Key Takeaways:

The universe is full of surprises, and a colossal young star has been hiding a stellar one.

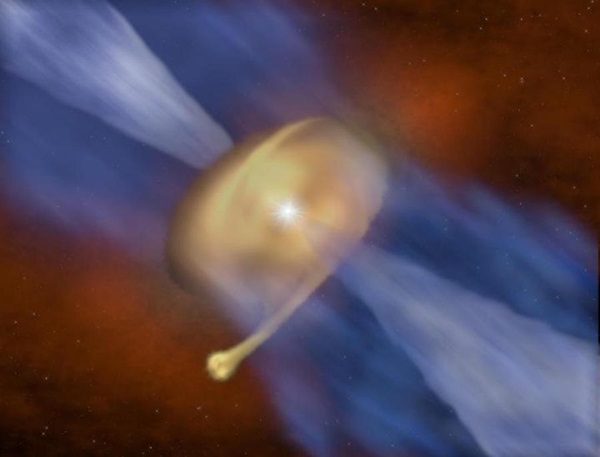

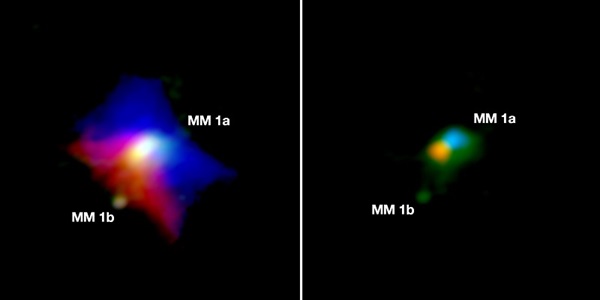

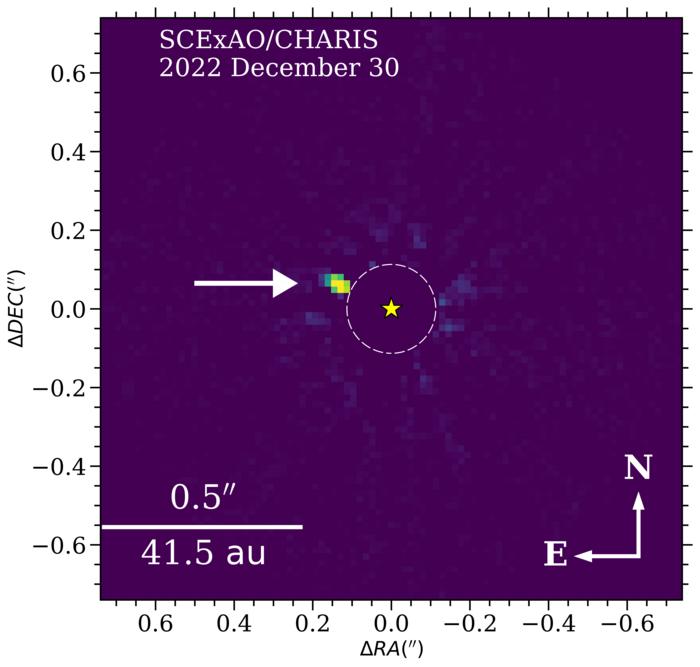

While observing infant star MM 1a, astronomers found that its massive disk was actually forming another star instead of planets. The much smaller companion, dubbed MM 1b, was detected just outside the behemoth star’s dusty disk, and could actually house a planet-forming disk of its own. The discovery of the new star, published on December 14 in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, marks one of the first times astronomers saw a star forming in the fragmented disk of another.

Stellar Siblings

Binary stars are pretty common in the universe, and it’s thought that they form the same way single stars do: from a massive cloud of dust and gas that collapses under its own gravity. If the molecular cloud is large enough, it can birth two similar-sized stars instead of one.

And since binary pairs are easily detectable, astronomers from the University of Leeds were rather surprised when they observed MM 1a. Homing in on the seemingly single star, they found an unexpected, much smaller companion star lurking in the outskirts of its dense disk — the region of dust and gas where planets typically form.

“In this case, the star and disk we have observed is so massive that, rather than witnessing a planet forming in the disk, we are seeing another star being born,” said John Ilee, a researcher at the University of Leeds and head of the study, in a news release.

To account for this stark contrast, the researchers think that MM 1b was actually born in a fragment of MM 1a’s disk. Due to its hefty mass, they believe that the disk wasn’t able to hold up against its own gravity, and ended up breaking off into fragments. One of those fragments housed enough dust and gas to create the low mass companion star, and possibly a planet-forming disk of its own.

Unfortunately, both of these stars and their prospective planets will soon meet a grim end. Despite lower mass stars like MM 1b having long lifespans, massive stars like MM 1a are pretty short-lived, and will probably destroy the whole system in a supernova in about a million years.

Fiery futures aside, the discovery marks one of the first times astronomers have seen a star forming from the fragmented disk of its companion. The finding could not only help researchers understand our universe’s strange stars systems, but also reminds us that there are plenty of stellar puzzles left to be solved.