Voyager’s long haul

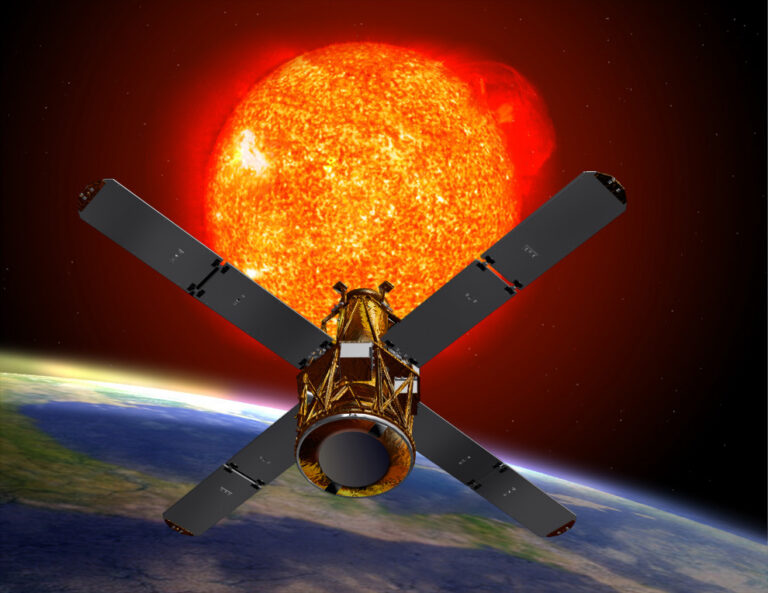

Voyager 2’s mission has been long and strenuous, to say the least. It’s traveled about 11 billion miles (17.7 billion kilometers) from Earth since it launched in 1977, and spent three decades cruising through space before finally reaching the outermost layer of our heliosphere — the massive bubble, created by the sun’s solar wind, that encompasses the Sun, its planets and regions far beyond their orbits.

Since it reached this remote region, called the heliosheath, in 2007, researchers have been patiently waiting for it to pass through the heliopause — the threshold that separates the heliosphere and interstellar space. And based on recent data, Voyager 2 is starting to make some headway.

Signals from space

In August, researchers noted that there was a five percent increase in the cosmic rays detected by the craft’s Cosmic Ray Subsystem, as well as its Low-Energy Particle instrument. Made up of mainly protons, electrons and atomic nuclei, cosmic rays blast through space at nearly the speed of light, and are thought to be ejected during powerful supernova explosions.

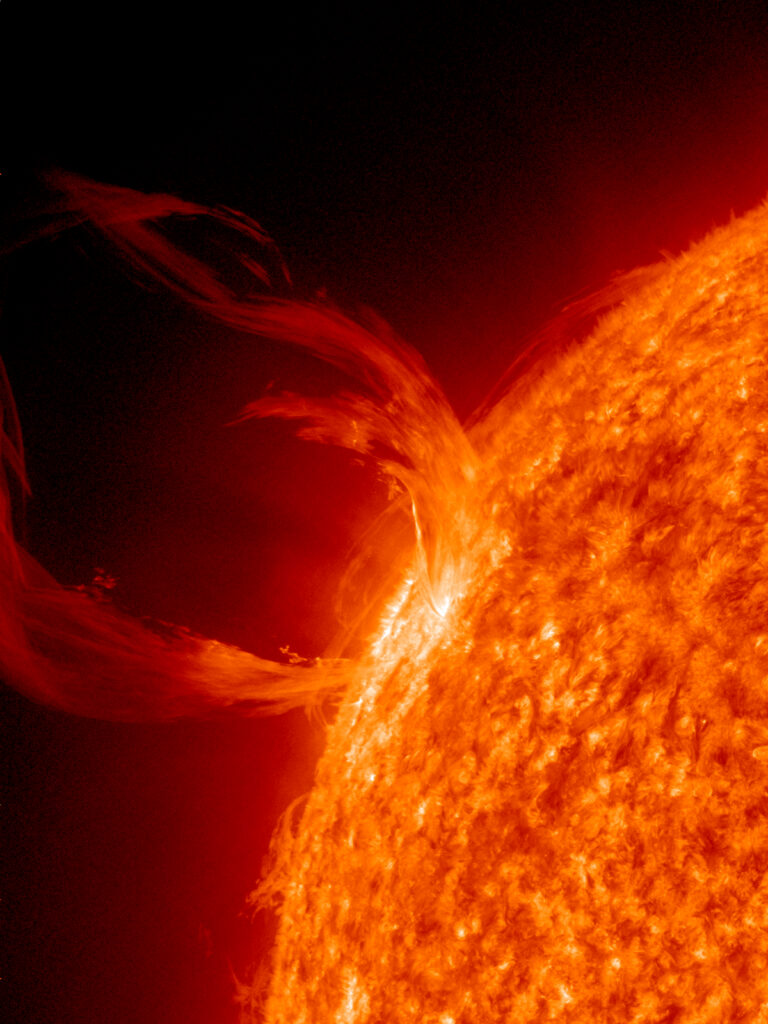

It’s believed that the heliosphere blocks a lot of these rays from reaching our solar system, but as you travel closer to the edge and the barrier starts to thin out, more cosmic rays become detectable. Voyager 2’s increased measurements suggest that it’s inching closer to the heliopause, and could soon enter the interstellar medium.

And if we’re going off of history, the craft could be crossing the threshold any day now. In 2012, Voyager 1 experienced a similar spike in cosmic rays about three months before it passed through the heliopause, becoming the first craft to invade interstellar space. It’s worth noting, though, that Voyager 1 entered the heliopause at a different location, which could cause discrepancies in cosmic ray measurements and time of entry. Voyager 2 is also lagging about six years behind its counterpart, so it will likely cross at a different point in the sun’s 11 year cycle. This cycle causes variations in solar flares, eruptions and winds, which makes the heliopause expand and contract.

This article originally appeared on discovermagazine.com.