray Observatory, along with ESA’s XMM-Newton X-ray Observatory, to observe a massive radiation flare in 6dFGS gJ215022.2-055059, a galaxy about 740 million light-years from Earth. The flare was created during a tidal disruption event in which a star got too close to its galaxy’s center and was torn apart by the strong gravitational forces of its central black hole.

During the disruption, part of the star’s material was ejected out into the galaxy, while the remainder was consumed by the black hole. As it was absorbed, the matter rose to millions of degrees and created a distinct X-ray radiation flare. The flare’s immense heat caused it to reach maximum luminosity and become visible, allowing researchers to study it in detail. From their observations, they were able to determine that the disruption was caused by a black hole fifty thousand times as massive as the Sun — directly identifying an IMBH for the first time.

Despite having a tough time making the long-awaited discovery, the researchers believe that IMBHs are prevalent throughout the universe.

“From the theory of galaxy formation, we expect a lot of wandering intermediate-mass black holes in star clusters,” said Lin. “But there are very, very few that we know of, because they are normally unbelievably quiet and very hard to detect and energy bursts from encountering stars being shredded happen so rarely.”

With tidal disruption events being such uncommon occurrences, researchers need to be observing the right place at the right time. Since Lin and his team happened to come across one by chance, they believe that most IMBHs are simply lying dormant, waiting to devour a star and make their presence known. Continuing to hunt for their existence will not only expand our knowledge of black holes, but also the evolution of galaxies and the configuration of our universe.