Key Takeaways:

During a recent study of a distant GRB, researchers saw a “cocoon” of energy surrounding it. They believe that GRBs create these cocoons by transferring energy to them, and if they transfer too much, they become too weak to shine through the star and become visible. These findings, which could explain why powerful supernovae don’t always produce GBRs, were published on January 16 in the journal Nature.

A Super-Supernova

At the end of their lives, low mass stars like the Sun will quietly fade into darkness, while a higher mass stars will explode in a turbulent supernova. But enormous stars, which are more than 25 times the mass of the Sun, are thought to explode in a hypernova — which shines 10 times brighter than a supernova and leaves a black hole or neutron star in its wake.

It’s believed that GRBs emit almost exclusively from these hypernovae, yet astronomers have seen several that don’t produce GRBs at all. And up until recently, their absence has stumped researchers.

Capturing Cocoons

But back in December 2017, a team of researchers spotted a GRB shining from a galaxy 500 million light years away. They quickly traced the burst back to an early-stage hypernova. Here, the star had already collapsed into either a black hole or neutron star, but hadn’t ejected its outer layers and exploded yet. The GRB, which usually outshines the entire hypernova, was strangely dim. Because of this, they were able to home in on the event.

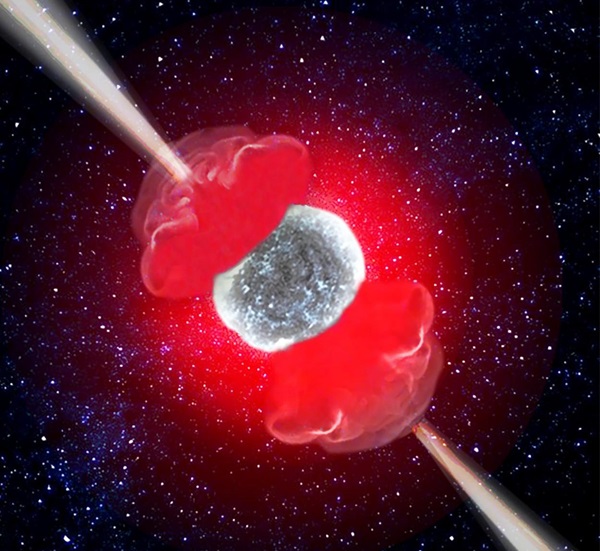

They observed the hypernova with the Gran Telescopio Canarias in Spain, and noticed something peculiar — a “cocoon” of high energy, rapidly expanding particles surrounding the GRB. The team used the telescope to measure the object’s chemical composition, and found that it emitted more energy than the GRB itself. This led researchers to believed that, as it traveled through the star, the GRB created the cocoon by transferring immense amounts of energy to it.

And if it had transferred too much, it wouldn’t have had enough energy to shine through the star’s outer layers and become visible. If these cocoons are created in all hypernovae, they could explain why some produce GRBs and some don’t.

“This work has allowed us to find the missing link between these two types of hypernova through the detection of an additional component: A sort of hot cocoon generated around the jet, as it propagates through the outer layers of the progenitor star,” said the study’s lead research, Luca Izzo of the Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia in Spain, in a news release.

Astronomers will need to carry out follow-up observations to confirm this theory, but if it holds up, it could forever change our understanding of stars’ turbulent deaths.