Fade away

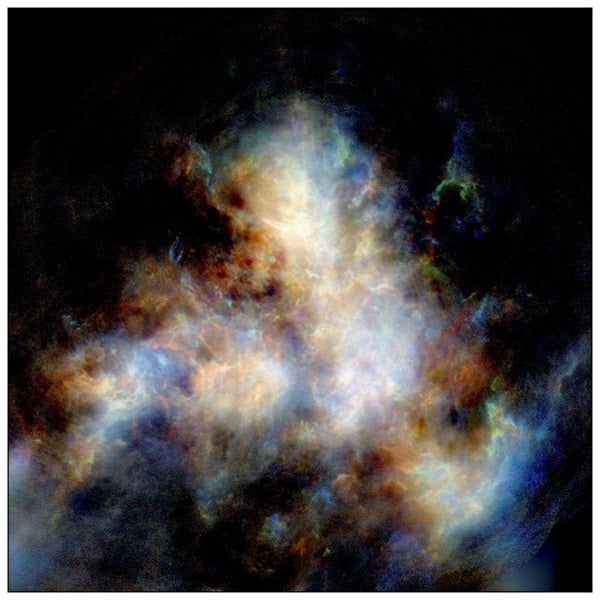

The results, published October 29 in Nature Astronomy, identify “a powerful outflow of hydrogen gas from the Small Magellanic Cloud,” said Naomi McClure-Griffiths of the Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics at The Australian National University (ANU), lead author of the paper, in a press release. The outflow, which astronomers believe may have formed between 25 million and 60 million years ago, stretches at least 6,500 light-years from the galaxy’s center. The team estimates the outflow contains about 107 solar masses of material, which amounts to about 3 percent of the galaxy’s total atomic gas. What’s more, the SMC is losing gas up to ten times faster than it is currently forming stars.

“The implication is the galaxy may eventually stop being able to form new stars if it loses all of its gas,” McClure-Griffiths said. In that case, she added, it will “gradually fade away into oblivion. It’s sort of a slow death for a galaxy if it loses all of its gas.”

Of course, the SMC’s story is already set to end in tragedy — ultimately, the tiny dwarf will be swallowed up, or “cannibalized,” by the Milky Way, all of its stars, gas, dust, and dark matter ending up as part of our own galaxy, with few traces of the dwarf left behind.

Galaxy-scale interactions

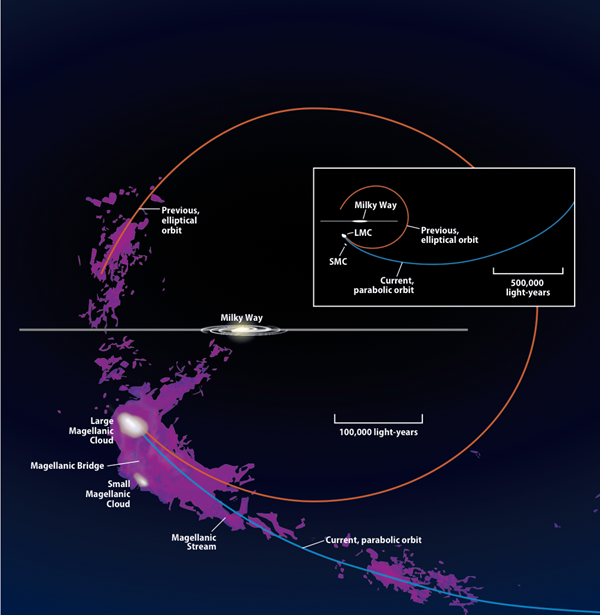

Several decades ago, astronomers first observed a “tail” of gas — mostly hydrogen — trailing the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, stretching more than 100° on the sky. Called the Magellanic Stream, the tail is believed to have resulted from gravitational interactions between the Milky Way and one or both dwarfs, though the exact cause is still debated and numerous factors likely contribute to its current length and shape. “The result [from this study] is also important because it provides a possible source of gas for the enormous Magellanic Stream that encircles the Milky Way,” McClure-Griffiths said.

With this first taste of the data quality available from ASKAP, the researchers are now ready to continue their work. “The telescope covered the entire SMC galaxy in a single shot and photographed its hydrogen gas with unprecedented detail,” said co-author David McConnell of CSIRO. “ASKAP will go on to make state-of-the-art pictures of hydrogen gas in our own Milky Way and the Magellanic Clouds, providing a full understanding of how this dwarf system is merging with our own galaxy and what this teaches us about the evolution of other galaxies.”