Fifty years ago today, on September 18, 1968, the Soviet Union’s Zond 5 spacecraft circled the Moon, ferrying the first living creatures known to have orbited another world. On board were two Russian steppe tortoises along with some worms, flies and seeds.

“It really was one of those last hurrahs for the Soviet spaceflight program because it was one of the last times they were able to preempt the Americans in any real way,” says Cathy Lewis, the international space program curator for the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

Beating the Russians

But understanding why the Russians sent tortoises instead of cosmonauts requires a quick dive back in time to 1968. More than a decade had passed since Sputnik terrified the West with Soviet spaceflight superiority. And thanks to infighting and funding shortfalls, Russia had fallen far behind in the Moon race.

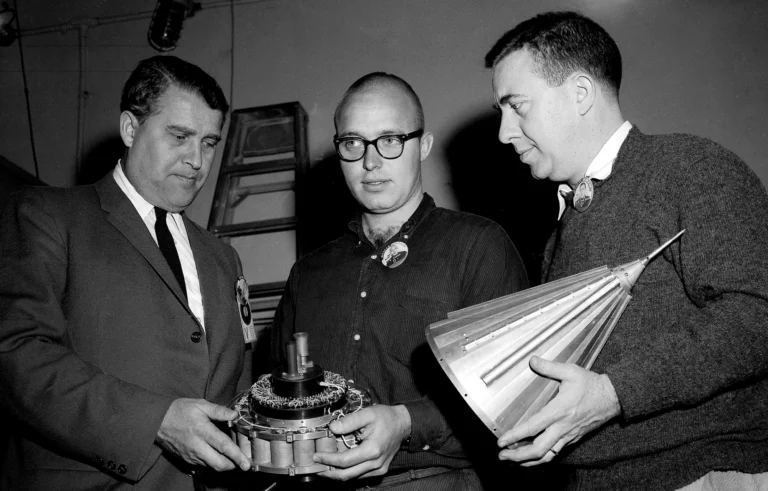

NASA now had the Saturn V rocket. And the Apollo program was just weeks away from its first crewed test flight. Meanwhile, the Soviets still didn’t have a launch vehicle that could carry a spacecraft around the Moon with the heavy cargo — oxygen, food, water — needed to support human life. The Soyuz also had a terrible track record.

The prior year, cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov died a horrific death when he was incinerated in his spacecraft as it fell back to Earth. Many, including Komarov, had even expected he’d die in the shoddy Soyuz.

“The program development was sped up to an unreasonable rate,” Lewis says.

America Unimpressed

Lewis says that — contrary to popular narrative — by 1968, few experts thought Russia could beat the United States to the Moon. Zond 5 was simply a last ditch effort at snatching a national victory. If they couldn’t send Yuri Gagarin, they could at least send a Russian tortoise.

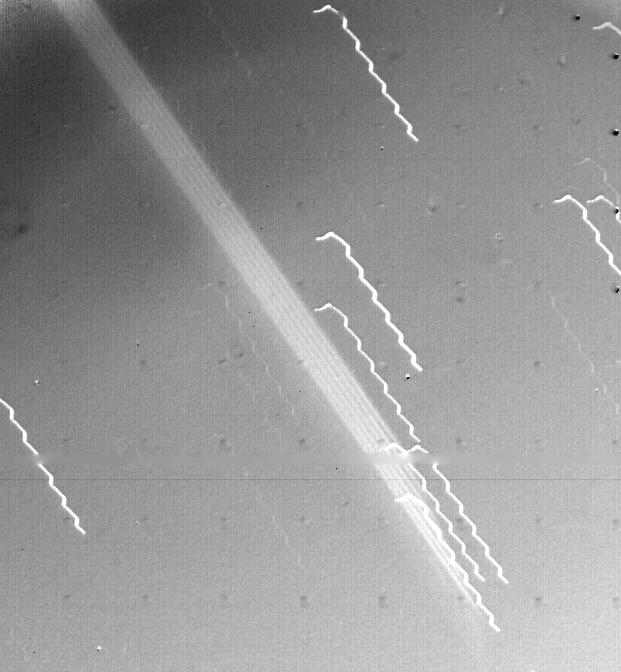

The mission worked — mostly. On September 21, Zond 5 had a rough re-entry paired with guidance program problems, and it splashed back down in the Indian Ocean instead of Kazakhstan. An American vessel saw it fall back to Earth. The crew was able to snatch photos before the Soviets could recover the spacecraft, Lewis says. And that told American intelligence even more about how far behind the Soviets were.

The tortoises were little worse off for the trip. Reports say they’d shed some body weight but were otherwise unharmed.

Global headlines heralded the feat. But not everyone was impressed — especially the engineers at NASA. “Some people recognized it for the Hail Mary pass that it was,” Lewis says. “They came to the conclusion that this was no threat.”

Past reports suggested the Apollo 8 mission was bumped up after Zond 5 showed the Soviets could send life to the Moon. But Lewis says it was obvious the spacecraft couldn’t support human life, so there was no need to speed up American missions to the Moon because of it.

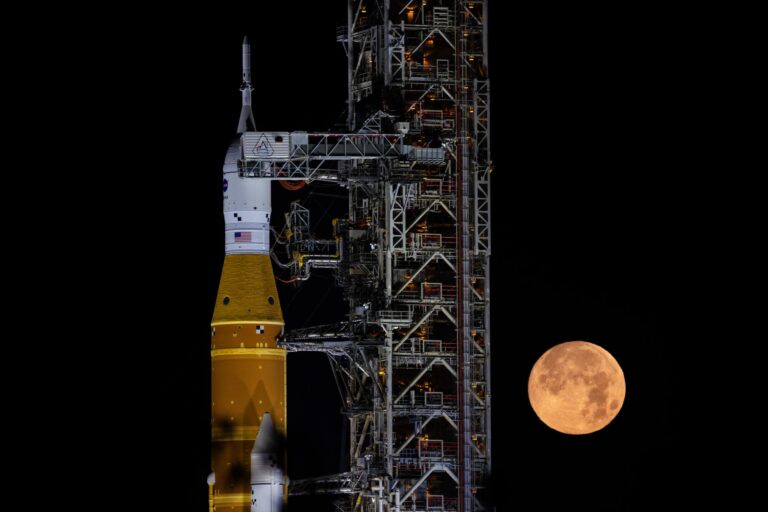

And while that first Soyuz capsule couldn’t have safely carried humans to our satellite, 50 years later it’s now the only spacecraft that can carry humans into space at all. The U.S. is still paying Russia for rides to the International Space Station on board Soyuz capsules.

But Lewis cautions against taking the narrative too far. She compares it to cars now and cars 50 years ago. “It’s not your 1968 Mustang; it’s a 2018 Mustang,” she says.